All you have is:

- A flashlight (your sensor)

- A notepad (your memory)

Your job is to:

- Figure out where you are (Localization).

- Draw a map (Mapping)

You have to do both at the same time — because you can't localize without a map, and you can't build a map without knowing where you are.

This is SLAM: "Simultaneous Localization and Mapping" .

We're basically trying to solve the classic 🐔🥚 problem: "Which comes first — knowing where you are or building the map?" SLAM says: why not both, together?

Graph SLAM:

One way to solve the SLAM problem is Graph SLAM. It is like a giant puzzle make of constraints.

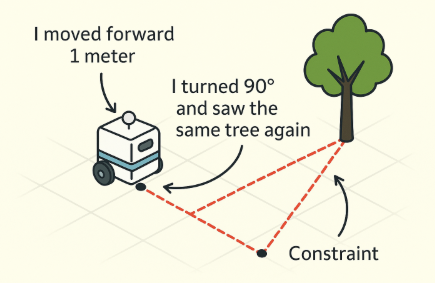

A constraint is just a piece of information about how things relate to each other. For example, it tells us:

" I moved forward 1 meter."

"I turned and saw the same landmark again."

"This position is 5 meters away from that one"

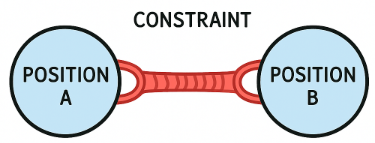

A constraint like a rubber band that pulls two positions toward a certain relationship. It doesn't say exactly where things are — it just says how far apart they should be, or how they're connected.

Overall, in Graph SLAM, the robot is trying to answer:

"Where have I been?"

"Where are the landmarks?"

…based only on the relative movement and noisy sensor data.

Dive deep into the technical formula:

While the robot is walking around, it collected many clues. Then it put all those clues together and figure out the best guess of:

- Where the robot is at each step (poses).

- Where each landmark is.

This is where Ω⋅μ = ξ comes in.

Where:

Ω(Omega) is the information matrixμis the vector of unknowns (robot poses, landmarks, etc.)ξ(xi) is the information vector

What Do These Symbols Mean (Intuitively)?

👉 Think of μ as a list of positions:

- Robot at time 0: x₀

- Robot at time 1: x₁

- Robot at time 2: x₂

- Landmark 1: l₁

- Landmark 2: l₂ …and so on.

This is your map + trajectory — the thing you're trying to figure out!

👉Think of Ω (Omega) as how strongly you believe in the clues.

- It's like a giant trust web.

- Each time the robot says "I moved 5m," it ties two positions (say x₀ and x₁) together.

- These become connections in the matrix — like rubber bands with different strengths.

So Omega tells you:

- Which things are connected (via constraints)

- How strong those connections are (based on measurement certainty)

It's called the information matrix because it reflects how much "information" (i.e., certainty) you have.

👉Think of ξ (xi) as all the clues you collected.

- It stores the actual measurements you've made (like "x₁ is 5 meters from x₀").

- It's like your notepad of clues from the world.

👉 In summary Ω⋅μ = ξ can be interpreted as: "How strongly positions are connected" × "The positions themselves" = "What we actually measured."

How do we solve Ω⋅μ = ξ?

The robot builds the matrix (Ω and ξ) as it walks around .…..

Every time the robot moves or makes an observation, it adds a new piece of information — like a clue in a detective notebook.

That clue gets translated into:

- A few numbers added to the matrix Ω (how things are connected)

- And some values added to the vector ξ (actual measurements)

Eventually, it build the Ω and ξ, then we solve the equation to get μ that gives us the best guess of where everything is.

Let's take a look of a real world example:

Our robot moves along a hallway and makes two movements:

- It starts at unknown position x0

- x0 → x1 : moves 1 meter forward to x1

- From x1, it sees landmark l1 is 2 meters to the right

- x1 → x2: moves 1 meter forward to x2

- From x2, it sees landmark l2 is 1 meter to the right

We'll estimate the most likely positions for x0,x1,x2,l1, l2 using SLAM.

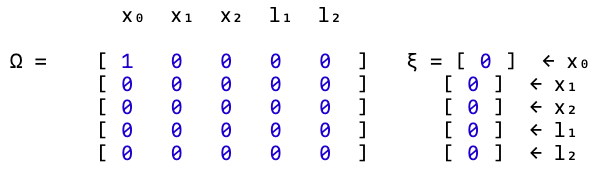

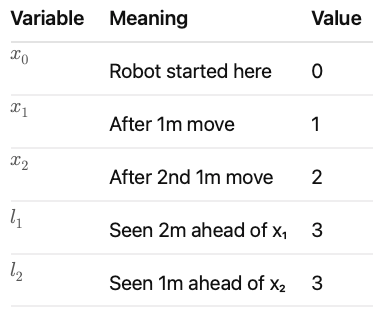

Step 1: Define the Variables

we are solving for:

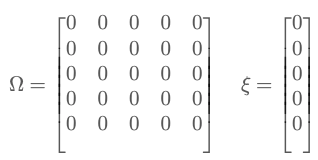

So we need:

- A 5×5 matrix (Ω)

- A 5×1 vector (ξ)

Step 2: Initialize Ω and ξ with zeros

Step 3: Anchor the first position x_0 = 0

Step 4: Motion constraints

As the robot moves and senses landmarks, it gathers relative measurements. Each constraint is a relative observation. It gaves us a "Rubber Band" between positions.

a ) When:

- x0 → x1 : moves 1 meter forward to x1

x1 — x0 = 1, meaning:

"x₁ is 1 meter ahead of x₀"

This becomes a constraint between two variables (x₀ and x₁). We want to add this info into our system (Ω, ξ) so the final solution for mu = [x0, x1, …] respects this relationship.

We update Ω: Ω[0, 0] += 1 and Ω[1, 1] += 1

This adds weight (trust) to both variables involved.

- You're saying: "I now have one piece of info involving x₀ and one involving x₁."

- So you increase their diagonal values (kind of like boosting their confidence).

Think of it as:

"We know something about x₀ and x₁ now, so let's make their positions matter more."

Next, we update Ω: Ω[0, 1] -= 1 and Ω[1, 0] -= 1

This encodes the relationship between x₀ and x₁.

- It reflects that x₀ and x₁ are not independent — they are tied together.

- The off-diagonal terms form a "rubber band" pulling their values toward each other with a fixed offset of 1.

Think of this as saying:

"The difference between x₀ and x₁ should be 1."

If x₀ goes too far from x₁, this rubber band pulls them back.

Lastly, we update ξ: ξ[0] += -1, ξ[1] += 1

This encodes the actual measurement:

x1 — x0 = 1

Rewriting:

x0 — x1 = -1

- This is where the value of the measurement is stored.

- ξ acts like a "notepad" where the robot writes down what it actually observed.

The updates mean:

"Hey x₀, adjust your belief downward by 1"

"Hey x₁, adjust your belief upward by 1"

Together, this encodes the idea that: x₁ is 1 more than x₀.

🤔You may get confused here that after the update… doesn't the difference between x0 and x1 become 2, instead of 1.

Short Answer: No — it still enforces x1 — x0 = 1.

When building Ω and ξ, we translate it into a least squares problem, which minimizes: (x1 — x0–1)², which is same as (x0 — x1 — (-1))² → x0 — x1 + 1

The vector part (ξ) comes from taking the derivative of this squared error function with respect to x₀ and x₁ — that's where: xi[0] += -1, xi[1] += +1 comes from.

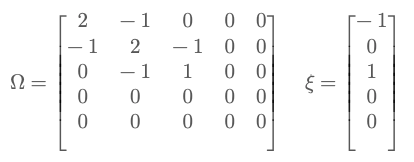

b) Similarly, when:

x1 → x2: moves 1 meter forward to x2

Update:

- Ω[1,1] += 1, Ω[2,2] += 1

- Ω[1,2] -= 1, Ω[2,1] -= 1

- ξ[1] += -1, ξ[2] += 1

Now, we have:

Step 5: Landmark observations

a) From x1, robot sees l1 = x1 + 2

Rewritten as: l1 — x1 = 2

Update:

- Ω[1,1] += 1, Ω[3,3] += 1

- Ω[1,3] -= 1, Ω[3,1] -= 1

- ξ[1] += -2, ξ[3] += 2

b) From x2, robot sees l2 = x2 + 1

Rewritten as: l2 — x2 = 1

Update:

- Ω[2,2] += 1, Ω[4,4] += 1

- Ω[2,4] -= 1, Ω[4,2] -= 1

- ξ[2] += -1, ξ[4] += 1

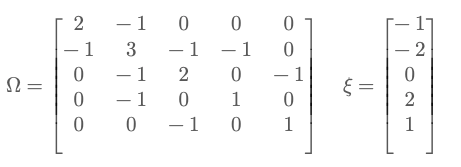

Now, we finally have:

Step 6: Solve Ω⋅μ = ξ

import numpy as np

Omega = np.array([

[2, -1, 0, 0, 0],

[-1, 3, -1, -1, 0],

[0, -1, 2, 0, -1],

[0, -1, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, -1, 0, 1]

])

xi = np.array([-1, -2, 0, 2, 1])

mu = np.linalg.solve(Omega, xi)

print(mu)Output:

[0. 1. 2. 3. 3.]

Final Interpretation:

📘 Also check out my related articles about AI in Robotics: - [Bayes' Rule in Robot Localization] - [SLAM: How Lost Robots Build a Map] - [Kalman Filter — Combining Messy Sensors with Math] - [Particle Filters: An Intuitive Guide to Robot Localization] - [Where AI Robots Take Us, Practically and Philosophically]