I've always been curious. How many words do you actually need to know to watch a movie without subtitles? To read a novel? To have a meaningful conversation? To claim that you really know the language?

The internet is full of conflicting answers.

Some claimed 500 words were enough to "talk to anyone." Some say 3,000 words is enough. Others insist you need 10,000. Or 20,000.

Or a small miracle.

I got tired of guessing, so I dove into scientific research to see what the studies actually say.

And I hope you've had some coffee, because I'm about to show you more numbers than any language article reasonably should.

But they matter.

My goal here is to put everything in one place so you can see the landscape in black and white: how vocabulary size links to comprehension, which ranges unlock which skills, how your numbers compare to native speakers, and where you can check your own vocabulary size for free.

The Stages of Vocabulary Mastery: From 0 to 12,000 Words

Let me break down exactly how many words you need for each proficiency level and communication goal, based on research.

A small note first.

Throughout this article, I'll be talking about word families, not individual words. A word family counts the base word and its common forms as one unit:

run → runs, ran, running, runner, rerun

All of these together are one word family.

This dramatically reduces the total count.

0–1,000 Words: The Survival Core

The first 1,000 word families are the skeleton, the most common words that appear everywhere. These are the structural bones of speech: pronouns, basic verbs, simple adjectives, and the little glue words that hold sentences together (in, on, at, from).

At this stage, you won't understand much detail yet, but you can understand a simple message. Imagine hearing:

"I want to go to the… [unknown word] … tomorrow. Can you help me?

You still grasp the essential meaning because the core structure (I / want / go / tomorrow / help) is made of these first 1,000 words.

What the 0–1,000 range allows you to do

- introduce yourself and share basic personal details

- ask simple questions ("Where is…?" "How much…?")

- follow predictable, routine phrases

- manage essential travel situations

- understand slow, high-context speech

- start hearing the boundaries between words rather than one continuous stream.

Young children absorbing their first language hear thousands of these words daily, while adult L2 learners often need to acquire this foundation deliberately (Nation, 2013). But once these 1,000 words are in place, you have something solid to stand on. They give you entry.

1,000–2,000 Words: The High-Frequency Foundation

Every language has a small set of frequent words that do most of the heavy lifting.

In English, the first 2,000 word families (a word plus its most common forms) cover 89 % of everyday spoken language (Nation, 2006).

Coverage is not the same as understanding.

Coverage simply means: "Out of every 100 words spoken, you recognize about 89 of them."

Comprehension, on the other hand, means you can actually follow the message in real time.

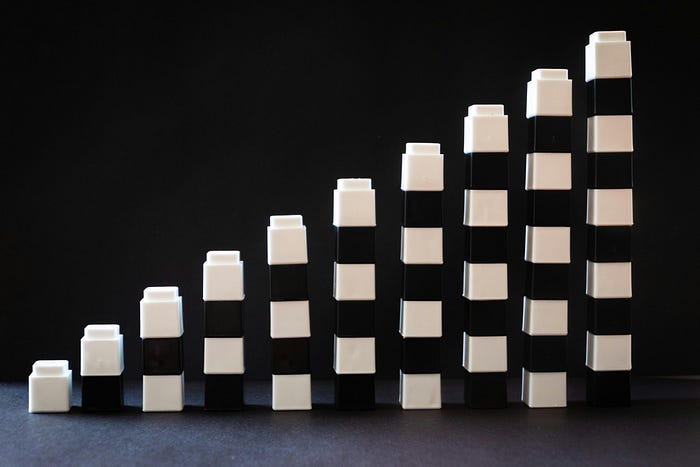

It means that a relatively small vocabulary gives you massive comprehension power. These are your foundation stones — huge, heavy, doing most of the work.

Everything else? Smaller bricks that fill in the gaps.

What 1,000–2,000 range allows you to do

- follow predictable conversations about familiar topics

- understand the general meaning of everyday speech

- begin using subtitles effectively when watching videos

- read short, simple texts without constant dictionary checks

You're not fluent yet, but the language stops feeling slippery. You can finally "hear" what's happening, even if you can't follow everything. This is the stage where you might begin to feel genuine momentum.

