By Jesse Karjalainen

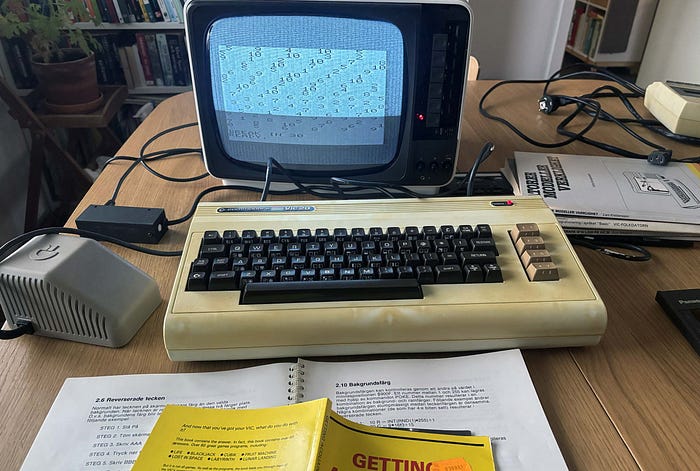

I was really keen to have a play with BASIC programming again, for old times' sake. The last time I "played" with BASIC programming on my VIC 20 was in 1984. According to my own memories, it was easy and fun. Now, some 40 years later, I cannot believe I was doing this at the age of 11.

Nothing about operating the VIC 20 is familiar. Technology has advanced so much in these past four decades that I had to resort to Google, Reddit and YouTube just to find out where to plug the power cable. Take a look at the power cable. Now compare it with the Video-Out cable. Which do you think is which?

Answer: the plug on the right is the power; Video-Out in on the left. For this reason, I very nearly plugged the power cable into the Video-Out socket. I am not sure if this would have fried the computer. Luckily, I spotted that the power went in from the side. They look incredibly similar.

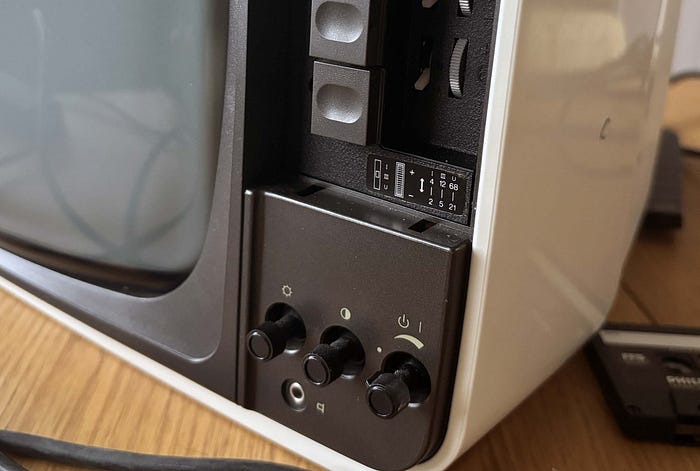

The good news was that the red power light lit up when I pressed the On button. Next, I put the Video-Out cable in the correct slot and put the opposite end (coaxial cable) into the TV. That was the easy bit. Then I had to do what we all did back in the analogue days — pick a channel and go through the endless motions of tuning it to find the computer signal on the TV.

I hope you are listening kids, there were no red/yellow/white RCA cables in the early days of home computing. Finding the computer signal required dialling the wheel up, up, up, up in search of a picture.

Usually, you got to the end and you heard clicking, that meant you had to dial back the other way down, down, down, down. Hopefully the lever on the right was set to the correct 1-of-3 positions — otherwise you had a whole lot more tuning on the wheel to.

Eventually … presto! We are finally up and running. Welcome back to 1981–1984.

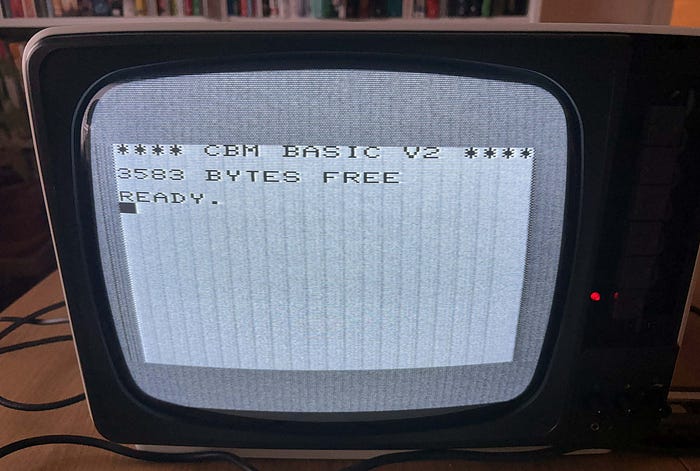

We get the computer screen reading:

***** CBM BASIC V2 *****

3583 BYTES FREE

READY.

