RETROCOMPUTING

The modern cockpit is full to the brim with advanced technology. But back in the day computers had only made small inroads into the lives of pilots.

This is another old article pulled from the archives, and again with an aviation theme. This one was written for Pilot magazine in the UK and was published, I would guess, in 1991 (I got my Private Pilot's Licence in 1990).

Pilots have long been enthusiasts of the latest technology. For example, we were using GPS long before it showed up in cars. (And sometimes misusing it to go to the wrong place with stunning precision.) Multifunction LCD displays replacing the old 'sixpack' of steam-driven instruments are now found even in humble Cessnas and professional pilots don't go anywhere without their 'digital flightbags' (what most of us would call an iPad).

However, at the time I wrote this piece, computers were nowhere to be seen in light aircraft and were even a rare sight in flight schools. Private pilots might run a copy of Microsoft Flight Simulator on a home PC to keep their skills from atrophying over the winter months, and flight planning software was available, although expensive, limited and mostly owned by those of us who were also geeks.

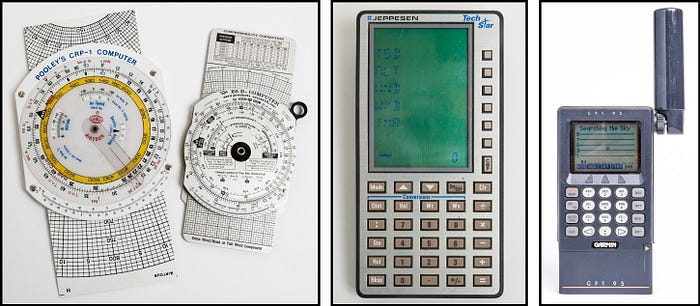

You would get your weather reports by fax. And while, if you were being fancy, you might calculate your cross-country flight headings, flight time and fuel burns with a special electronic calculator, you were just as likely to do it with a circular slide rule, commonly dubbed the 'whizz wheel'.

Modern technology has made flying easier and safer. But I also have a nostalgic fondness for the pre-computer cockpit.

And I still occasionally pine for the old days of the Bulletin Board System (BBS) and CIX. And yes, I'm aware that there are BBS hosts still going, reachable over Telnet. And yes, I know that CIX is also still going. But it's not the same. Back then, these systems were the only way of reaching out over the wires to other people and other places. They were almost magical ways of transporting yourself to virtual worlds. Now they're just a difficult way of doing something that's better and more easily achieved by other means. That said, I think I might go log on to a BBS or two…

BULLETIN BOARDS FOR PILOTS

You just can't get away from computers. They sit in the laps of well-equipped navigators. They will even simulate flying on the days when the weather has other ideas. But have you ever thought of using a computer to chat with other pilots, swap information, buy or sell planes or even look for a job?

All this is possible simply by hooking up your home or office micro to the telephone network so that it can talk to other computers. There are hundreds of commercial 'online' systems, offering electronic mail services and specialised databases. But of most interest to pilots are the few bulletin boards run by aviation enthusiasts for like-minded people.

A bulletin board system (BBS) is just as it sounds — a place where people leave messages for others to read. By linking your micro to the BBS host computer you can read or write public messages, send or receive private mail, read articles and stories left by other people, and even receive computer programs through a process known as downloading — all without leaving your office.

Follow the instructions

It's a lot easier than it sounds. You need a piece of hardware called a modem (see box copy) and some suitable software, but after that it's a matter of ringing the phone number of the system you want and letting the software do the rest. You don't have to know much about how the system works — just follow its instructions.

The system operators (or 'sysops') are generally enthusiasts doing it for love. Most bulletin boards are free to users — at most, you might be asked to send a once-only joining fee to help defray the sysop's costs.

The leader among free aviation-based systems is Airtel, based near Gatwick. Its location gives a clue to the occupation of Adrian Pop, its sysop. In his free time, when he's not staring at a computer monitor, Adrian is to be found staring at the instruments of a BAC-111, which he flies for BIA.

Airtel was started in January 1986, with the intention of being aviation-only. It has since widened its scope, but Adrian still regards aviation as its most important area. As well as interesting (and sometimes hairy) stories by pilots, the board carries information about gliding clubs and the opportunity to put yourself to the test with multiple-choice ARB exams.

Adrian is helped by four other enthusiasts, each running a section of the board. One of these co-sysops, Dan Butterworth, has now set up his own board, called Runway. Dan is a fixed wing and helicopter PPL, and is aiming to become an instructor, although he's meeting with resistance due to his age — he's only 17!

He set up Runway primarily as a way of getting in touch with other people who share his interest in aviation. Links are being established with several boards in the USA, plus Singapore and Australia, providing automatic transfer of mail and selected messages.

