Over the past few weeks, DeepSeek has been coming back from the dark. This time, to remind us once again how inefficient we are.

The models are not only 'frontier' in terms of raw performance but also a total redefinition of the Pareto frontier (performance per dollar), up to 60 times cheaper than some US counterparts.

And today, you'll learn what DeepSeek did differently to cause such a massive reduction in costs, called DeepSeek Sparse Attention, or DSA.

To do so, we'll review the intuitions behind how modern frontier models work in great detail, and how DeepSeek differs from all of them thanks to what I believe is the most significant algorithmic breakthrough of the year.

And all this leads to the next big token price-deflationary event, one that will only widen the gap that has become synonymous with AI:

Trillion-dollar investments for tiny revenues. That is, the so-called "AI bubble" might only get worse... and now also indebted.

This is based on reflections I post on TheWhiteBox, where I explain AI in first principles for those allergic to hype but hungry for knowledge. For investors, executives, and enthusiasts alike.

Join today for free.

Frontier results, dirt-cheap costs

As mentioned, DeepSeek has released newer versions of its flagship model, DeepSeek v3.2 Thinking and DeepSeek v3.2 Speciale, which score incredibly well compared to other top frontier models like Gemini 3 Pro, and at a much more cost-effective price.

The models are both reasoning models, aka Large Language Models (LLMs) that have been "post-trained" using RL. I've talked about this one too many times, so I'll cut to the chase:

- You first train an LLM by imitation, giving it a vast, Internet-scale dataset and telling it to imitate it to the comma. This bakes in knowledge into the model.

- And just like humans learn to solve math problems by trial and error rather than rote imitation, we use the same trial-and-error principle, known as Reinforcement Learning, on the resulting model from step 1, by 'reinforcing' good actions (i.e., the model tries a few things, and what works, we tell it "do more of that"), especially in areas like maths or coding.

The intuition is that trial-and-error learning helps "cultivate" reasoning, which is why the resulting model from step 2 is called a "reasoning model."

But the most striking thing is how outrageously cheap the model is to run. Just look at the results below, where it scores a very impressive 60% on the SWE-bench verified (a tier-1 coding benchmark).

But the key point is that, while it barely missed the top mark among Chinese Labs, it required literally $200 less than the model that outcompeted it by only 1%.

For reference, the highest absolute score is Claude 4.5 Opus with 74%, yet that model's run was 24 times more expensive per task than DeepSeek's, making the latter way more convenient on a performance-per-dollar basis.

It's hardly debatable; we have our best performance-per-cost model on the planet, and it's once again Chinese.

And to the surprise of no one, the API prices for the model are simply outrageous.

- $0.28 and $0.028 per million input tokens (non-cached and cached)

- $0.42 per million output tokens

Cached tokens are cheaper because we essentially fetch reusable data that was already precomputed. Think of this as responding to the same question by 10 users, buy reusing some of the compute used in the first response to respond faster and cheaper to the other nine.

For reference, this is how it compares to other frontier-level models in terms of prices:

Of course, the most immediate question here is: Why is this model so cheap?

And the answer is DeepSeek Sparse Attention, or DSA, their patented attention mechanism that may soon become the norm.

Overcoming Frontier AI's Biggest Issue

Have you ever wondered why, in AI, a single architecture, the Transformer, has been so pervasive for the best part of the last decade? And the answer is its expressiveness and the idea of global attention.

How AI models understand you.

In case you aren't aware, the AI industry is very dynamic in most things except for the most important one: the actual models.

You have a lot of variety in companies offering you AI products: OpenAI, Google, xAI, Anthropic, Mistral, and, of course, Chinese companies such as ByteDance Seed, DeepSeek, Alibaba Qwen, Minimax, or zAI.

But here's the thing, except for some details, they are all mostly building the same thing, a sparse Mixture-of-Experts autoregressive Transformer LLM.

That is a lot of buzzwords in a single sentence, so let's simplify. At the heart of every model your ears are familiar with is the Transformer block, the underlying architecture at the heart of most models.

In fact, modern LLMs are simply a concatenation of these blocks, one after the other, and when we say 'models are getting bigger' we mean one of two options: either we make each block larger, or we stack more of them sequentially (or both).