The CBM bit stands for Commodore Business Machines. An hommage to IBM, perhaps?

And then it dawns on me: the sparsity of early-1980s home computing hits me in the face. No welcome screen. No desktop. No Start button. No icons. No programs. Nothing. This is the digital equivalent of a blank piece of paper.

Do with it what you will. Enter: BASIC programming.

Trying out BASIC

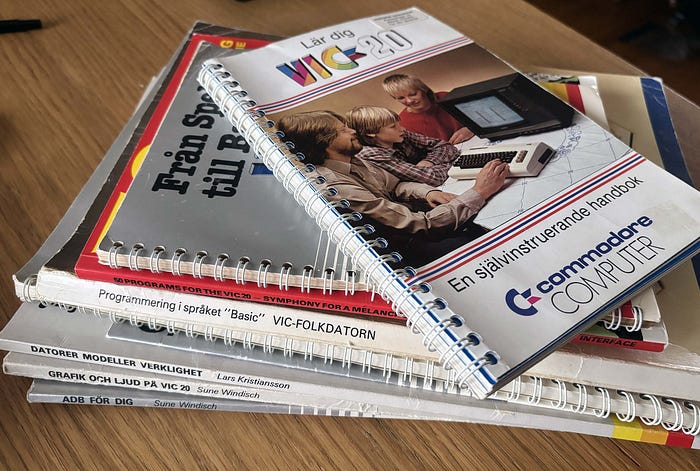

On my desk are a number of books about the VIC 20, from user manuals to introductions to basic. I pick up 'Getting acquainted with your VIC 20' by Tim Hartnell. It was published in the UK in 1982 and the copy I have has three price-tag stickers on it. These reveal an interesting history. The top, original sticker priced the books at 116 Swedish kronor. (Even at 2025 prices, 116 kronor is roughly 11 dollars. But this was four decades ago.) The second is a sale sticker, reduced to 75 kronor. The third sticker reads 10 kronor.

Anyway, the very first exercise in the book has just four lines of code. Perfect.

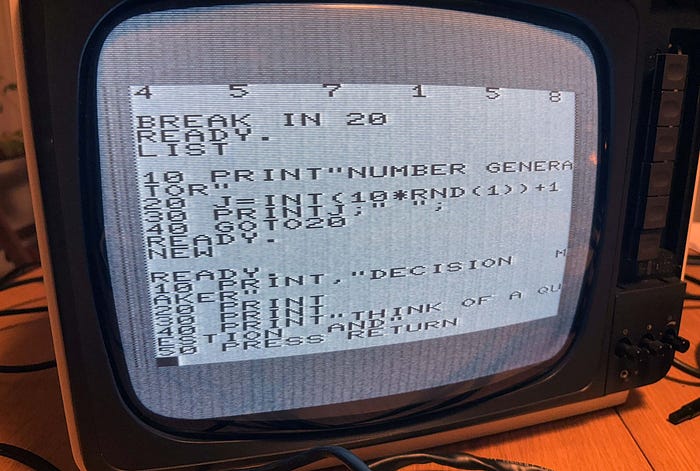

10 PRINT "NUMBER GENERATOR"

20 J=INTC10#RNDC1)2+1

30 PRINTJ:" " ;

40 GOT020

The first thing I notice is just how springy the keys are on the VIC 20. It's nothing like a typewriter — no resistance or stiffness. In fact, the keys feel like typing on a herd of gazelles all wearing Nike Airs. They spring up with a buoyancy that catches me by surprise .

Second, the clack-clack sound of the keyboard as I type is so satisfying. This is real haptics with non-emulated sound, all the way from the early 1980s. They say humans are wired for sounds and smells; they can transport us through time. It's happening folks.

I type in the code, making sure to press (RETURN) after each line. It strikes me as I type that everything is in uppercase. There is no lowercase lettering on the VIC 20, at least not from what I can tell.

