Gale-force winds ripped across the island and knocked me off-balance. Snow and shards of frozen rain felt like buckshot through layers of protective clothing and stung the uncovered flesh between my mask and sunglasses. Visibility was poor and got worse by the minute.

We stood (or tried to) on Detaille Island — a desolate speck of land below the Antarctic Circle at 66°52′ South, and further south than many visitors to Antarctica ever reach. After a sporty ride across roiling seas in our inflatable Zodiac boat, we were deposited in knee-deep water on a rocky shore. From there we climbed a precarious trail of icy boulders to reach some semblance of terra firma. Emerging above the boulders, we were exposed to the full force of the wind and each step forward became a tiny victory.

The expedition guides had warned us that the Zodiac journey, shore landing, and conditions on the island would be rough, and I now understood their definition of rough. This was our expedition leader's first visit to the island in 20 years, and many of the guides had never been here at all. Crossing the Antarctic Circle and setting foot on Detaille was special for all of us.

By the late afternoon, winds reached 65 knots (75mph) — equivalent to a Category 2 hurricane. Another Zodiac full of passengers that attempted to land after us aborted en-route, and because the tiny craft couldn't land on shore, or return to the mothership, they found themselves in a bizarre Antarctic limbo and had to hide in the lee of a nearby iceberg until conditions improved.

An Australian man at the bow of this Zodiac was pummeled by waves and drenched with frigid seawater for most of the afternoon. His boat never reached Detaille Island, but he later told me that trying to get there was one of the greatest experiences of his life.

Meanwhile, I was fighting for every step. I glanced around the rocky landscape and braced myself against the blasting wind. Someone's wool hat raced toward me across the snow, and I sidestepped to catch it before it blew out to sea behind me.

Looking around this seemingly inhospitable place, I felt a true taste of Antarctica. Not the peaceful harbors, blue skies, and picturesque wildlife on the marketing materials, but the raw, dangerous, painful power of the most wild and most remote place on earth. This was the Antarctica I came to see, and it was ironic that I could barely see anything at all.

British Base W

As conditions worsened, I undertook a time-honored tradition in which humans have participated for time immemorial — getting the hell out of the weather.

A building stood nearby, situated on a rocky foundation and covered by gray wooden planks, weather-beaten by 70 years of harsh polar conditions. The windows were boarded up, either to keep the weather out or the ghosts in. In the blizzard, the gray building was a monochromatic and haunting site, but I was less interested in sightseeing and eager to find my way inside.

The building was Base W of the British Antarctic Survey — an abandoned research station that operated continuously for three years in the 1950s before its hasty evacuation. Base W was the home for surveys, geological, and meteorological research, and countless contributions to the International Geophysical Year in 1957.

Built as a sanctuary to endure the very same conditions that presently ravaged Detaille Island, I was anxious to climb the ladder and test the old hut's capability as a shelter.

I stepped into a time capsule; pitch black and eerily quiet. When the base was evacuated, the men took only their most valued possessions. Everything else was left behind and has been completely undisturbed since April 1, 1959.

I walked slowly down the hall away from the door and the screaming wind. The wooden floor creaked under the weight of my boots. It was like investigating a haunted house, room by room, with only the light of my headlamp to illuminate the way. Unlike the derelict and crumbling ruins of another British Antarctic base I had recently visited (the ruins of Base B on Deception Island), Base W was completely intact.

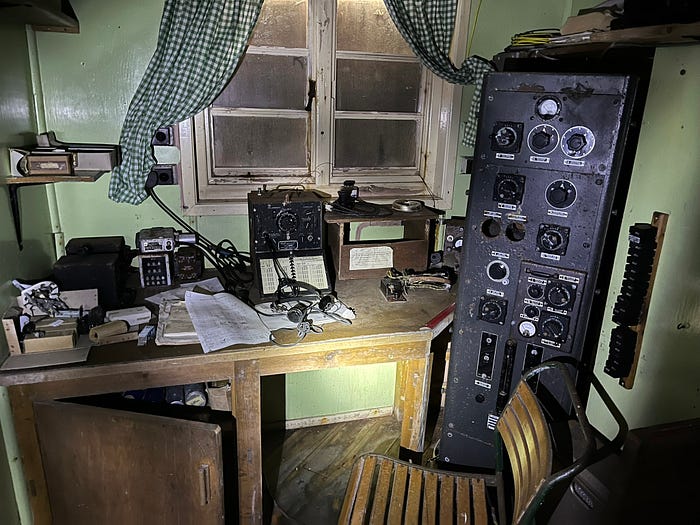

I crept further down the hall and peeked into the radio room and the meteorological office, used for geological and meteorological experiments and research. Next was the toilet and washroom, as well as the lounge and an office.