Runway started up at the beginning of August and so is still fairly bare. Dan is adding articles and software as fast as he can, but is open to offers, and all contributions are gratefully accepted.

A forum for people

The health of a bulletin board is directly proportional to the contributions of the people who use it. Unlike a commercial database, which provides information to be plundered — at a price — a BBS is meant to be a forum, with the users supplying the information and entertainment, while the sysop keeps the system running and checks that things don't get too out of hand.

This principle has been taken a stage further by CIX (pronounced 'kicks'), or Compulink Information eXchange. As with bulletin boards, the messages are divided into subject areas, or 'conferences', often further divided into specific topics. The difference is that these are not fixed by the sysop. Anyone can start a new conference and become its moderator, deciding who can join in, who to throw out and what direction the conversation should follow.

The software CIX uses is also rather more sophisticated than the average BBS. It knows which messages you have seen, and presents you with only the unread ones. There are excellent private mail facilities, and, whereas most boards run on a single phone line (which is usually engaged!) CIX has multiple lines. There are usually around a dozen people online at any time, and it's possible to 'chat' with other users — anything you type will be printed on their screens but isn't available for general viewing.

The principle difference between CIX and other boards, however, is that CIX is not free. There is a joining fee plus charges based on the amount of time you use the system, with a minimum each month of £5 (plus VAT). I use the system quite a bit and rarely exceed the minimum.

Joining is easy enough. You simply log-on as a new user and quote a credit card number. You'll be asked for a nickname, to identify yourself and to be used by other people for addressing mail. Mine is 'Rotsky', so if you do join send me a message to let me know.

At the time of writing, the two aviation conferences were fairly moribund; CIX tends to be overloaded with computer types who have little to say about other subjects. But if a few more pilots and aviation enthusiasts get on to the system, it could become interesting again.

FlightStar

Like most things to do with computers, the system used by CIX originated in the States. The bulletin board scene, like general aviation, is much healthier over there. There are around 25 aviation boards, of which perhaps the most interesting is FlightStar.

There are two levels to FlightStar. Getting access to the full facilities involves paying a monthly subscription plus time charges, but many areas are free. .pa FlightStar is aimed at the aviation trade as much as the private pilot, and is unusual among bulletin boards in having fully interactive databases available online. These include a list of missing aircraft, used extensively by law enforcement agencies, lists of aircraft for sale, provided by a leading broker, and job vacancies.

The sysop, Mickey Russell, is planning to add more databases, including the Aircraft Information Guide, along the lines of Jane's, and a Blue Book-type guide to aircraft prices.

And it is expanding in other ways. The US operation is currently based in Houston, but is moving soon to a larger system in Denver, which can be accessed using existing US data networks.

European and Far Eastern branches should be opening soon — indeed, a UK operation was attempted recently by Dan Butterworth but foundered due to disagreements between him and Mickey Russell. It's not certain whether the next attempt will be based in the UK; apparently there's a lot of interest in Germany. Australian branches in Melbourne and Sydney are also on the cards. The systems will be fully linked, so that messages on one board will be available on the others.

I've used bulletin boards to set up aircraft photography sessions and find information. It's a great way to seek help and find friends.

[BOX COPY]

WHAT YOU NEED

The UK's stone-age phone system is incapable of handling computer signals, so a device called a modem (modulator/demodulator) is needed. These work at various speeds, measured in baud. The best general purpose speed is 1200 baud, although 300 baud is useful when you have a rough phone line, as there's less risk of data corruption. The better modems operate at a variety of speeds, but whatever you get should have these two at least. Most recent modems are sophisticated beasts capable of dialling numbers for you. But make sure you get software which is capable of operating these features. Fortunately there is an industry standard of a sort, called the Hayes command set. Modems and software capable of handling Hayes commands will work together.

The three software packages which I can recommend are Procomm Plus for IBM PCs and compatibles (with Mirror II coming in second), Fastcomm for the Atari ST, and Modem Master for the BBC micro.

And there is one other crucial item — money. Even with the free systems you'll be spending a lot of time on the phone. If you don't monitor your time the quarterly phone bill could be a shock from which you'll never recover.

This is part of an ad hoc collection of features drawn from an archive of articles I wrote, as a jobbing freelance journalist, for UK computer magazines in the late 1980s and early-to-mid 90s, and for which I retained the copyright. I have not amended the text, so any original errors remain.

You can find all the archive articles here.

Steve Mansfield-Devine is a freelance writer, tech journalist and photographer. You can find photography portfolio at Zolachrome, buy his books and e-books, or follow him on Bluesky or Mastodon.

You can also buy Steve a coffee. He'd like that.