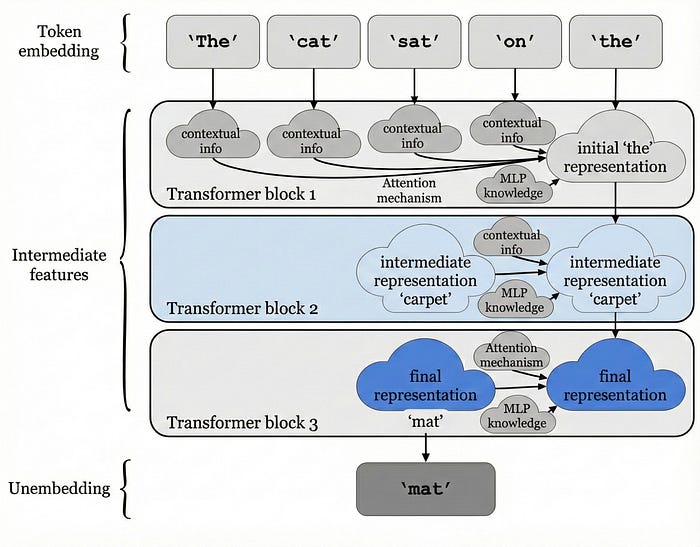

But what are these blocks? Intuitively, a Transformer-based LLM is just a concatenation of information gathering blocks, where each of these Transformer blocks does two things:

- Attention operation: Takes the user's sequence and applies the attention mechanism, where each word attends to all previous words in the sequence. This is sequence-level information gathering, meaning the model obtains information directly from the input text. This is done by a neural network layer known as the attention layer.

- Knowledge operation: This transformation adds model knowledge to each word. This is a channel-level information gathering, meaning the model gets information from its own knowledge. This is done in a neural network layer called the MLP layer.

Therefore, when we say models like ChatGPT take your input and predict the next word, what they are doing is taking the last word in the sequence and progressively adding information from the words in the sequence or from the model's internal knowledge over several Transformer blocks, where each block represents an update step.

At the end of this process, the last word has become a representation of the model's understanding of what should come next. Finally, we take that representation and find the word in the model's vocabulary that is most semantically similar to it.

I know all that made absolutely zero sense, but let's look at a simple example, and it will all make sense then.

Who is Luka Dončić?

Say you give the model the sequence "Luka Dončić plays the game of…". Of course, the model has to predict "basketball".

But how?

- Attention will make "game" pay attention to "Luka Dončić", so "game" now encodes new information provided by the latter. The game we are looking for is related to this Luka guy.

- In parallel, the word "plays" also attends to "Luka Dončić," helping the model understand that this "Luka Dončić" guy is a player of a sport.

- And once the word "game" pays attention to the word "plays", it will also learn not only that we are talking about a human called "Luka Dončić" but also that, as the word "plays" is included in the sequence, this means this "Luka Dončić" guy must be a sports player.

As you can see, by having words share information, the model builds an understanding of the overall sequence. However, no reference to the word 'basketball' appears in the sequence, so how does the model know what to predict?

Think about this from a human perspective: can you predict the next word is 'basketball' if you don't know who Luka is? No.

This leads us to the following realization: the model can use attention to infer that this "Luka Dončić" guy is a sports player, but unless it knows who Luka is, it can't predict "basketball."

Here's where the second operation in the Transformer block comes in. This is harder to visualize, but the point is that at some point in the past, during its training (or several of them), the model was exposed to data in which Luka is clearly described as a basketball player. And by being trained to imitate that data, the model has indirectly learn who Luka is, and that the dude plays basketball.

Therefore, the second operation, the MLP layers, allows the model to add the missing contextual information from its own knowledge.

So, in a nutshell, the attention part helps the model understand what the user wants, and the MLPs provide the necessary knowledge to make an accurate prediction.

Fascinatingly, we can visualize this process using things like linear probes and observe how the model's internal representation of the next word slowly becomes the word "basketball", and, by the end of the process, the word predicted as most likely is, in fact, basketball, or 'mat', as shown in the example below:

As you may have guessed from your interactions with ChatGPT, this works pretty well, but has some significant connotations.

'Attention to literally everything' is all you need

A standard Transformer model has what we know as a global attention inductive bias. I know the previous sentence was another jargon-rigamarole, so let's unpack it a bit.

AIs learn mostly by induction, going from the specific to the general. In other words, they learn something by seeing it a lot (e.g., "If every single apple I've seen in my lifetime falls from a tree downward, it's safe to say that the next time I see one, it won't levitate").

To learn from induction, one has to make some assumptions from the data; otherwise, we can't learn. Using the previous example, if the model never jumps to conclusions, it can see trillions of apples falling, and still never infer the next one will fall too.

Therefore, an AI researcher's job is to choose the right induction biases (aka assumptions) for learning.

A Transformer's most important inductive bias is global attention; the attention process we described above is done from the last word in the sequence to all previous words, without distinction.

Even though some words matter more than others (in the Luka Dončić example, "game" and "plays" share more information than "the"), the model doesn't care and treats them all equally. This is crucial to understand what DeepSeek is doing differently.