3,000–5,000 Words: From Following the Story to Following the Conversation

You've probably seen articles claiming 3,000 words is enough for fluency.

It isn't.

With around 3,000 words, you can follow the storyline of movies, TV shows, and YouTube videos. Research on more than 300 films shows learners at this level can track what's happening with the help of subtitles (Rodgers, 2009a, 2009b).

But when it comes to written texts, things look very different.

With 3,000 word families, you understand about 95% of the words in many general texts (Hazenberg & Hulstijn, 1996). That sounds impressive until you realize what it actually means:

You're missing one word in every twenty.

On a typical page, that's 10–15 unknown words. You can't relax into the reading — you're guessing, patching, and constantly pulled out of the flow.

This is why researchers consistently argue that true contextual learning — the ability to infer the meaning of new words from context — generally begins closer to 5,000–6,000 word families, the point at which learners approach 98% coverage (Nation, 1990; Laufer, 1997). At that level, the gaps are small enough for the brain to fill in naturally.

What this stage allows you to do

- follow the plot of movies and TV without pausing constantly

- enjoy YouTube videos with subtitles and recognize more recurring expressions

- stay oriented in familiar podcasts

- read lighter articles or graded texts with growing confidence

- keep up with everyday conversations unless the topic becomes very specific or technical.

This is the period when real input starts to work for you.

It's not yet comfortable comprehension (that comes at 6,000–7,000 words), but it's the stage where many learners feel, "I finally understand most of what's going on."

6,000–7,000 Words: When Conversation Finally Feels Comfortable

Something shifts when you reach 6,000–7,000 word families.

Suddenly, spoken language stops feeling like a race you're always half a step behind. You can follow conversations as they unfold — not perfectly, but comfortably. This is the range where everyday speech finally has enough familiar vocabulary for most learners to keep up without strain (Nation, 2006).

Interestingly, listening doesn't demand the same level of coverage as reading. Research shows that you can follow spoken language fairly well even with around 95% coverage, because tone, pauses, gestures, and context help you fill in the missing pieces (Van Zeeland & Schmitt, 2012). This is why many learners at this stage look up from their podcasts one day and think, "Wait…I'm actually understanding this."

By now, you've picked up enough mid-frequency vocabulary to catch the things that make conversations feel human — small jokes, little side comments, a shift in tone, the way someone softens or sharpens their meaning with a single adjective.

What this stage allows you to do

- understand most everyday conversations in real time

- follow group discussions without panic when speakers overlap

- enjoy familiar TV shows without subtitles

- read news articles and blogs with reasonable ease

- express yourself with more precision and nuance

It's not fluency in its deepest sense, and it's not full reading mastery, but it's the point where the gap between what you want to say and what you can say finally begins to shrink.

8,000–9,000 Words: When Reading Finally Opens Up

Once you reach 8,000–9,000 word families, the written world of the language becomes available to you.

Webb and Nation (2020) note that this is the level typically required for comfortable comprehension of novels, newspapers, general nonfiction, and most everyday reading materials.

Written language uses far broader vocabulary than speech, and this range finally gives you enough lexical density to follow ideas without constantly stopping to decode individual words.

You still encounter unfamiliar terms (everyone does), but they no longer break the flow. You can stay with the argument of an article, follow a narrative in a novel, and read for pleasure rather than survival.

What this stage allows you to do

- read newspapers, blogs, and general nonfiction with confidence

- follow novels and stories without heavy dictionary use

- understand opinion pieces, essays, and longer texts on everyday topics

- learn new words naturally through context

- engage with the language the way native readers do: for curiosity, interest, and depth

For many learners, this stage marks the beginning of true independence. You no longer need curated materials; the language itself becomes your teacher.

10,000–12,000+ Words: When You Enter the Near-Native Zone

If 8,000–9,000 words let you read comfortably, the 10,000–12,000+ range is where the language starts to feel almost limitless.

This is the territory associated with C2-level comprehension — the ability to understand nearly anything a well-educated native speaker can read or listen to (Milton, 2013; Schmitt, 2014).