At the end of the hall was the kitchen and dining room, marked by a large table and shelves of food and canned provisions, including oats, custard powder, processed cheese, Heinz mayonnaise, and empty bottles of gin and whisky. On the dining table was an open guest book, and after my hand warmed up, I gladly signed it. Beyond the dining room was the bunk-room, and several beds were arranged in neat rows.

Base W is an eerie time-capsule stocked full of items patiently awaiting owners who will never return. It was easy to imagine the place as a pleasant refuge where science was discussed and experiments were conducted. The dining room table was likely host to many stories and laughter, birthdays and milestones, as well as some loneliness and sorrow.

Other artifacts scattered around the building included jackets and long-johns hung upon racks, skis, survey books, maps, navigational tools, astronomical logs, and a pair of boots waiting patiently beneath a bed.

Near the main building was an anemometer tower for measuring windspeed, a sledging workshop, generator shed, radio masts, an emergency storage building, and a kennel for the sled dogs.

The men who inhabited Base W must have been a special breed. An adventurous spirit would have been required, as well as absolute dedication to their craft. These scientists contributed to the International Geophysical Year (IGY) in 1957 — a cooperative program to study the earth and its environment, chosen for 1957 to coincide with the maximum sunspot cycle. Several British bases, including Port Lockroy, Horseshoe Island, and Detaille Island, were key monitoring sites during the IGY, and Detaille was one of two bases that contributed critical meteorological data.

Evacuation

In 1959, the scientists stationed at Base W learned that heavy sea ice prevented their supply ship, the RRS Biscoe, from approaching within 31 miles (50km) of Detaille Island, despite the help from two U.S. icebreakers. The base didn't have enough coal for another winter and the ship was unable to unload provisions from the ice edge. The scientists knew that the unstable ice and inability of the Biscoe to reach them would leave them with insufficient food to survive the winter.

On April 1, 1959, the men took matters into their own hands and closed up the base. They packed only their most valuable gear, and used dog teams to sledge more than 30 miles across the ice to reach the Biscoe near Horseshoe Island Hut (Base Y), where they found safety.

As they loaded the dogs onto the ship, a husky named Steve slipped his harness and escaped across the ice. The men wanted to go after him but with temperatures dropping and new ice forming, they were heartbroken and had to abandon Steve to his fate. They watched the dog disappear over the horizon as the Biscoe got underway.

Almost three months later, Steve once again appeared at Horseshoe Island, not just fit and healthy, but 20 pounds above his normal weight. It was theorized that he must have found his way 30 miles back to Base W where he gorged himself on the seal pile from which the dogs had been fed, and three months later, he made his third 30-mile journey back to Horseshoe Island in search of his friends and food.

A Truly Antarctic Experience

After a moment to soak in the unique history of Base W, it was time for our own evacuation. We readjusted our gear, summoned our courage, and stepped back into the raging storm. At no time is the warmth and comfort of an old hut more apparent than when stepping from its walls into an Antarctic blizzard.

We managed a few photos, slid down the icy trail, and jumped off the boulders into our bobbing Zodiac. With our mouths full of seawater and drenched clothing encrusted in a thick layer of salt, we moored alongside our mothership, timed the alignment of the gunwale just right, and literally jumped into warmth and safety. The Zodiac that hid behind the iceberg came just a few minutes behind us.

I craved a truly Antarctic experience, and Detaille Island ensured that I got one. Like Steve, maybe I'll find my way back here one day.

Antarctica is an inherently dangerous place. Thanks to the expedition team and crew of the Seabourn Pursuit for calculating every risk and making solid decisions to keep us safe every step of the way.