Funnily enough, in the spirit of confusion, what I just said is both right and wrong, in that the attention mechanism does decide what words should be attended to more than others… but the key is that it does not preemptively discard any.

In other words, it's a very compute-intensive operation because every single word must attend to every other word that precedes it.

Even if the word is just "um" that doens't provide any meaningful information beyond hesitation, the attention update will ignore it but it will still pay attention to it "just in case."

Importantly, this is one of the big reasons, if not the main one, as to why we can't make the model's context windows larger; the number of attention operations scales quadratically to sequence length, meaning that doubling the sequence length quadruples the number of operations, tripling implies a nine-fold increase… You get the gist.

Countless things have been proposed over the years to make attention cheaper, but all have mostly failed.

Finally, however, DeepSeek seems to have nailed it in what could be the most relevant algorithmic breakthrough of the year. Here's how.

Not all tokens are made equal.

When we humans read a piece of text, even if we aren't consciously aware of it, our brain skips a considerable portion of the words, either because it immediately recognizes they are irrelevant, or can literally predict what that part says and jump it.

Instead, our "smartest" AIs scrutinize every single word, as if we asked ourselves, for every word we read, whether that word is relevant or not for what is coming next.

Painfully inefficient, right?

And yes, even if you aren't aware, your brain is performing an attention mechanism, one that is very similar to the one we are describing… but does so orders of magnitude more efficiently.

I would only add that our brain generally does bidirectional attention, not autoregressive, but I digress.

So, what does DeepSeek propose? Well, doing just that, teaching the model to recognize word importance without having to attend to each word.

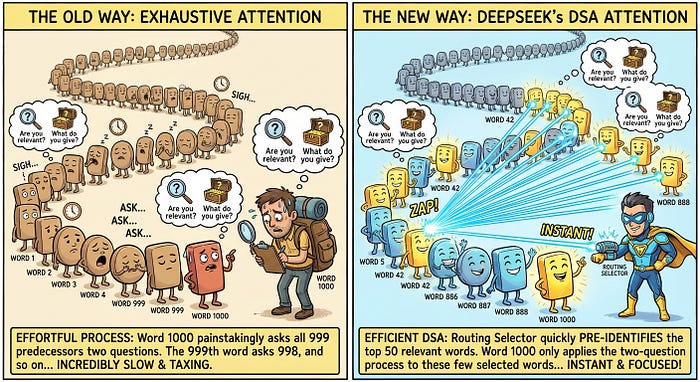

To understand how, we don't have to get into the deep details on how attention is done. For today, you just need to know that this 'attention process' we have gone through today is basically every word making the following two questions to all other words in the sequence:

- Are you relevant to me?

- What are you giving back to me if I attend to you?

Recall that the attention mechanism is nothing but an information gathering process between words, and that both of these "questions" have a computational cost.

In the first question, the ones that are identified as relevant receive a higher "attention score," which ranks every preceding word on importance.

Then we use this score to perform the word update, meaning each word is updated with information from all preceding words, weighted by their attention scores (i.e., if a word has a high attention score, it will provide more information). That is the effect of the second question.

But the real taxing thing here, and one that is clearly inefficient, is that we are forced to do this two-question process for every preceding word; the model isn't opinionated about what words matter.

For example, if we have a 1,000-word sequence, the 1,000th word makes this question 999 times. The 999th word makes it 998 times, and so on.

So, what if we could find a way so that the 1,000th word preidentifies the, say, 50 words it has to attend to maximize information gain and performs the two-question process described above 50 times instead of 1,000?

And in a nutshell, this is precisely what DeepSeek v3.2's DSA attention mechanism does.

But how?

The process has two steps: a token selector and the attention process itself. This token selector behaves like an additional first question, so that the process is now like this:

- What words do I think are relevant?

- And then, on the selected words, ask the two questions described above.

At first, this seems like it'll have the opposite effect: more computational requirements, since each word has one more question to ask.

However, the crucial idea is that the cost of asking this first question and thus filtering the number of words that flow to the following two questions is much lower than naively asking the first two questions to all words.

This is intuitive to see; if every word attends to a much smaller number of preceding words, the overall computational requirements are much, much smaller.

Think of this as having all the words you need to ask in a long line, and instead of asking them one by one, first perform a quick analysis of the most promising candidates and ask only those. Yes, you are risking not questioning relevant words you might miss, but the point is that these top words combined offer enough information to ignore the rest.

Brilliantly intuitive, right?

Before we move to the final section, I've added a brief technical section that explains why this is cheaper in more detail, but it assumes some knowledge of how Transformers work. If you're not interested, you can proceed to the final section. So, now what?