At this stage, vocabulary isn't just broader. It's deeper.

You recognize shades of meaning, metaphorical uses, academic language, literary phrasing, and the kinds of abstract or domain-specific terms that appear in essays, research papers, complex documentaries, and high-level debates.

What this stage allows you to do

- read widely across genres — fiction, essays, academic texts, opinion pieces

- follow fast, unscripted conversations on almost any topic

- understand nuance, irony, implication, and subtle shifts in tone

- learn new words directly from exposure, the way native speakers do

- feel "at home" in the language, not just competent in it

There's no fixed ceiling here — native speakers keep learning new words throughout their lives. But reaching this range means you have the vocabulary breadth and depth to participate fully in the intellectual and cultural life.

Academic and Technical Reading: When General Vocabulary Isn't Enough

If your goal is to study or work in a specialized field, the vocabulary story changes. Once you've built a strong base of general words, you'll need an extra layer — the language of academia or the language of your discipline.

For university-level reading, that usually means aiming for around 8,000 word families plus the 570 families from Coxhead's Academic Word List, which covers roughly 8.5–10% of academic writing across disciplines (Coxhead, 2000).

And the bar is rising: research on MOOC lectures shows that many learners need closer to 9,000 words to follow university-style content comfortably (Dang & Webb, 2014).

Technical fields demand even more specialization. One study found that in an anatomy textbook, a full 30% of the vocabulary consisted of technical terms (Chung & Nation, 2003) — words you simply won't meet in everyday English. This means that even if you're strong in general vocabulary, a medical student, an engineer, or a computer scientist still needs to learn the coded language of their field.

In short, the broader your goals, the wider your vocabulary needs to be.

General English gets you far, but academic and technical worlds carry their own "dialects".

A Note on CEFR Levels: Useful Guidelines, Not Guarantees

Learners often want to know how these vocabulary ranges compare to CEFR levels.

The truth is more nuanced than most charts suggest. Research shows clear correlations between vocabulary size and CEFR proficiency, but the relationship is not exact — two learners with the same number of known words may perform very differently depending on their listening skills, grammar knowledge, exposure, and background familiarity with topics (Milton, 2013; Douglas, 2020).

Still, we can sketch a reasonable, evidence-informed map:

- 1,000–2,000 words: A1–A2 range (basic communication)

- Around 3,000 words: approaching B1 for comprehension of spoken content

- 3,000–5,000 words: B1–B2 range for many learners, depending on other skills

- 6,000–7,000 words: strong B2, sometimes lower C1, especially for listening

- 8,000–9,000 words: solid C1 for reading and general comprehension

- 10,000–12,000+ words: C2-level comprehension, depending on depth of knowledge, reading experience, and command of abstract and domain-specific vocabulary.

These are guidelines, not rules.

Vocabulary size strongly supports CEFR performance, but true proficiency also depends on grammar, discourse skills, processing speed, familiarity with topics, and real-world exposure.

But Wait, How Many Words Do Native Speakers Know?

Before you feel overwhelmed by these numbers, let's put them in perspective. How does your target vocabulary compare to that of native speakers?

Studies that measure vocabulary give us a valuable snapshot of what this looks like across different groups:

- Most adults (20–35): roughly 20,000–35,000 word families (Nation & Waring, 1997)

- University entrants: around 10,000 word families

- University graduates: about 17,000 word families (Milton & Treffers-Daller, 2013)

- Highly educated professionals: often 20,000–30,000+ word families — especially academics, journalists, editors, lawyers, and people who read extensively in their field.

Shakespeare, for comparison, used about 31,500 distinct words across all his plays and sonnets combined. Scholars estimate he knew up to 65,000 words total. So yes, Shakespeare probably knew more words than you. But I think you're winning in other departments.

Plus, don't forget that native speakers accumulate vocabulary gradually, over decades of daily exposure. These numbers grow not through deliberate study but through a lifetime of reading, conversation, media, writing, and everyday immersion.

And this perspective matters.

