Flashcards are one of the most commonly heard and widely used strategies for learning vocabulary. They're often recommended for a reason — spaced repetition is highly effective for memory consolidation. But they're not the only way to build a large and lasting vocabulary.

There are other interesting and scientifically supported strategies that I personally find more enjoyable and effective, and I'd like to share them with you here.

As a researcher in applied linguistics, a language teacher, and a lifelong language learner, I use these methods myself and also teach them to my students. They're grounded in science, based on how the brain actually processes, remembers, and uses language.

I speak six foreign languages (five of them at an advanced level). Like most learners, I started with flashcards. But for me, the process was painful. I used to write flashcards by hand, and while that deepened my memory more than digital tools, I kept losing them and often forgot the context in which the words were used.

Later, I tried digital flashcards. They were convenient, but because I often just copied and pasted definitions, I didn't process the words deeply enough. I also wasn't consistent in reviewing them, which made the effort feel wasted. With time, I collected a set of strategies that involve deep processing, emotion, context, and active use. They work far better for me.

Now, let me show you how you can build a 5,000+ word vocabulary without relying solely on the grind of SRS (spaced repetition software) decks.

But Why 5,000 Words?

Because research in corpus linguistics shows that knowing 3,000 to 5,000 of the most frequent word families gives you access to about 95% of everyday conversations and written texts (Nation, 2006; Webb & Nation, 2017). That's enough to read novels, follow podcasts, and participate in spontaneous conversations without constantly reaching for a dictionary.

5,000 words also marks the tipping point between B2 and C1 fluency. At this level, you move from a competent language user to a confident communicator.

It might sound like a lot, but it's surprisingly achievable:

- 10 new words a day = 5,000 words in just 17 months

- 5 new words a day = 5,000 in under 3 years

My Top 13 Vocabulary Learning Strategies

1. Use the Notebook of Curiosity (No Translations Allowed)

Instead of collecting disconnected translations, treat your vocabulary notebook as a living diary of language. When you hear or read a new word, write down the whole sentence it came in, ideally something personal, funny, emotional, or intriguing.

For example, instead of writing "whisper = susurrar", note: "Ella susurró algo, pero no la oí."

This approach uses elaborative encoding, which is shown to improve memory retention far more than shallow processing like translation (Kang, 2016). You're anchoring the word in a scene, emotion, or image and it becomes meaningful to your brain. Over time, your notebook becomes a personalized corpus of language that you processed deeply, which allows you to recall faster and longer.

Here are some quick tips how to use this strategy for best results:

- Revisit old notes weekly

- Add drawings, emojis, or color codes

- Don't translate, stay in the target language as much as possible

2. Learn Words in Stories, Not Isolation

Instead of memorizing word lists or disconnected example sentences, learn new vocabulary by embedding it in stories. The human brain is wired to retain narratives far better than isolated data.

Let's say you're trying to learn the word perro (dog). You could memorize the word and translation, or you could imagine:

Una señora caminaba con su perro pequeño, que llevaba un sombrero azul. Todo el mundo lo miraba.

Now you're not just learning perro. You're seeing the little dog, the silly blue hat, the people turning their heads. This multisensory input with characters, visuals, and emotions creates rich, interconnected memory traces.

Stories stimulate both the language-processing and experiential areas of the brain. Mar (2011) and Willingham (2004) found that narrative-based learning engages mental simulation and episodic memory, which makes vocabulary "stickier" and more retrievable.

- Invent simple stories that include the new words you're learning

- Read or listen to graded readers in your target language

- Picture each scene as vividly as possible to involve emotion and action

- Retell the story aloud or in writing with your own variations

3. Re-Read with Spaced Intervals

Rather than reviewing isolated words with spaced repetition software (SRS), return to meaningful texts you've already read and enjoyed.

For example, read a short dialogue on Monday. Skim it again on Wednesday. Revisit the same passage next week. Notice how your understanding deepens, how words become more familiar, and how new phrases pop out.

This method leverages the spacing effect. Re-exposing yourself to material at gradually increasing intervals dramatically improves retention and recall (Agarwal & Bain, 2019). When applied to meaningful context, like stories or dialogues, the effect multiplies because it activates both repetition and semantic encoding. Instead of rote flashcard flipping, you're reinforcing words through real language in rhythm, grammar, and emotional tone.