The code I am writing is a random number generator done with four lines of code. Once completed, I type the first of two BASIC commands that remain etched in my brain all these years. RUN

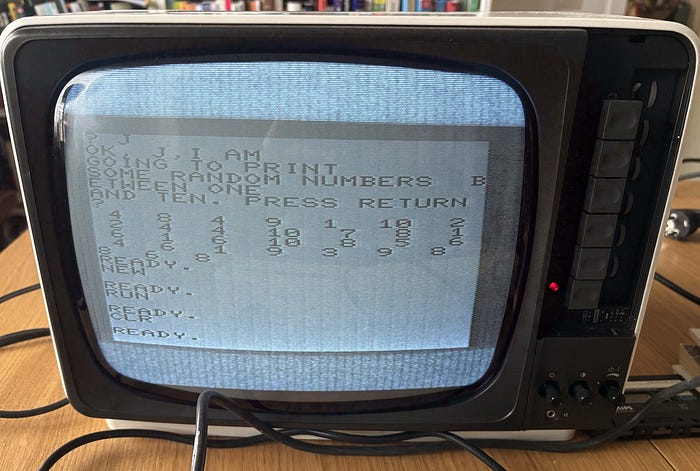

The screen is filled with constantly shifting random numbers. I suddenly have a problem: how do I stop a program once started?

I flip frantically through the manuals and the search online. It turns out the answer is to press the (RUN STOP) button on the left-hand side of the keyboard. The flow of numbers stops and I get a familiar prompt. READY.

But now what? That's as much BASIC that I remember. I have no idea how to get my code back or how to clear the screen.

I type NEW (I don't know why), nothing happens. I type RUN, nothing happens. I try CLR, nothing happens. It occurs to me that I have no idea how to bring back my original code. Have I even flushed it?

I search online and discover that NEW wipes the memory. So, I have to try something new. Let's try a different program. This one is a random number generator. I run it and stop it.

My knowledge of BASIC slowly starts to be retrieved from the vaults of deep storage. PRINT, GOTO, GOSUB, POKE and things like IF/THEN are making sense again, for the first time in 40 years. I finally figure out how to bring back my code — the LIST instruction — and my manual reminds me that (SHIFT)+(CLR HOME) clears the screen.

I tried LOAD and it gave me the classic response: PRESS PLAY ON TAPE.

When you step back and look at the BASIC interface of the VIC 20, you realise that the whole "desktop" is made up of a grid of 22x23 characters (not pixels). You can see in the photo above that …

ཆ PRINT"NUMBER GENERA'

… takes up the entire width of the screen. That's 506 characters for the entire visible workspace. It is a good reminder of what computing was like before the introduction of the Apple Plus and Windows 95.

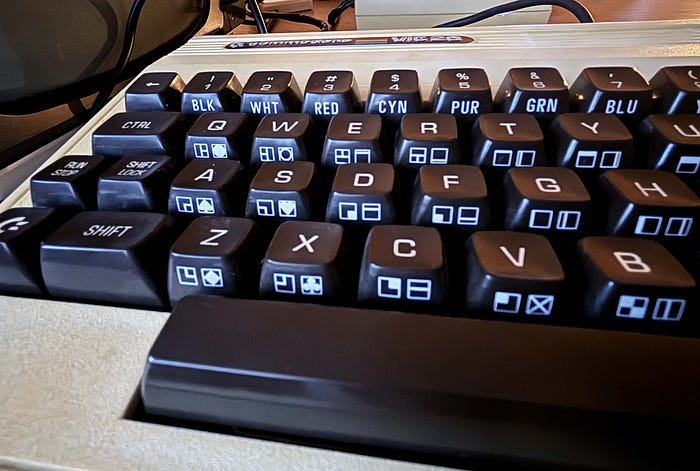

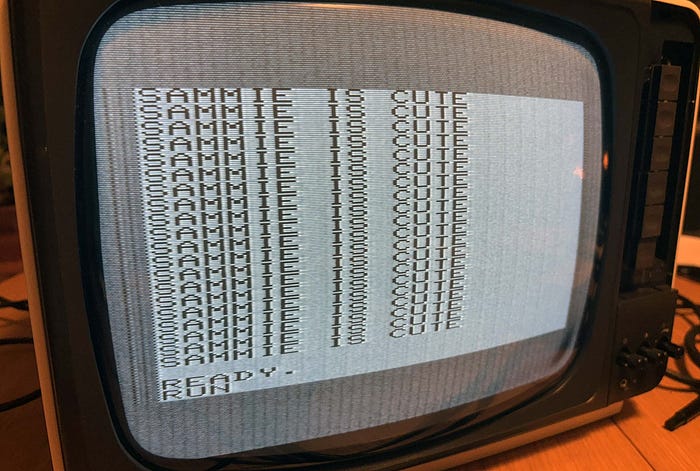

The amazing thing about the VIC 20 is that there are only uppercase letters. It's curious that there is no capacity for lowercase letters yet there are countless "graphic characters" built into the keyboard.

These are created using (SHIFT) for the left character on the key, or the Commodore key (nicknamed "chicken lips" by users) for the character on the right. It's interesting to think that you can literally type a ♥ symbol as a character rather than an image.

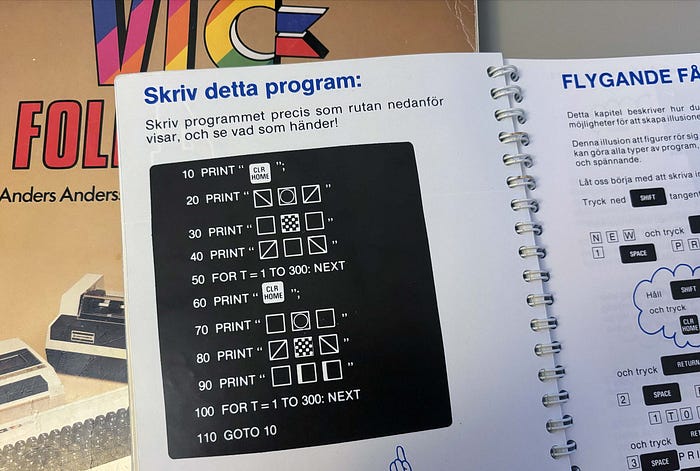

These graphic symbols start to make sense when I explore the animation section of my programming book. It's now that the advantages of BASIC become clearer. The introductory book takes me through using animation, colour and sound.

Still fun

I will admit that from the outset of this article, the skill of BASIC programming seemed impenetrable to my 50-year-old brain. HOW could this have been interesting as an 11-year-old, I wondered. The opening section of one book describes the VIC 20 in terms of, "The computer as an intelligent typewriter".

Despite having mere bytes of computing power, this experience has been a great reminder of how the VIC 20 charmed millions of kids around the world into exploring computing and programming.

Plugging everything in and switching it on to see nothing but a blank curser was a shock. My mind immediately thought: what can you actually DO with this thing?

It turns out that it is far easier to follow the manuals and start coding than it is to sit down and try to figure out how the computer worked. This wasn't the fun part. What was fun was typing in the code, seeing what happens and then — crucially — see what happens when you start tinkering with the code. In this way, unlike the Commodore 64, the VIC 20 really was a great introduction to coding and computers. And even better if our parents were baffled by it.

For kids who were curious and creative, getting into BASIC programming was both challenging and rewarding. Once you had the computer, it wasn't about buying games and expensive peripherals. It was about exploring what could be done with it.

Again, a reminder of context: in 1984 this was the most advanced technology available to ordinary households at the time. The fact that you could do things on the TV was mind-blowing and exciting.

BASIC in the 2020s

As a final experiment, I decided to introduce my 10-year-old daughter to the VIC 20 and see what she thought of it. Now, bear in mind that she think's Daddy and his CDs, records and old gadgets is dowdy, I was surprised that she showed more interest in this than when I taught her how to switch sides of the disc on the record player.

"I thought we could try some programming," I suggested.

"OK, Daddy. You know I do programming at school," she replied.

I knew that they have been working with Scratch programming on their iPads at school. This would come as a major disappointment to her as there would no graphic interface or cartoon cats. I decided to bring in some humour.

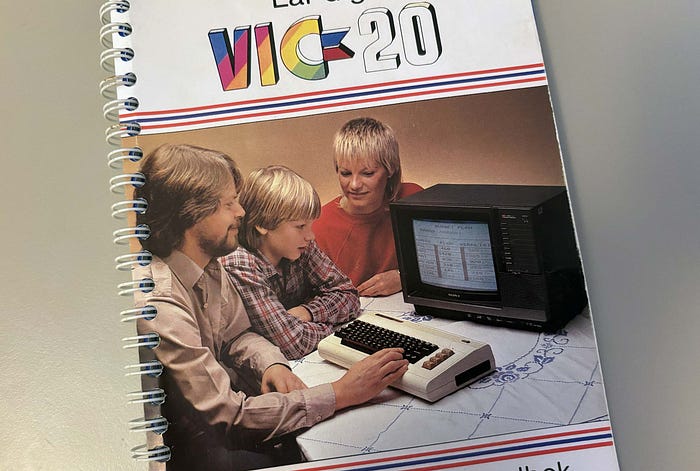

"Let's see if it is still as much fun today as it was for this family from the 1980s in this photo," I suggested, showing her the front cover of the VIC 20 manual on BASIC.

To my surprise, she said, "Can I type?" She was keen to try this funny looking machine. I got her to type in the Number Generator code. It kept having to remind here the importance of pressing the (RETURN) button after each line of code — and after each time she typed RUN.

Then we tried something simple again. This time to get the classic repeated lines of text. We decided to write something about our cat.

My daughter soon became confused about the TV. "I thought you said that was a TV, Daddy". I had to explain that the TV was a TV and that the VIC 20 was a computer.

"So can you still watch things on the TV?" she asked.

I nodded.

"Can we watch something on it then," said replied.

It was a logical response. From a 2020's perspective, the TV must have stuff **on** it that can be watched.

"It doesn't quite work like that anymore," I said. The last free-to-air television must have been switched off more than a decade ago.

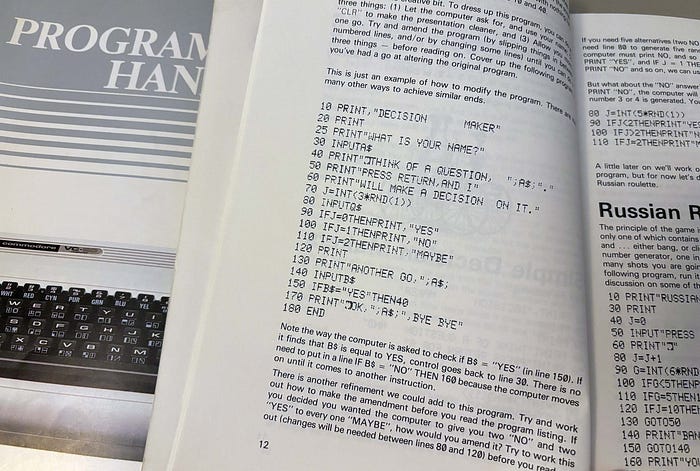

Next, we typed in a slightly more complicated program. This time, a "Decision Maker", in which when run you thought of a question to yourself and the program gave you a YES, NO or MAYBE response. Admittedly, I decided to type this in myself — I didn't think she would have the attention span to follow along with me. But she decided to stay and observe.

Then I got her to type RUN + (RETURN).

"We got an error, Daddy," she said.

"Not just that," I said, " we got a SYNTAX ERROR." The nostalgia was lost on her.

We fixed it and did a few rounds of the game.

Home computing

My overall impression was that she was actually quite interested in the computer. I can see how, if she didn't live in a world of iPads, YouTube, Netflix, phones etc, that she would probably have been as interested in the VIC 20 as I was back in the day at her exact same age. It turns out that the family photo on the manual was no exaggeration.

Firing up the old computer was also a reminder of what a powerful evolutionary step the VIC 20 and BASIC really were in the early 1980s. Every year, computers got better, more powerful and more interesting. And I was there from the start.

Those few years of BASIC programming on the VIC and later the C64 set me up with the fundamentals of coding, operating and instructing computers to do things. I can see now that the former computer had a lot more emphasis on coding — because there really wasn't a lot else to do on it. Saving to tape was indeed possible but the operating memory was still low. Nevertheless, it was fun trying to figure out how to make images, animations and simple games on the computer.

For this, the C64 was 1000 times better and more exciting. But the VIC set me up with the fundamentals of BASIC. It would turn out that we would be taught BASIC in school a few years later and the knowledge I gained from my first home computer, the humble VIC 20, certainly helped. But it was obsolete by the time I entered the world of work. Sniff.

See you next time.

Jesse is an author, illustrator and content creator currently based in Sweden. The Retro Tech show aims in chronological order to chart how the world went from the analogue age to the digital age. This is a personal memoir, starting in 1973, of every major technology I encountered in each year of my life.

None of the words in this series have been written by AI. This is 100% human sweat and toil. This content may not be used for AI training, so bots can stay away.

Find me and my content in my social circles:

Discover all my content here: https://jessebooks.gumroad.com/