You're not trying to "catch up" to a native speaker's lifetime of input. You're learning the most useful words first, in a focused, intentional way, and progress as you go.

Where to Test Your Vocabulary Size?

If you want a reliable estimate of how many words you actually know, the best place to go is Paul Nation's official vocabulary test collection. His tests are widely used in research, designed for English learners, and free to access.

You can access all of these here.

Here are the three tools worth using:

1. Updated Vocabulary Levels Test (UVLT)

This test measures your knowledge of the first 5,000 word families — the core vocabulary needed for everyday communication, basic reading, and early listening fluency.

It's ideal for beginners through upper-intermediate learners.

2. Vocabulary Size Test

This test estimates your total vocabulary size, up to very advanced levels. If you're aiming for reading fluency (8,000–9,000+ words) or academic English, this is the one to take.

3. Picture Vocabulary Size Test

A visual version designed for children, preliterate learners, or anyone who benefits from image-based prompts. It tests knowledge of the most frequent 6,000 word families.

Why Take a Vocabulary Test at All?

Because guessing doesn't help you plan.

Knowing your number does.

"I think I know a lot of words" is vague.

"I know 4,000 word families, and I need around 6,000 for comfortable conversation" is actionable.

A test gives you:

- a starting point

- a clear target

- a way to measure real progress

Retest every 3–6 months.

Not to chase validation, but because watching that number rise — 4,000 → 4,800 → 5,600 — is incredibly motivating. It turns vocabulary learning from a foggy hope into a concrete, measurable journey.

What Do All These Numbers Actually Mean for You?

We've talked a lot about vocabulary ranges, percentages, coverage, and word families. But numbers only matter if they help you make better decisions as a learner.

So what does all of this actually mean for your daily study life?

1. These ranges give you realistic milestones

Instead of vague goals like "improve my English," you can set targets that match the skill you want to develop. Clear goals remove the guesswork. You know what you're aiming for, and roughly how far you are from it.

2. These numbers help you prioritize

Not everyone needs the same vocabulary size. A software developer spending most of their time in meetings might aim for 6,000–7,000 words. A university student will need academic vocabulary far more than informal slang. A future novelist reading in English will eventually need 9,000–10,000+ words. The point isn't to learn everything. Learn what matters for your life.

3. How you learn matters just as much as what you learn

Research shows explicit learning with flashcards, word lists, and focused drills is fast and efficient.

For example, research on learning word pairs has shown that learners can acquire from 9 to 58 vocabulary items per hour, with an average of 34 (Thorndike, 1908), to as many as 166 L2 words per hour (Webb, 1962). More recently, Cobb and Horst (2001) found that deliberate learning with concordances for an hour a week for two months resulted in 140 to 180 words learned (around 16 to 20 words per hour).

In comparison, incidental learning gains are relatively small and are dependent on the amount of input; words are learned gradually through repeated encounters in context.

4. Be patient with yourself, especially between 4,000 and 9,000 words

This is where vocabulary growth naturally slows down. Mid-frequency words appear less often, which means you encounter them fewer times and learn them more slowly. This doesn't mean you're doing anything wrong. It simply means you're entering the part of the journey that takes time and steady exposure.

When you understand the path ahead, you stop judging yourself for not being "fluent yet."

If you want a concrete set of strategies for learning vocabulary, you can check my article How to Learn 5,000 Words Without Flashcards.

Final Thoughts

Vocabulary isn't just a number. It's the shape of what you can understand, say, read, and feel in a new language. These ranges give you a map, but the real progress comes from the small, steady steps you take.

Native speakers spend their entire lives absorbing vocabulary without thinking about it. You're doing something far more intentional and far more impressive. You're choosing to learn, grow, and expand the borders of your world on purpose.

That takes discipline. And it deserves recognition.

Wherever you are on this journey — 1,000 words, 3,000, 7,000, or more — you're already reshaping your mind in extraordinary ways.

And remember: words are power.

With every new word you learn, you're gathering tools that will stay with you forever.

Thanks for reading!

- If you find my work helpful, follow and subscribe.