- Use short stories, dialogues, or podcasts you enjoy

- Highlight new words on your first read-through

- Reflect on what you understand differently during each reread

- Read aloud occasionally to strengthen pronunciation and retention

4. Listen More Than You Think You Should

Listening is one of the "laziest" and simplest ways for acquiring vocabulary, in my view. Yet it is powerful and brings good results. It's a no brainer — we need massive input to build a language base.

Listening is vital because even when you don't understand every word, your brain is working in the background — absorbing sounds, noticing intonation patterns, and connecting meaning through tone, repetition, and context.

Let's say you're listening to a beginner podcast where someone describes their day: "Me levanto a las siete. Me ducho. Desayuno pan con mantequilla." Even if you only know me levanto, repeated exposure helps you infer that ducharse and desayunar are also daily routines. Over time, the unknown words become familiar through recurring context.

This method draws directly from Krashen's Input Hypothesis (1985), which argues that language acquisition happens when learners receive comprehensible input — language that is slightly above their current level (i+1), but still understandable with context. The more you hear a word in context, the more deeply it gets encoded.

Recent neuroscience confirms this: auditory input activates broad areas of the brain responsible for both understanding and producing language (Skeide & Friederici, 2016). You're training your ear and your memory without even realizing it.

- Start with podcasts, graded audiobooks, or language YouTube channels that match your level

- Re-listen to the same audio to strengthen recognition and predictability

- Listen actively (with subtitles or transcripts) and passively (while walking or cleaning)

- Repeat aloud or shadow sentences to internalize rhythm and vocabulary

5. Talk Like a Child (and Be Proud of It)

Children don't wait for perfect grammar before they start using language. And you shouldn't either. One of the fastest ways to make new vocabulary stick is to use it actively, even if your sentences are simple, messy, or awkward. The goal isn't perfection. It's activation.

Imagine you just learned the Spanish word triste (sad). You could repeat it silently a dozen times… or you could start speaking aloud: Estoy triste porque no hay sol hoy. Mi gato está triste porque no tiene comida.

The moment you create your own sentences, you move from passive recognition to active use. You personalize the word, tie it to situations, and retrieve it from memory, which strengthens neural connections.

This taps into what researchers call the generation effect — a phenomenon where information is better remembered when it's generated by the learner rather than received passively (Karpicke & Aue, 2015). When you force your brain to retrieve a word and fit it into a sentence, you engage deeper cognitive processing and improve recall.

- Use new words in speaking or writing the same day you encounter them

- Narrate your daily actions using simple sentences (e.g., Estoy comiendo. Estoy caminando.)

- Record voice notes to yourself describing your day with your target vocabulary

- Be playful and expressive. Exaggeration, emotion, and fun help memory stick

6. Make It Personal and Emotional

You remember what matters to you, not what you're told to memorize.

One of the most powerful ways to make vocabulary stick is to connect it to your own experiences, feelings, and daily life.

Let's say you're learning the Swedish word trött (tired). Instead of just memorizing trött = tired, tie it to a sentence that reflects your real life: Jag är trött varje morgon klockan sex när Erik vaknar.

This is no longer just a translation. It's a snapshot of your daily routine, your feelings, and even your child's name. That makes it memorable.

This strategy works because emotional relevance enhances memory encoding. When a word is connected to something meaningful or emotionally charged, it triggers activation in the amygdala, the part of the brain involved in emotional processing. This, in turn, strengthens consolidation in long-term memory systems (Yonelinas & Ritchey, 2015). The more personal and emotionally engaging a piece of information is, the more likely your brain is to store it.

- Use new words to describe your actual thoughts, habits, and feelings

- Write journal entries or short texts using the day's vocabulary

- Choose example sentences that make you laugh, feel something, or tell your story

- Don't be afraid to exaggerate or dramatize. Emotion is a memory booster

7. Use Visual Anchors to Lock in Words

A single image can be more powerful than ten repetitions.

Our brains are highly visual, and when we associate new vocabulary with mental images, symbols, or even doodles, we engage a different and often more memorable memory pathway.

Let's say you're learning the word cuchara (spoon) in Spanish. Instead of just repeating the word, imagine a giant silver spoon dancing on your kitchen table. Or draw a quick sketch of your breakfast cereal with a cuchara in the bowl.

These images should be silly, huge, scary, or sexy for best results.

