Where all your languages live, why they mix, and 10 expert ways to keep them apart

A reader recently left a comment on my article How to Learn a Language that perfectly captured a question many multilinguals wonder about:

"When I try to speak Spanish, my brain hands me a word in Hungarian. Or French. It's as if I have two boxes in my brain: one marked English and one marked Foreign. But I want four: English, French, Spanish, and Hungarian. Any suggestions?" — Patricia Finney, Medium reader (shared with permission)

If you've ever learned more than one language, you've probably experienced this, too.

You're mid-sentence in French when your brain serves you an Italian word. Or you try to say okno ("window") in Polish, but the Swedish word fönster sneaks in instead. Or maybe the word vanishes altogether right when you need it most.

As a language teacher, there's nothing more frustrating, and frankly, embarrassing, than blanking on a word in front of my students. I've used it multiple times, I know it, and yet my brain gives me silence.

It feels like your brain is overloaded, disorganized, or betraying you. But in reality, it's doing something remarkable.

What feels like a glitch is actually the sign of a complex, high-powered system juggling multiple languages in real time. The problem is that we rarely understand how our brain works, let alone how to train it.

We often picture language learning like organizing files into folders. One for French. One for Spanish. One for Hungarian. Pull open the right one, grab the word you need, and go.

But that's not how your brain works. Not even close.

Before I formally studied the science of second language acquisition, I had the same questions you probably do:

- Where do all my languages live in the brain?

- Why do some words come instantly while others get stuck?

- Why do languages blend, mix, or disappear, only to return later?

- And how can I manage them better?

I'm a multilingual speaker of eight languages, a language teacher, and a researcher with a Phd in Applied Linguistics. My work focuses on multilingualism and the individual factors that influence how we learn, store, and manage languages.

This guide will take you deep into the multilingual mind and give you practical tools to train it.

You will discover:

- Where languages are stored in your brain, and why there's no such thing as language "boxes"

- How your mind processes and switches between languages and why it sometimes fails

- Why code-switching and interference are normal (and even useful)

- How dormant languages come back to life

- And 10 powerful, research-based strategies to strengthen your multilingual brain

Whether you speak two languages or seven, this article will help you understand and trust your brain a little more.

How Does the Brain Store Multiple Languages?

Your Mental Lexicon as a Living System

Are your languages stored in separate "boxes"?

Not quite.

Your brain doesn't file words away like folders in a cabinet. Instead, it builds a single, dynamic network of meanings and associations.

This is your mental lexicon — an internal dictionary that links all the words you know across languages, not by alphabet or language, but by concept.

The brain doesn't divide languages into separate compartments like drawers in a filing cabinet.

Instead, it builds a multilevel concept map — an interconnected web of meanings and forms, with core meanings at the center and language-specific words branching out in different directions, like spokes on a wheel.

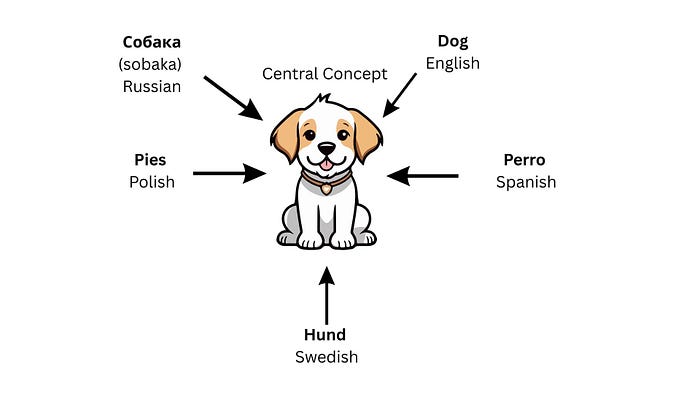

Take the word dog.

You don't store it five times in five different places. You store the idea of a barking, furry animal and tie it to words like a dog (English), el perro (Spanish), pies (Polish), en hund (Swedish), and sobaka (Russian).

These are cross-linguistic links — multiple labels pointing to one shared concept.

But it goes deeper.

Each word carries personal memories and emotions.

A dog might remind you of a childhood pet, el perro of your Spanish class, and pies of your grandparents' house. These emotional associations affect how fast a word comes to mind, depending on what feels most familiar in the moment. These are word-to-concept associations — personal links between the form of a word and the concept it expresses.

As you learn, the way your brain connects words changes:

- At first, you access new words through your native language — you think in your first language (L1) and translate into a second language (L2).

