Somewhere between Argentina and Antarctica, I awoke to chaos.

The cabin lurched violently. Drawers slammed open and closed, bottles rolled across the floor, and the heavy metal door of a safe crashed against the bulkhead like a drum. Every few seconds the ship pitched and rolled to what felt like her extreme limits.

We'd entered the Drake Passage.

Heather stirred beside me, still hoping to sleep through the worst of it. In the dim glow of the night-light, our cabin breathed with the motion of the waves — the walls seemed to flex, and our belongings, which we'd carefully secured before falling asleep, crashed into the sink or rolled across the deck. The ship groaned all night.

A friend once told me: "You'll know you're in the Drake Passage when you wake up on the floor."

He wasn't far from wrong.

The Drake Passage

The Drake Passage stretches six hundred miles between South America and Antarctica, and is where the Atlantic, Pacific, and Southern Oceans collide. At this latitude, no landmass on the planet slows the force (the fetch) of the waves. It's the only place on Earth where water circles the globe uninterrupted— an expressway of wind and waves that has fueled the nightmares of sailors for centuries.

Named for Sir Francis Drake — who never crossed the Drake Passage — these seas became infamous during the age of sail. Before the Panama Canal, all Pacific-bound ships rounding Cape Horn had to face it. More than 20,000 sailors are believed to have died here — crushed by rogue waves, or capsized and frozen in the dark waters.

Despite the stronger hulls and smarter ships of today, the Drake Passage is still not to be taken lightly. In 2022, a rogue wave struck the cruise ship, Viking Polaris. One passenger died and several were injured. Another ship, the Plancius, lost power mid-crossing, which reduced her speed to five knots. She was pummeled for hours before she finally reached safety.

In 2017, a disabled engine on the Silver Cloud left her adrift in the Drake, and in 2010, a wave smashed a window on the bridge of the Clelia II during extremely rough sea conditions.

Intrepid travelers crossing these waters get one of two outcomes: the Drake Lake, or the Drake Shake.

We got the latter.

Unto the Breach

We left Ushuaia, Argentina — the world's southernmost city — aboard the Seabourn Pursuit, an expedition ship designed for polar extremes. Our destination was Antarctica — but those wishing to visit the White Continent have to pay the "Drake Tax."

The Beagle Channel was calm, and the mountains of Tierra del Fuego soon faded into the pale horizon. But after turning south during the night, the sea rose to meet us.

Ours was the forward-most cabin on the ship, which guaranteed that we felt the full range of the ship's vertical movement.

Sleeping on my stomach, I awoke to the bizarre sensation of the bed dropping out from under me. Gravity compensated as my body crashed down onto the bed, and my face landed on the pillow. The bow of the ship mounted the next wave, and the bed dropped again. This process repeated all night.

By morning, the public areas of the ship were mostly empty. Coffee cups skidded off tables. The few passengers who ventured from their cabins staggered from wall to wall, gripped handrails, and laughed nervously. We were tossed around by more than four-meter swells and forty-knot winds, and each impact resonated throughout the ship like a heartbeat.

Stumbling through the passageways, the effects of the Drake were written on everyone's faces. I relied on a cocktail of remedies — a steady supply of Dramamine, patches behind my ear, an electronic pulse bracelet, and firmly-clenched teeth. I've never been prone to seasickness, but queasiness was barely kept at bay.

Another couple we'd met lost their entire breakfast to the Drake— coffee, bacon, and eggs — shattered across their cabin floor and victim of the sea's invisible hand. Mugs and plates could be heard smashing all over the ship, so much so that I wondered if Antarctic cruise operators wrote off a certain percentage of dishware to the Drake Passage.

At a reception that night, the captain of the ship smiled calmly even as the room tilted around him. He addressed the rough seas and mentioned that the worst was nearly behind us.

Nearly, I thought.

Outside, spray whipped across the decks and the horizon disappeared. Under the ship's running lights, the waves weren't just tall — they were living things; assaulting our hull like demons shielded by a flurry of white foam.

My journal from that night (in shaky penmanship) reads:

The Drake Passage has more personality than some people I have met. It is spoken of in hushed tones as if it is a person — a living, breathing soul with moods and temperament. I've now seen firsthand that it lives up to its reputation, and it somehow seems proud of the toll it takes on ships traveling these frigid waters.