This strategy draws on dual coding theory, which states that information encoded both verbally and visually is more likely to be recalled than verbal information alone (Clark & Paivio, 2006). Visual and verbal processing activate separate neural systems in the brain, and when both are engaged together, memory consolidation is significantly strengthened.

- Create mental images for each new word. The weirder, the better

- Use color-coding or draw symbols in your notebook to represent categories of vocabulary

- Add images to your digital notes or use illustrated storybooks to reinforce meaning

- If you're artistically inclined, sketch simple scenes around your new words to help fix them in place

8. Learn Through Role Play and Simulation

Vocabulary sticks better when it's used in real-life situations or realistic simulations of them.

When you act out conversations, you bring language to life by engaging both your mind and body. This turns abstract vocabulary into something felt, experienced, and applied.

Imagine you're learning travel-related words in French. Instead of just reading billet, valise, and gare (ticket, suitcase, train station), act out a scene: You're in Paris. You're late. You rush to the ticket window and say, Bonjour, je voudrais un billet pour Lyon, s'il vous plaît. You mime holding a suitcase, checking the clock, running for the train. Now billet is a part of an experience you imagined, performed, and emotionally processed.

This method is supported by embodied cognition, showing that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body's interactions with the world. Glenberg et al. (2013) found that language retention improves when learners physically simulate the use of new words. Role play also taps into social and emotional learning, making vocabulary more accessible and natural in future conversations.

- Practice solo scenes: ordering at a café, checking into a hotel, calling a doctor

- Use props if possible (real menus, a toy phone, or your actual travel bag)

- Pair vocabulary lists with short scripted dialogues you perform aloud

- Record yourself acting out situations, then replay and repeat to reinforce fluency

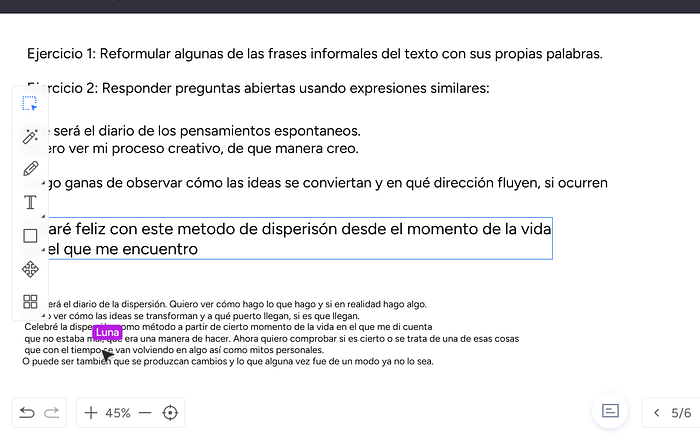

9. Paraphrase in Full Sentences

One of the most powerful ways to internalize vocabulary and deepen comprehension is by reformulating what you read, such as rewriting phrases using your own words and expressions. This forces your brain to actively process meaning, grammar, and nuances all at once.

When I was reading Metamorfosis by the Argentine author María Negroni, my Spanish tutor asked me to rewrite a paragraph from the original text using other words. We did it spontaneously during the lesson, without using the dictionary. My brain was exploding. It was so intense, creative, and unforgettable.

Here are some examples of what we did together:

Original: "Este será el diario de la dispersión." [This will be the diary of dispersion.] Reformulation: Este será el registro de mis pensamientos que aparecen de forma desordenada. [This will be the record of my thoughts that appear in a disordered way.]

Original: "Quiero ver cómo hago lo que hago y si en realidad hago algo." [I want to see how I do what I do, and whether I'm actually doing anything.] Reformulation: Quiero analizar mi proceso creativo y comprobar si realmente estoy produciendo algo. [I want to analyze my creative process and check whether I'm truly producing something.]

This exercise helped me activate and expand my vocabulary in a way flashcards never could.

This strategy draws on the power of elaborative rehearsal, which is shown to enhance long-term retention by requiring learners to retrieve and reprocess language in personally meaningful ways (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011). Reformulating engages both your receptive and productive knowledge trains you to think in the language.

- Choose thought-provoking sentences from poetry, prose, or articles

- Rewrite them using your vocabulary and tone, don't be afraid to be creative

- Speak your reformulations aloud to work on fluency and flexibility

- Do this regularly with a tutor or in a study group

10. Teach What You Learn

If you really want to remember a word, try teaching it to someone else. Explaining a new word out loud (to a friend, a study partner, your pet, or yourself in the mirror) forces you to retrieve the word, organize your thoughts, and clarify the meaning. This process is incredibly effective for deepening memory and comprehension. It is one of my favourites. Maybe because I am a teacher.

Let's say you've just learned the Swedish word lugn (calm). You could passively review it… Or you could try to explain it to someone like this:

"Lugn means calm, like when someone is relaxed and nothing is stressing them. For example, efter yogan känner jag mig lugn — after yoga, I feel calm. It's the opposite of stressed, which in Swedish is stressed."

That short explanation requires:

- retrieval of the word and meaning

- connection to examples

- contrast with opposites

- integration with your life

This method taps into what researchers call the protégé effect — the cognitive benefit learners get from teaching others. Studies show that learners who prepare to teach retain more information and perform better on assessments than those who only study for themselves (Fiorella & Mayer, 2013; Hoogerheide et al., 2016). Teaching activates metacognition: thinking about how you think and how you explain.

- After learning a few new words, try teaching them in your target language

- Record yourself giving a mini-lesson (1–2 minutes) using the words in context

- Share your explanations with a friend or on social media for accountability

- If you have no one around, teach imaginary students out loud. You'll still get the memory benefits

11. Use the Keyword Method and the Memory Palace

If you combine imagery, sound associations, and movement through space, you can create strong memory hooks, even for abstract or tricky words. Two of the most powerful mnemonic strategies for language learners are the Keyword Method and the Memory Palace.

The Keyword Method

This technique links the sound of a new word to a familiar word in your native language, then adds a vivid image that connects both meanings.

For example:

To remember caballo (horse in Spanish), you might think of the English word cab. Now imagine a huge horse pulling a yellow taxi cab through a busy street in Madrid. The funnier or weirder the image, the better. You've anchored the Spanish word caballo with an English sound cue and a visual image.

This method draws on dual coding theory (Paivio, 2006), which shows that when verbal and visual information are processed together, memory is significantly enhanced. It also supports phonological awareness, which is particularly helpful when learning unfamiliar sounds.

- Choose a keyword from your native language that sounds like the new word

- Create a vivid, silly, or emotional mental image linking the two meanings

- Picture the scene whenever you try to recall the target word

- Use this technique mostly for nouns or concrete verbs that are easy to visualize

The Memory Palace (Method of Loci)

Imagine walking through a familiar place — your home, school, or favorite café. As you mentally walk from room to room, you place new vocabulary words in each location using surreal, memorable images.

For example:

In your kitchen, a plátano (banana) is lying on your stovetop like a telephone. In your hallway, a libro (book) is sitting in your shoes, trying to walk. In your bathroom, a reloj (watch) is taking a shower and singing salsa.

This technique, dating back to ancient Greece and still used by memory champions today, allows you to recall dozens of words by mentally revisiting each "station." It leverages spatial memory, one of the strongest types of long-term memory in the human brain (Legge et al., 2012; Bower, 1970).

- Use places you know extremely well (your house, a friend's apartment, your morning walk)

- Place 5–10 new words along a route, each anchored by a striking image

- When reviewing, mentally walk through the place and "see" the words again

- Combine with spaced repetition to reinforce long-term storage

12. Connect New Words to What You Already Know

The brain loves connections.

New vocabulary becomes easier to learn when it links to something you already know. This could be a word in your native language, a word in another language you speak, a sound association, a root, a category, or even a personal experience.

For example, the Spanish word gato (cat) might remind you of the English cat — they sound different, but not entirely unrelated. If you speak French, you might also connect it to chat. If you're a visual learner, you might picture your neighbor's cat climbing onto your laptop, and associate that with gato every time you see one.

This strategy draws on schema theory, which suggests that new knowledge is integrated more effectively when it's built upon pre-existing mental frameworks (Kintsch, 2009). When you link a new word to familiar material, be it semantic (meaning), phonological (sound), or experiential, you reduce cognitive load and strengthen retrieval cues.

- Think about how the new word relates to something you already know

- Link it to a similar word in another language, a familiar root, or an emotion

- Use metaphors or categories (e.g., link lluvia to "weather words")

- Say the connection out loud or write it in your vocabulary journal to reinforce it

13. Group Words by Synonyms and Antonyms

One of the fastest ways to build a nuanced and expressive vocabulary is to group words by meaning relationships, especially synonyms and antonyms. Instead of learning a single word, you build a small, flexible network of similar or opposite terms. This helps you recognize shades of meaning and choose the right word in the right context.