Technical explanation (not required to continue reading)

The standard attention mechanism involves four steps:

- For each word, we project its embedding into three smaller vectors: the query, the key, and the value. The query represents 'what the word is looking for', the key explains 'why this word might be relevant to attend to', and the value represents 'what information this word gives to other words if attended to'.

- We compute the attention score of one word with all the preceding ones by multiplying its query by the keys of all other words.

- We apply a softmax normalization to the attention scores, which transforms the unnormalized scores into a probability distribution (i.e., each word in the sequence is ranked by its attention score).

- We perform the attention update, where the word gets added the value projections of all preceding words weighted by the normalized attention scores (it's literally a weighted sum of word meanings).

This four-step process is repeated multiple times per word, with that number equal to the number of attention heads (the idea is that by breaking the process into several groups, each attention head specializes in identifying different subtleties).

But why is DSA cheaper?

Simplifying the process, step 1 has a cost complexity of O(3*d_model²*L), because we perform, for every word in sequence L, three matrix projections of size (L, d_model)x(d_model, d_out).

This means the computational cost of this step is quadratic in the model's dimension and linear in the sequence length L, so this first step is heavily influenced by the hidden dimension (d_model).

But where's d_out in all this? We usually define 'd_out' as d_model/number of heads, so it's effecitvely d_model² once we consider the computional cost of all attention heads combined. We are of course ignoring the batch dimension (i.e., we are assuming batch size = 1).

On the other hand, steps 2–4 have a cost complexity of O(L²*d_head*n_heads), meaning their cost depends primarily on the sequence length, making a total cost O(L²*d + d²*L) ~ O(L²) for long sequences. Thus, these steps are highly affected (computationally speaking) by increases in sequence length.

So what effect does the token selector have? The selector adds an extra step, but it does so in a computationally cheap way: with a small number of heads and a much smaller projection (d_selector <<<< d_model) for all tokens in the sequence L.

We are adding overhead, yes, but here's the thing: for the calculations in steps 2 to 4, the projections and the softmax computation, we are no longer constrained by sequence length as the determining factor in our cost curve and instead constrained by 'k', where 'k' is the number of tokens selected by the selector.

The cost complexity is now O(L * k * d_head * n_heads), switching L² by L*k where k<<<<<L.

Therefore, while this process does not save much compute in the projection step (which is more heavily affected by the hidden dimension size), it saves a lot of compute in the softmax-weighted sum, whose cost complexity is mostly governed by the sequence length L.

This was intuitive in itself, simply by understanding what was going on (we are applying attention to a much smaller subset of words). Still, it's also nice to see the cost complexities and how the extra step actually helps.

And Now… What?

So, what to take away from all this? The shortest answer is one word: pain.

We are about to see the next big token prices deflation event by companies that weren't even close to making money already, and less so now.

This model is outrageously cheaper than other models, especially US ones, for just a marginal improvement from the latter group.

You and I both know this is totally unjustifiable, and US Labs, while they'll probably milk the current token prices as much as they can, will be forced to cut prices eventually and several times their current value.

This is relevant, considering we haven't seen substantial price reductions in over a year.

If you're a Westerner reading this, you should not underestimate the importance of Chinese Labs' contributions to improve open-source models and, above all, force Western frontier Labs to cut prices.

Even if you don't use DeepSeek a single day in your life, which is totally fine (and you should be very wary of consuming Chinese applications), you are still reaping the benefits of the release simply because it's forcing US Labs to compete.

And that in itself is a victory.

Of course, we also both know why this is happening. This is just China's way of retaliating against GPU export restrictions. If the US doesn't want China to compete, China will make sure US Labs can't make money either.

The truth is, it's working because no US Lab is remotely close to turning a profit. In fact, they are hemorrhaging money. Nonetheless, OpenAI projects a ~$50 billion cash burn in 2028 alone.

This is unsustainable with equity financing rounds; it's simply too much money. For that reason, in 2026, I believe we will see an explosion in the corporate bond market, one that may hide surprises, such as higher yields on sovereign bonds, as bond investors flock to the more attractive yields offered by Big Tech bond issuances, which have already started.

Of course, I could very well be wrong, but where I'm quite sure I'm not mistaken is that 2026 is going to see the start of AI's debt financing phase, the phase where most money will be raised in the form of debt.

And you know what's common across all economic crashes in history, right? Yes, the unequivocal role of unpaid debt.

But let's leave this conversation for another day. In the meantime, we can say it: China is once again telling us, "To the peoples of the Western world, your models are too damn expensive."

If you enjoyed the article, I share similar thoughts in a more comprehensive and simplified manner on my LinkedIn (don't worry, no hyperbole there either). As a reminder, you can also subscribe to my newsletter.