- Buy me a coffee if you'd like to support my work ☕

- My Substack newsletter How We Learn Languages

You may also like:

References

Anthony, L., & Nation, I. S. P. (2017). Picture Vocabulary Size Test. Waseda University.

Chung, T. M., & Nation, I. S. P. (2003). Technical vocabulary in specialised texts. Reading in a Foreign Language, 15(2), 103–116.

Coady, J., Magoto, J., Hubbard, P., Graney, J., & Mokhtari, K. (1993). High frequency vocabulary and reading proficiency in ESL readers. In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary learning (pp. 217–228). Ablex.

Cobb, T. (2016). The limits of liberalism in L2 vocabulary learning: Empirical support for explicit instruction. Language Teaching, 49(4), 1–16.

Cobb, T., & Horst, M. (2001). Reading and vocabulary learning: The effect of students' written output. Language Learning Research Club, University of Michigan.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213–238.

Dang, T. N. Y., & Webb, S. (2014). The lexical profile of academic spoken English. English for Specific Purposes, 33, 66–76.

Douglas, S. R. (2020). Vocabulary knowledge and its role in L2 reading. The Language Scholar, 6, 1–19.

Hazenberg, S., & Hulstijn, J. H. (1996). Defining a minimal receptive second-language vocabulary for non-native university students: An empirical investigation. Applied Linguistics, 17(2), 145–163.

Hirsh, D., & Nation, I. S. P. (1992). What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimplified texts for pleasure? Reading in a Foreign Language, 8(2), 689–696.

Hunt, A., & Beglar, D. (2005). A framework for developing EFL reading vocabulary. Reading in a Foreign Language, 17(1), 23–59.

Laufer, B. (1997). The lexical plight in second language reading. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition (pp. 20–34). Cambridge University Press.

Laufer, B. (2003). Vocabulary acquisition in a second language: Do learners really acquire most vocabulary by reading? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 59(4), 567–587.

Laufer, B., & Ravenhorst-Kalovski, G. C. (2010). Lexical threshold revisited: Lexical text coverage, learners' vocabulary size and reading comprehension. Reading in a Foreign Language, 22(1), 15–30.

Milton, J. (2013). Measuring the contribution of vocabulary knowledge to proficiency in the four skills. In C. Bardel, C. Lindqvist, & B. Laufer (Eds.), Linguistic perspectives on the vocabulary of second language learners (pp. 57–78). Eurosla.

Milton, J., & Treffers-Daller, J. (2013). Vocabulary size revisited: The link between vocabulary size and proficiency. Multilingual Matters.

Nation, I. S. P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. Heinle & Heinle.

Nation, I. S. P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(1), 59–82.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning vocabulary in another language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I. S. P., & Beglar, D. (2007). A vocabulary size test. The Language Teacher, 31(7), 9–13.

Nation, I. S. P., & Crabbe, D. (1991). A survival language learning syllabus for foreign travel. System, 19(3), 191–201.

Nation, I. S. P., & Waring, R. (1997). Vocabulary size, text coverage and word lists. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 6–19). Cambridge University Press.

Rodgers, M. P. H. (2009a). Vocabulary demands of television programs. Language Learning, 59(2), 335–366.

Rodgers, M. P. H. (2009b). The lexical coverage of television programs. Applied Linguistics, 30(3), 689–710.

Schmitt, N. (2014). Size and depth of vocabulary knowledge: What the research shows. Language Learning, 64(4), 913–951.

Thorndike, E. L. (1908). Memory for paired associates. Psychological Review, 15, 122–138.

Van Zeeland, H., & Schmitt, N. (2012). Lexical coverage in L1 and L2 listening comprehension: The same or different from reading comprehension? Applied Linguistics, 34(4), 457–479.

Webb, S. (1962). The effects of memory training on paired-associate learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 1(3), 173–181.

Webb, S. (2007a). The effects of repetition on vocabulary knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 28(1), 46–65.

Webb, S., & Nation, P. (2020). Teaching vocabulary. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (pp. 1078–1085). Wiley-Blackwell.