Let's say you're learning the Spanish word feliz (happy). You could also learn:

- Synonyms: contento, alegre, entusiasmado

- Antonyms: triste, deprimido, enojado

Now you're not only understanding feliz, but also how it compares and contrasts with related words, which improves comprehension, recall, and expressive fluency.

This strategy is supported by research on semantic mapping, a vocabulary technique that improves word retention by organizing terms into meaningful categories or relational groups. Studies show that learners who group words semantically perform better on vocabulary tests and use more varied language (Schmitt, 2008; Liu & Nation, 1985).

- Create word webs with a central term and radiating branches of synonyms and antonyms

- Use the new words in short contrastive sentences: Estoy contento hoy, pero ayer estaba muy triste. (I'm happy today, but yesterday I was very sad.)

- Sort your vocabulary notebook by themes and subthemes (e.g., emotions: positive vs. negative)

- Practice explaining the subtle differences between similar words

Final Thoughts: Learn Like a Human, Not a Machine

You don't need to force yourself through endless flashcard decks to build a powerful vocabulary. Flashcards can be useful, but they may feel lifeless, rigid, or disconnected from real communication.

Language isn't a static list of words. It's movement, memory, emotion, context. It's stories, images, experiences, habits, and self-expression.

The 13 strategies I've shared in this article come from my life as a language learner, a teacher, and a researcher. They've helped me reach fluency in multiple languages.

If one method doesn't resonate with you, try another one. Make your own personal toolkit that fits your learning style, your goals, and your personality. You just have to learn in a way that your mind loves to remember.

Practice consistently and connect deeply with your new words.

Because you can learn 5,000 words (and more ) without ever touching a flashcard app.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this article, leave a comment and follow for more research-based insights on language learning, fluency, and mindset.

References

Agarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching: Unleash the science of learning. Jossey-Bass.

Bellezza, F. S. (1996). Mnemonic methods to enhance storage and retrieval. In E. L. Bjork & R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Memory (pp. 345–380). Academic Press.

Bower, G. H. (1970). Analysis of a mnemonic device: Modern psychology uncovers the powerful components of an ancient system for improving memory. American Scientist, 58(5), 496–510.

Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (2006). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149–210.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2013). The relative benefits of learning by teaching and teaching expectancy. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(4), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.06.001

Glenberg, A. M., Witt, J. K., & Metcalfe, J. (2013). From the revolution to embodiment: 25 years of cognitive psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(5), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613498098

Hoogerheide, V., Loyens, S. M. M., & van Gog, T. (2016). Learning from video modeling examples: Content expertise is more important than physical similarity. Learning and Instruction, 44, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.006

Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

Karpicke, J. D., & Aue, W. R. (2015). The testing effect is alive and well with complex materials. Educational Psychology Review, 27(2), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9309-3

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Kintsch, W. (2009). Learning and constructivism. In S. Tobias & T. M. Duffy (Eds.), Constructivist instruction: Success or failure? (pp. 223–241). Routledge.

Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Longman.

Legge, E. L. G., Madan, C. R., Ng, E. T., & Caplan, J. B. (2012). Building a memory palace in minutes: Equivalent memory performance using virtual versus conventional environments with the Method of Loci. Acta Psychologica, 141(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.09.002

Liu, N., & Nation, I. S. P. (1985). Factors affecting guessing vocabulary in context. RELC Journal, 16(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368828501600103

Mar, R. A. (2011). The neural bases of social cognition and story comprehension. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 103–134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145406

Nation, I. S. P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.63.1.59

Paivio, A. (2006). Mind and its evolution: A dual coding theoretical approach. Psychology Press.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 329–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168808089921

Skeide, M. A., & Friederici, A. D. (2016). The ontogeny of the cortical language network. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(5), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.23

Willingham, D. T. (2004). The privileged status of story. American Educator, 28(2), 43–45.

Worthen, J. B., & Hunt, R. R. (2011). Mnemonology: Mnemonics for the 21st century. Psychology Press.

Yonelinas, A. P., & Ritchey, M. (2015). The slow forgetting of emotional episodic memories: An emotional binding account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(5), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.02.009

My Friend retro games NES SEGA