- As proficiency increases, the brain builds direct links between the L2 word and its meaning. Translation is no longer needed. This is why experienced multilinguals can "think" directly in their target language.

- Eventually, all your languages plug into one shared concept system, just with different access speeds.

This is the Revised Hierarchical Model (Kroll & Stewart, 1994), and it helps explain how multilinguals move from translating to truly thinking in a language.

So no, your brain doesn't separate your languages into neat boxes. It builds an evolving, interconnected web — one that adapts to your use, context, and emotional experience every day.

Where in the Brain Are Languages Stored?

Your brain doesn't assign each language its own space.

Whether it's your first or fifth, all your languages share the same core brain regions, mostly in the left hemisphere:

- Broca's area: language production

- Wernicke's area: language comprehension and meaning

- Temporal lobes: store word meanings (semantic memory)

- Hippocampus: links new words to memory and experience

- Auditory cortex: processes sounds, pronunciation, and rhythm

So when you speak Spanish or German or Japanese, the same areas are activated, but the pattern and intensity depend on things like how well you know the language (proficiency), how old you were when you learned it, and what kind of task you're performing (Perani et al., 2003; Abutalebi, 2008).

In short:

- Early-acquired languages run smoother, like muscle memory

- Later-acquired ones may need more cognitive effort and support

But all languages tap into the same neural architecture.

They don't live in isolated "drawers."

Instead, they function more like apps running in parallel, constantly updated based on context, attention, emotion, and your intent. And in multilinguals, those apps compete, collaborate, and influence one another in real time.

Your brain doesn't go:

"Let me open the French drawer."

It says:

"Here's the idea. Which language gets me there fastest?"

Multilingual brains don't store more. They adapt more. And they're incredibly good at doing it on the fly.

How the Brain Processes and Switches Between Languages

How does your brain decide what to say, in which language, and when?

The Multilingual Brain Is Always in Motion

In real life, you don't use languages one at a time. You move between them. Sometimes slowly. Sometimes without noticing.

But your brain doesn't "switch off" unused languages. It activates multiple languages at once, keeping them in the background. Then, in real time, it decides:

- Which one to use

- Which ones to suppress

- Which rules and sounds belong to which system

This balancing act is managed by your executive functions — the high-level mental skills that live in the prefrontal cortex (your brain's "control tower"). They handle attention, working memory, inhibition, and task-switching — all crucial for multilinguals (Green, 1998).

Imagine your brain as a massive traffic control center.

Words, rules, and meanings from all your languages are all racing down different lanes. When everything's flowing (you find the right word, build a sentence, speak smoothly), the traffic is perfectly timed.

But when something clogs the system, like forgetting a word, code-switching, or mixing up grammar, the lanes get jammed. Your brain has to quickly reroute.

Maybe the road to the Polish word okno is temporarily blocked, so your brain reroutes and grabs the Swedish fönster instead.

Maybe two "vehicles" (perro and pies) reach the intersection at the same time, and your brain has to decide who gets the green light.

Your brain is continuously adjusting routes, redirecting traffic, and smoothing over potential collisions in real time.

It's a sign of a fast-moving, adaptive brain constantly negotiating priorities and choices on the go.

Jessner's Dynamic Model: The Brain Doesn't Just Store — It Adapts

Early theories imagined language systems as neatly stacked folders. One language here, another there.

But modern research confirms that languages interact. Constantly.

According to Jessner's Dynamic Model of Multilingualism (2003, 2008), all your languages influence one another, reshape each other, and shift depending on:

- Context (Who are you speaking with? Where are you?)

- Dominance (Which language do you use most often?)

- Recency (Which language did you use five minutes ago?)

- Cognitive load (Are you tired? Distracted? Under pressure?)

This interaction means your Spanish can help you understand French grammar. Your German might influence your English rhythm. Your Italian accent might sneak into your Spanish words.

It's all part of a living system.

This system is non-linear and self-regulating, meaning every language you learn feeds into and modifies the whole.

It's like pouring different colors into one glass. They don't sit still. They blend, ripple, and respond to motion.

From Chaos to Control

To manage this dynamic system, your brain relies on two core abilities:

- Metalinguistic control — the skill of selecting the right language and suppressing the others.

- Metalinguistic awareness — your growing understanding of how language systems work: word order, grammar, structure, tone.

These skills explain why multilinguals often become better at noticing patterns, identifying errors, and learning new languages faster. The more languages you manage, the sharper your awareness becomes (Jessner, 2008).

And though the system gets stronger over time, it still takes effort. Speaking three or four languages isn't just a linguistic flex but a constant act of cognitive regulation.

The positive thing is that every moment you switch, self-correct, or pause to find the right word, your brain is leveling up and building an elegant, adaptable system that gets better with every challenge.

Code-Switching: When Switching Is the Norm, Not the Error

Multilinguals often mix languages in the same sentence, thought, or conversation — a phenomenon known as code-switching. And while it can feel chaotic, it's often a completely normal, even strategic part of using multiple languages.

There are two types of code-switching:

Intentional Code-Switching

This is when you consciously switch to another language for effect, clarity, or cultural expression. Maybe the word comes faster in that language. Maybe it captures the mood better. Maybe it just feels right.

Inter-sentential: Switching between sentences.

- "I'm going to the store. Luego te llamo."

Intra-sentential: Switching inside a sentence.

- "Can I klappa katten?" (My daughter, mixing English and Swedish.)

Tag-switching: A single word or phrase switches.

- "It was fun, si?"

I do it, too. I'll say: "Jag är så trött today, I need a siesta." Three languages. One sentence.

This mixing isn't random. It often serves a purpose, like:

- Filling in gaps when you can't recall a word

- Expressing emotion more naturally

- Signaling identity or belonging in multilingual settings

In fact, research shows that code-switching is especially common among balanced bilinguals and multilingual families (Poplack, 1980; Grosjean, 2001). It is a shared code, a way to connect.

Unintentional Code-Switching

This happens when you involuntarily switch to a word or phrase from another language, often because that language is more accessible in the moment. It's a lexical selection issue: the wrong language's word "wins the race" and comes out first.

For example:

- You're speaking Polish and accidentally say fönster instead of okno.

- You're trying to use Spanish, but an Italian word slips out.

- You insert an English word mid-sentence because it comes faster.

This is especially common when:

- You've recently used the "wrong" language

- Your languages are structurally similar

- You're tired or distracted

- One language is much stronger than the others

So, unintentional code-switching = saying the wrong word from the wrong language (form-level intrusion).

It's about which language's word is selected during speech planning, usually by mistake.

Language Interference: When Languages Help or Hurt Each Other

Interference is more structural than simple mixing. It refers to the influence of the rules of one language (grammar, syntax, or pronunciation) on how you use another (Odlin, 1989).

In short:

Interference = applying the wrong rule from the wrong language (structure-level intrusion)

For example,

- Saying "I very like it" in English because you're transferring word order from Polish.

- Using Slavic word order in English

- Dropping French nasal vowels into your Spanish

But not all interference is harmful.

Positive Transfer (Helpful Interference)

Sometimes your languages support each other. This is called positive transfer, and it occurs when knowledge from one language makes learning or using another easier. For example:

- If you know Spanish, learning Italian vocabulary can feel intuitive

- Grammatical similarities (like adjective placement or verb endings) can speed up comprehension

- Even phonological awareness can transfer, making it easier to hear and pronounce new sounds

This kind of overlap boosts learning and speeds up progress, especially when the languages are structurally similar.

Negative Transfer (Harmful Interference)

But those same similarities can also cause problems. That's negative transfer — when features from one language intrude incorrectly into another, such as:

- Using a false friend: embarazada in Spanish doesn't mean embarrassed

- Applying the wrong grammar rule: using English word order in German

- Pronouncing words with the wrong accent or intonation from another language

Negative transfer often leads to errors, hesitation, and frustration, especially when speaking under pressure or switching frequently.

Like unintentional code-switching, interference results from the co-activation of multiple languages and relies on inhibitory control to suppress the non-target system (Green, 1998). When that control is weakened (by fatigue, stress, or similarity between languages ), interference and switching become more likely.

But with use and awareness, your brain gets better at choosing the right path.

How the Brain Retrieves Words

Why You Forget Words You Know and Find Ones You Didn't Mean to Use

You're mid-conversation. You know the word. You've used it a hundred times. But suddenly… blank. Or your brain serves up the wrong word entirely.

Why?

Because language retrieval is not a neat, one-language-at-a-time process. It's a competition. And your most dominant, well-trodden pathways tend to win the race.

Language Retrieval Is a Competitive Race

Like I said, when you try to speak, your brain doesn't just open a single "language file." It activates all your known languages in parallel due to a process known as non-selective lexical access (Kroll & Tokowicz, 2005).

Imagine standing in a room full of people, all offering suggestions at once. You only want one word, but every language you know is whispering in your ear.

Say you're trying to say "window." Your brain activates:

- window in English

- fenêtre in French

- okno in Polish

- fönster in Swedish

Each one is like a racer at the starting line, competing to reach your tongue first.

Which Word "Wins"? It's Not Random

The one with the strongest, fastest access. And that depends on:

- Frequency of use — the more often you say it, the faster it comes

- Age of acquisition — words learned early are better wired

- Emotional salience — meaningful or emotionally charged words come quicker

- Contextual richness — words used in varied, vivid contexts are easier to retrieve

So even if you're trying to speak Polish, your brain might hand you window simply because you use it daily. Or if your last conversation was in Spanish, your brain might be biased toward ventana.

It's not that you don't know the right word. Your brain is simply optimizing for speed and availability.

Why Do Words From the Wrong Language Intrude?

This retrieval competition is why multilinguals often experience "word intrusions." Your brain is doing its best to optimize communication, choosing the route that feels most available and practiced.

Think of each word in your brain as a route to a destination — the idea you want to express.

- Your native language is like a smooth, high-speed freeway — fast, efficient, automatic.

- Your dominant second language is like a major road — familiar but with occasional traffic.

- Your third and fourth languages might be narrower roads — slower, requiring more effort.

- A rarely used language could be a gravel back road, still there, but hard to reach quickly.

And sometimes, two highways, like Spanish and Italian, run so close together that you accidentally take the wrong exit.

According to Green's (1998) Inhibitory Control Model, your brain constantly works to suppress the languages you're not trying to use. It's like a mental traffic cop: letting the right words through, holding the rest at a red light.

But this system takes effort.

When you're tired, stressed, or distracted, that control slips. You say gracias in a Swedish café. Hallo pops up during your English conversation.

And when languages are closely related (sharing words, grammar, or sounds), the brain has to work even harder to keep them apart.

From a processing point of view, this is normal. From an emotional point of view, it can feel like your brain is playing tricks on you. But in fact, it shows that your brain is fast, flexible, and managing a complex multilingual system on the go.

Tip-of-the-Tongue Moments: What's Really Going On?

Ever had that almost-there feeling? You know the word, it's on the tip of your tongue… but it won't come out.

Psycholinguists call this a Tip-of-the-Tongue (TOT) state (Brown & McNeill, 1966). It happens when your brain activates the concept but temporarily loses access to the phonological form (the sound structure of the word).

This usually means:

- A similar word from another language is getting in the way (like silla blocking Stuhl).

- The retrieval pathway is rusty due to a lack of use.

- Or you're under stress, and your brain's control center is overwhelmed.

Dormant Languages Don't Die — They Sleep

Ever thought you forgot a language, only to have it rush back after a trip abroad or a single conversation?

That's not loss. It's dormancy.

When a language goes unused, it fades into the background of your mental map. But it never truly disappears. The neural pathways are still there. They are just quieter and slower to activate.

Gabryś-Barker (2005) found that in multilinguals, words aren't lost, but shift based on context. Your brain stores them in a flexible, responsive way, ready to reawaken with the right trigger.

And those triggers are often emotional or sensory:

- A childhood song in Russian

- The smell of Spanish churros

- The sound of Italian espresso cups clinking in Florence

This is called the encoding specificity principle (Tulving & Thomson, 1973). We remember things best when the context at recall matches the context at learning.

That's why learning with music, scents, or settings can make words stick more deeply. The more sensory hooks you create, the easier it is to find the words again, even after years of silence.

10 Brain-Boosting Strategies for Multilingual Minds

1. Build 'Language Islands'

Multilingual brains crave clarity.

One of the simplest ways to reduce confusion is to give each language its own space in your routine — a "language island."

These "language islands" act like mental territories where only one language is allowed to live, breathe, and grow.

A language island can be:

- a time slot (Tuesday mornings = German),

- an activity (Swedish during bedtime reading),

- a place (Spanish on the couch with your tutor),

- or a person (only speaking English with a colleague).

You're more likely to recall words if your current context matches the one in which you learned or practiced them.

So when Spanish always happens at 10 am with coffee, your brain gets the message: Time to think in Spanish.

Some suggestions:

- Assign slots in your calendar:

- Monday & Wednesday = Spanish journaling

- Tuesday & Thursday = German news + vocab apps

- Saturday = Swedish films or audiobooks

2. Stick to one language per setting:

- German during chores, Spanish while cooking, Swedish before bed.

The more consistent your "islands," the clearer your brain's map becomes, and the easier it is to find the right words when you need them.

2. Color-Code and Visually Separate Your Languages

With multiple languages in your head, even your notes can become a source of confusion.

Color-coding is a simple tool to help your brain keep things organized visually and mentally.

Your brain loves cues.

According to dual coding theory (Paivio, 1991), combining visual and verbal information strengthens memory and reduces mental overload. Giving each language a distinct visual identity through color, format, or layout helps your brain instantly know: This is Spanish, not German.

- Assign a color to each language

- Spanish = red

- German = green

- Swedish = yellow

- English = black

2. Apply it across the board

- Use separate notebooks, highlighters, tabs, or app themes. If you journal in multiple languages, divide pages with color-coded sections or borders.

3. Make grammar visual

- In German, you could highlight der nouns in blue, die nouns in red, and das in green. In Spanish, highlight verb endings or irregular forms with colored markers.

4. Label your space

- Add color-coded sticky notes around the house, e.g., a red label for ventana (window) in Spanish, a blue one for fenêtre in French. Your home becomes an immersive visual dictionary.

This can be especially helpful for similar languages. For instance, Spanish and Italian can feel like linguistic twins. But visual cues give your brain a scaffold — a way to tag each word to the right system and avoid those neural "traffic jams."

In time, your brain won't just remember what something means. It'll remember what it looked like, where it was written, and what language it belonged to.

Color becomes part of the memory. A shortcut to fluency.

3. Do Switching Drills

Mixing languages on purpose, like a DJ mixing tracks, might sound like a recipe for confusion, but it's actually one of the best ways to train your multilingual brain.

Most interference happens when your control system gets overwhelmed. But executive control — the brain's ability to switch tasks, inhibit distractions, and stay focused — can be trained, just like a muscle (Prior & Gollan, 2011; Verreyt et al., 2016).

Intentional language switching strengthens your ability to activate one language while suppressing the others. Think of it as mental CrossFit — challenging, but transformative.

- Tell a story, switch languages

Rotate every sentence or paragraph.

Example:"I made some coffee." (English) — "Luego me senté en el sofá." (Spanish) — "Und dann habe ich Nachrichten gelesen." (German)

2. Bilingual character dialogues

Write or record a dialogue where one "character" speaks one language, and the other responds in another.

3. Shuffle language cards

Use index cards with language names. Shuffle a deck where each card tells you which language to speak. Pick one and continue the story in that language until the next card.

4. Translation relays

Take one sentence and translate it through a language chain. Reflect on how it changed.

E.g., English → German → Italian → back to English.

This technique also improves your metalinguistic awareness — noticing grammar, structure, and false friends across languages. You'll start seeing how your languages influence one another and how to keep them apart.

4. Develop Distinct Language Personas

Have you ever felt slightly different when speaking Spanish versus German? Maybe more expressive in one, more reserved in the other?

Multilinguals often shift tone, body language, and even personality across languages. You can use this to your advantage.

Creating "language personas" helps your brain separate and organize your languages.

Instead of one big multilingual tangle, each language gets its own voice, mood, and identity. This activates different neural networks and strengthens your retrieval control (Dewaele & Nakano, 2013).

Think of it like acting.

You're not just speaking another language. You're stepping into a slightly different version of yourself.

- Assign each language a personality or role

- Spanish = passionate storyteller

- German = precise thinker

- French = romantic dreamer

2. Create a short backstory for each persona

Where do they live? What do they do? How do they speak?

3. Act the part

Use different facial expressions, intonation, and posture in each language. You're not just speaking differently, you're becoming someone else.

4. Use shadowing for full-body imitation

Watch native speakers and mimic everything: pronunciation, tone, gestures, and rhythm. This activates the mirror neuron system (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004), helping you embody the language fully.

5. Switch personas when you switch languages

This mental reset boosts recall and fluency. Your brain gets a clear signal: we've entered Swedish mode now.

6. Anchor personas to real-life contexts

Speak French at cafés or with romantic books, English for work and email, Russian with family. The clearer the boundary, the less overlap in your mental system.

These personas create emotional and contextual walls between your languages, making them easier to manage. The more you commit to your personas, the easier it becomes to stay in the right lane, with the right voice, in the right language.

5. Speak to Yourself: Voice Notes and Self-Talk for Fluency and Control

Want to boost fluency, confidence, and control without a teacher, partner, or class?

Talk to yourself out loud. In all your languages.

Self-talk is one of the most effective ways to turn passive knowledge into active. When you speak, you force your brain to retrieve words, organize grammar, and monitor your output in real time.

- Record 1–2 minute voice notes

Describe your day in Spanish. Summarize a news article in Polish. Recall a memory in Italian. React to a quote in Swedish.

2. Listen back and reflect

Notice hesitations, missing words, or grammar slips. Repeat the same message faster, clearer, and smoother.

3. Try transcription tools

Use apps like Otter.ai or Whisper to see what you said. Analyze your sentence structure, tenses, and vocabulary.

4. Vary your goals

One day, focus on speed. Another, on grammar.

Try changing tone — explain like you're teaching a child, or narrate with dramatic flair.

5. Add switching challenges

Mid-story, switch to another language (see Strategy 3). Practice staying in control as your brain shifts gears: "I was walking through the park this morning…" → switch to Spanish → "hacía sol, y escuché los pájaros…" → switch back.

Self-talk activates what Swain (2006) calls productive language control — the ability to plan, produce, and monitor language as you speak. And according to Bassetti (2008), private speech boosts self-regulation and switching skills — two key advantages for multilinguals.

Speaking forces your brain to create, not just consume, language. So next time you're walking or cooking, talk to yourself. In Spanish, then Italian. Or all the languages you know.

6. Play Translation Games to Strengthen Language Boundaries

Translation games are a fun way to improve fluency while reducing interference between your languages.

These exercises train your brain's inhibitory control — the ability to activate the right language and suppress the rest (Green, 1998).

They also boost cross-linguistic awareness, helping you spot tricky overlaps in structure or meaning (Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008).

Back-and-Forth Translation

- Pick 3–5 short sentences in your stronger language.

Example (Spanish):

Fui al mercado. Compré pan. Estaba lloviendo. "I went to the market. I bought bread. It was raining."

- Translate into your weaker target language.

Example (Italian):

Sono andato al mercato. Ho comprato del pane. Pioveva.

- Pause and analyze: Would a native say it this way? Did you carry over Spanish word order or phrases? Are prepositions or verb forms slightly off?

- Stay in the second language (Italian). Instead of translating back, expand the story in that language only. This builds depth without reinforcing cross-transfer errors.

Triple-Hop Challenge

Translate the same idea through multiple languages, e.g.: English → Spanish → Italian

- English: "I'm tired today. I didn't sleep well. I have a lot to do."

- Spanish: Estoy cansado hoy. No dormí bien. Tengo mucho que hacer.

- Italian: Sono stanco oggi. Non ho dormito bene. Ho molto da fare.

Now correct and reflect:

- Did you mix up prepositions or tenses?

- Were there false friends, like actual vs attuale or asistir vs assistere?

- Which parts felt automatic? Where did you hesitate?

Use tools like DeepL, Reverso, or ChatGPT to check or ask a native speaker.

Once you've written it, read all versions aloud. This helps activate your spoken language systems and highlights mismatches between your written and verbal fluency.

Translation games build stronger boundaries between languages by forcing contrast and clarity. You start to see how each system handles meaning, structure, and form, and your brain becomes faster at retrieving the right pattern at the right time.

7. Create Multilingual Mind Maps

Unlike vocabulary lists that isolate words, multilingual mind maps mirror your brain's mental lexicon — a web of meanings.

Semantic network models (Collins & Loftus, 1975) show that activating one word can trigger a chain reaction of related concepts. Mind mapping taps into that same spreading activation.

- Choose one concept or theme per map: Travel

- Use at least three languages per map. Place the word in each language side by side.

Central theme: Travel / Viaje / Viaggio / Reise

Subtopics: Transportation — English: train, Spanish: tren, Italian: treno, German: Zug.

Useful Phrases — Where is the hotel? — Spanish: ¿Dónde está el hotel? Italian: Dov'è l'hotel? German: Wo ist das Hotel?

- Color-code by language (e.g., red for Spanish, green for Italian)

- Add visuals: Draw icons (plane, suitcase, hotel bed) next to words

- Practice: Tell a story about your last trip using all four languages

- Highlight false friends like: actual in Spanish = current, not actual, "libreria" in Italian = bookstore, not library, eventuell in German = maybe, not eventually.

8. Interleave Your Languages to Build Flexible Recall

Interleaving is a smart learning technique where you mix languages, skills, or topics in a single study session instead of studying them in blocks (30 minutes of just French).

Interleaving is like building a stack of pancakes layered with different fruits. Each pancake is a skill or language, and the fruit between adds flavor and contrast — vocabulary in Spanish, grammar in German, listening in Swedish. Mixing them may feel messier than focusing on one at a time, but just like this delicious stack, the variety makes it richer, more memorable, and far more satisfying.

Interleaving challenges your brain to choose the right word, rule, or sound from a set of similar options. This boosts long-term retention and retrieval (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007; Birnbaum et al., 2013), and strengthens task switching and inhibition (Green & Abutalebi, 2013).

In the context of language learning, interleaving might mean:

- Switching between languages (e.g., Spanish, German, Swedish) in one session

- Practicing speaking, writing, listening, and grammar in alternating order

- Mixing vocabulary from different semantic categories or languages

- Switch languages every 10–15 minutes

Study Spanish, then German, then Swedish within the same hour.

2. Rotate between skills

Listen to a podcast in one language, read an article in another, then write or speak in a third.

3. Use mixed flashcard decks

Shuffle vocabulary from all your languages together. Add color tags to help your brain spot the difference.

4. Try themed prompts in different languages

- What did you eat yesterday? → Spanish

- Describe your last vacation → German

- Share a childhood memory → French

5. Flip the context

- Watch a video in Italian, summarize it in English, then discuss it in Spanish.

Interleaving makes your practice more dynamic and builds the mental flexibility you need to switch, stay sharp, and speak all your languages with confidence.

9. Calibrate Proficiency to Reduce Unwanted Code-Switching

When your languages are unbalanced, your strongest one tends to intrude. But by strengthening the weaker ones, you reduce interference and give your brain more reliable routes to follow.

Bilinguals with better expressive vocabulary in a language are less likely to switch unintentionally (Grey & Tokowicz, 2022). So if you want fewer slips and more control, don't just practice randomly. Target what needs strengthening.

- Audit your skills

Rate yourself in speaking, listening, reading, and writing for each language. Where do you struggle? Be specific. Maybe your French reading is strong, but speaking feels clumsy. That's your starting point.

2. Align practice with your goals

Want to stop switching mid-conversation? Prioritize speaking drills. Need to write better formal emails? Focus on writing flow and vocabulary depth.

3. Create micro-sessions

Short, focused practice beats long, vague study.

Try recording a daily voice memo in your weaker language, shadowing short native videos, building semantic field maps (e.g., all words related to travel or food), doing translation drills with tricky grammar points.

4. Track and tweak

Review your output. Notice when and where you still default to another language. Adjust your next practice accordingly.

Over time, those weaker circuits will get stronger. The mental highways will smooth out. And your brain will stop reaching for the easier word, because will have options.

10. Explore the Power of Semantic Field Drills

Ever find yourself knowing the word "run" in Spanish (correr) but blanking on "crawl" or "swim"?

That's because your brain didn't store these words together. It stored one isolated word, not the unifying idea behind it.

So, what's a semantic field?

The word semantic comes from Greek semantikos, meaning "meaning." So semantics is simply the study of meaning in language.

A semantic field is a group of words that belong to the same "family of meaning". For example:

- The field of movement includes run, walk, swim, fly, crawl.

- The field of emotions includes happy, sad, angry, afraid.

- The field of speech includes say, ask, explain, shout, mumble.

Words in the same semantic field often appear in similar contexts. They're neighbors in your mental map, and if you train them together, you build a stronger, faster memory network.

Language isn't stored alphabetically in your head. Instead, it's stored by meaning. One idea triggers another, like a domino effect.

This strategy is grounded in semantic network theory (Collins & Quillian, 1969), which shows that the more related concepts you link, the faster and more accurately you retrieve them.

For multilinguals, building semantic fields in each language and across them prevents confusion, strengthens associations, and reduces code-switching.

- Pick a theme

- Movement: run, walk, swim, fly, crawl

- Emotions: love, anger, fear, joy, envy

- Food: cut, boil, bake, chew, swallow

- Weather: rain, storm, snow, fog, sunshine

2. List the Words in Each Language For movement:

3. Use Them in Context

Write or speak short examples:

- English: The baby crawled under the table.

- Spanish: El bebé gateó debajo de la mesa.

- Italian: Il bambino ha gattonato sotto il tavolo.

- German: Das Baby ist unter den Tisch gekrochen.

4. Tell a Micro-Story

Build a mini-story using as many field words as possible:

"Yesterday, I walked to the park, ran after my kid, and swam in the lake — all before 10 a.m.!"

Say it in each language, and feel how it flows when the words are connected by meaning.

5. Rotate Weekly

- Each week, switch to a new semantic field.

- Create your own maps.

- Write, speak, record, and draw connections.

Final Words

Pause for a moment and acknowledge what you're really doing here. You're not just memorizing words or grammar rules.

You're building one of the most complex and beautiful systems the human brain can manage — a multilingual mind.

Every time you retrieve a word or switch between languages, your brain is doing high-level executive work. It's filtering, prioritizing, inhibiting, adapting.

In this guide, you've seen how your languages live and interact in your brain. You learned that your brain is not a filing cabinet, but a dynamic transportation network, a flexible ecosystem of meaning and memory.

And now, you have practical strategies to guide that system: to strengthen the right circuits, reduce interference, and thrive as a multilingual speaker.

So the next time you hesitate, mix up two words, or pause to remember a phrase, don't doubt yourself. Realize that your brain is doing something extraordinary.

With every new language you attempt to learn, you're becoming not just smarter, but more adaptable, creative, and cognitively flexible than you think. And every time you show up to practice, you're not just learning a language. You're changing the way your brain works for life.

Keep learning.

Thanks for reading!

If you found this helpful, follow and subscribe.

And if you'd like to support my work, you can buy me a coffee ☕️ — a kind gesture that fuels the long hours I spend researching, writing, and simplifying science with love… often with a small baby on my lap 💛

References

- Abutalebi, J., & Green, D. W. (2007). Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language representation and control. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 20(3), 242–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2006.10.003

- Bassetti, B. (2008). Self-repair in L2 and FL oral narratives. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 46(2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1515/IRAL.2008.008

- Birnbaum, M. S., Kornell, N., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2013). Why interleaving enhances inductive learning: The roles of discrimination and retrieval. Memory & Cognition, 41, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0272-7

- Brown, R., & McNeill, D. (1966). The "tip of the tongue" phenomenon. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5(4), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(66)80040-3

- Collins, A. M., & Quillian, M. R. (1969). Retrieval time from semantic memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 8(2), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(69)80069-1

- Collins, A. M., & Loftus, E. F. (1975). A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological Review, 82(6), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.82.6.407

- Dewaele, J. M., & Nakano, S. (2013). Multilinguals' perceptions of feeling different when switching languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2012.712133

- Gabryś-Barker, D. (2005). Aspects of multilingual storage, processing and retrieval. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728998000133

- Green, D. W., & Abutalebi, J. (2013). Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(5), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2013.796377

- Grey, S., & Tokowicz, N. (2022). L1 and L2 vocabulary knowledge and language control in bilingual children. Journal of Child Language, 49(4), 801–823. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000921000274

- Jarvis, S., & Pavlenko, A. (2008). Crosslinguistic influence in language and cognition. Routledge.

- Jessner, U. (2003). A dynamic approach to language attrition in multilingual systems. In V. Cook (Ed.), Effects of the second language on the first (pp. 234–246). Multilingual Matters.

- Jessner, U. (2008). A DST model of multilingualism and the role of metalinguistic awareness. The Modern Language Journal, 92(2), 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00718.x

- Kroll, J. F., & Stewart, E. (1994). Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 33(2), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.1994.1008

- Kroll, J. F., & Tokowicz, N. (2005). Models of bilingual representation and processing. In J. F. Kroll & A. M. B. De Groot (Eds.), Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches (pp. 531–553). Oxford University Press.

- Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie, 45(3), 255–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0084295

- Prior, A., & Gollan, T. H. (2011). Good language-switchers are good task-switchers: Evidence from Spanish–English and Mandarin–English bilinguals. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17(4), 682–691. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617711000580

- Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 169–192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230

- Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2007). The shuffling of mathematics problems improves learning. Instructional Science, 35(6), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9015-8

- Swain, M. (2006). Languaging, agency and collaboration in advanced second language proficiency. In H. Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced language learning: The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 95–108). Continuum.

- Tulving, E., & Thomson, D. M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological Review, 80(5), 352–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0020071

- VanPatten, B. (2004). Input processing in second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing Instruction: Theory, Research, and Commentary (pp. 5–31). Erlbaum.

- Verreyt, N., Woumans, E., Vandelanotte, D., Szmalec, A., & Duyck, W. (2016). The influence of language-switching experience on the bilingual executive control advantage. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(1), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728914000352