Sea Legs

By the end of our second day in the passage, something changed — perhaps not the sea conditions as much as the passengers.

The movement of the ship took on something of a soothing rhythm. I started anticipating each roll, leaning into it rather than resisting. Unease eventually became focus. Even the noise — the constant groaning from the bowels of the ship and the thud of waves against the hull became strangely reassuring.

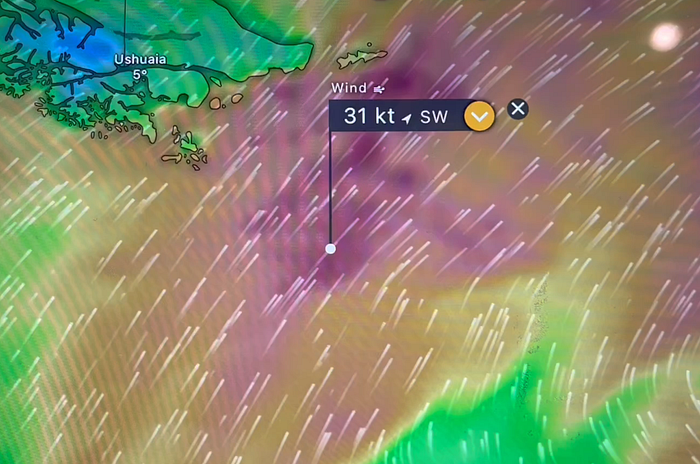

I traced our route on a screen. The course from Argentina wasn't the straight line toward Antarctica that I'd expected, but a looping, zigzag course that looked more like the path of a drunken sailor. The crew later explained that we were weaving between systems, riding the edges of storms rather than their centers.

The seas were getting rougher, and the Pursuit would be the last ship to cross the Drake Passage for the next three days.

The weather window closed behind us.

The Convergence

Later that night, the violence subsided. The waves softened and the ship leveled. We had reached the Antarctic Convergence — the invisible boundary where cold southern waters flow beneath the warmer seas of the north.

At dawn, light-mantled albatross glided off our stern, motionless in the wind. Black and white cape petrels surrounded us. The deck, once deserted, began to fill with curious passengers in brightly-colored parkas, smiling in relief. An eagle-eyed crewmember soon spotted the first iceberg, and not long after — land.

Forty-eight hours after leaving Argentina, we had finally reached the calm waters of Antarctica.

That evening, the Pursuit sailed into the volcanic caldera of Deception Island, and the world transformed. Volcanic cliffs loomed overhead as thick flakes of snow began to fall. We reached the relative safety of the crater — as safe as anyone can be inside an active volcano.

Antarctica greeted us with an incredible sunset. The skies filled with pinks and oranges, and a snowstorm moved in as Pursuit moved deeper into the caldera. The scene was right out of a Jules Verne novel. But like many experiences in Antarctica, the moment was fleeting. The snowstorm enveloped our ship and the colorful skies disappeared as if it had all been some incredible hallucination.

Resolution

Standing on deck in the falling snow, I understood that the Drake Passage is not simply a barrier between continents. It's a threshold. A rite of passage, certainly, and a gateway to one of the least explored frontiers on the planet. It's also a test — of patience, humility, and of faith in seamanship and modern engineering.

It strips you down to the essentials — what you need, what you fear, what you trust — and when it's done with you, it spits you out at the edge of the world.

I looked across the caldera of Deception Island and thought of the sailors and explorers who had crossed these same waters before: Shackleton, Gerlache and Amundsen, yes, but also the nameless deckhands who froze to the railings of their ships. Across time, visitors here were bound by the same thing — a desire to see what's on the other side.

The Drake Passage doesn't just separate the Atlantic from the Pacific. It separates people from who they were before.

Safely anchored within the calm waters of Deception Island, I got the best night's sleep I'd had in days. We spent the next week exploring Antarctica — by all means, the trip of a lifetime. But through it all, a persistent thought festered in the back of my mind.

The return trip would take two days, and the Drake Passage was waiting.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, watch the journey at the link below!

And for more adventures from Antarctica, check out my other stories: