RETROCOMPUTING

History isn't just about dates and the events that get memorialised in plaques and statues. Far more fascinating is the personal and the quotidian. A thumbprint left in an ordinary ceramic bowl is a more direct connection to the lived experiences of people the past than any number of crowns and sceptres.

And I think there's an aspect of even recent history that we can easily overlook. In the story of how computers have evolved, for example, it's too easy to get concerned only with the technology — and its occasional quaintness — and miss how the developments in data processing impacted lives.

What inspired this philosophical diversion is a package I received from my dear friend Doug — artist and sage. The package contained a small archive of documents belonging to his father, who is sadly no longer with us.

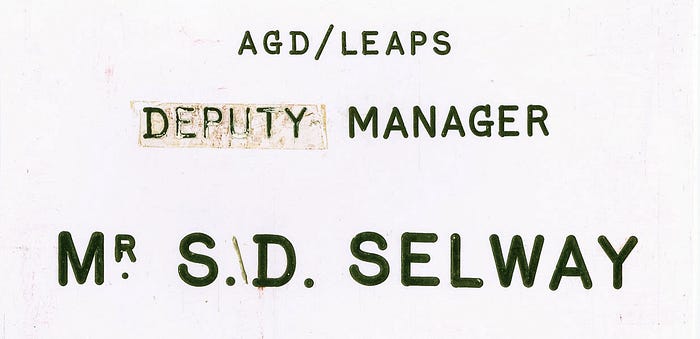

SD Selway — known to most, including the many people who loved him, as Big Doug — worked for the GPO, the UK's nationalised postal service which also provided the country's telephone, telex and other communications services. He'd worked his way up, via service to his country in the Signals Corp, from being a 'boy messenger' to, at the end of the 1950s and into the 1960s, being the manager in charge of the London Electronic Agency for Pay and Statistics (LEAPS) computer centre, part of the Accountant General's Department (AGD).

Elliott computers

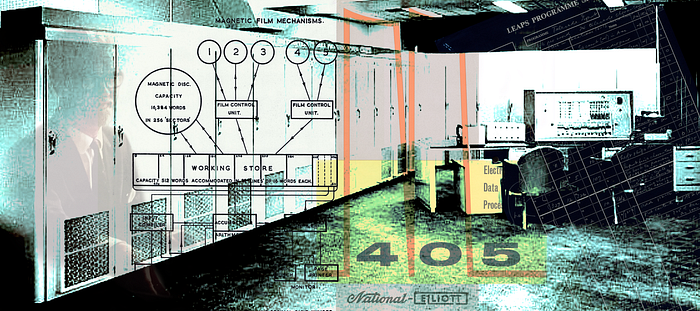

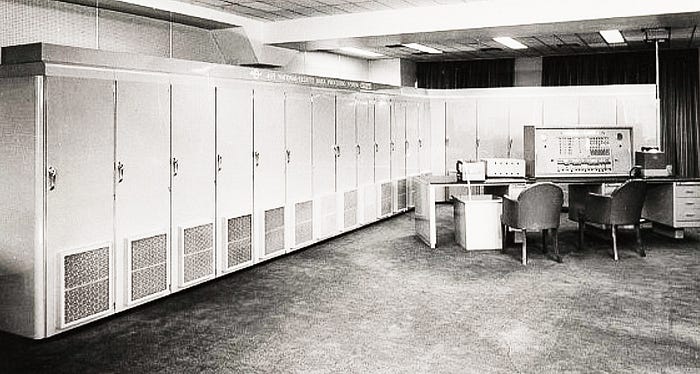

The LEAPS operation ran not one but two National-Elliott 405 computers for managing payroll and generating statistical data.

Elliott Brothers was a highly influential firm in UK computing history. It would, through later splits and mergers, form important parts of both ICL and GEC. At the time the LEAPS machine were installed, the firm had been acquired by National Cash Registers (NCR) which was reorienting itself as a computing company.

The National-Elliott 405, released in 1956, was the pinnacle of the 400-series, which started with the 401. Like all computers at the time, it was a valve-driven, room-hogging monster which used 33-bit words (one bit was used for parity).

The technology looked very different from what we're used to today. For example, immediate storage was provided by nickel delay lines. Essentially, bits were encoded in a looped length of wire by twisting it — a process dubbed magnetostriction. The twist (representing a bit) worked its way along the wire to be read by a sensor at the far end.

Delay lines had some similarity to the modern dynamic RAM (DRAM) that's in your computer now. It constantly needed refreshing. As each twist (or non-twist) worked its way out of the end of the wire, you had to write it back to the start again, assuming you didn't want to change that value in memory. (Another common form of delay line used audio pulses running through long tubes of mercury.)

The bits flew around the wire at a rate of 600 times a second. Each wire could hold just one word of data, so we're not talking about gigabytes here. As far as I can work out, the delay lines were used for something akin to what we would think of as stack memory today or perhaps the registers in CPUs.

Unlike modern DRAM, delay lines were not random access. To read a word, you had to wait for the start of it to come around in the refresh cycle.

You couldn't put enough data into the delay lines to use them the same way we use RAM now. For that, you'd turn to the 8½in magnetic drum.

And for persistent storage there were 19¼in magnetic disks and tape — the latter being 1,000ft reels of mag-coated 35mm film. A reel could hold around 300,000 words of data in 64-word blocks. The disks were smaller, holding either 16,384 or 32,768 words, again in 64-word sectors. And the drum was smaller still — at 4,096 words.

A couple of these machines are now preserved as museum pieces. There's a great piece of footage showing a 405 being installed at Reckitt & Sons, manufacturers of cleaning products, in Hull, 1959. It features lovely old lorries, men in white coats and more health & safety violations than you can count. The film is silent, but I'm sure you can provide your own Mr Cholmondly-Warner voiceover.

What's in the package?

The archive is small but fascinating. There's a brochure for the Elliott 405; a quaint eight-page booklet entitled An Introduction to Binary Arithmetic; and a small, folded cheat sheet giving stats about the 405 and a list of its opcodes — which aren't many.

There's also a copy of the March 1959 issue of Automation and Automatic Equipment News magazine. This includes a surprisingly long article about the LEAPS computers — surprising because they hadn't yet been installed and also because the article is essentially a report of a meeting. Yet it contains some real gems of information — not just a few technical nuggets but also a fascinating insight into the concerns about machines taking people's jobs and deskilling work (the meeting was attended by, among others, representatives of trades unions). This is even before the 1960s had steamrollered into view.

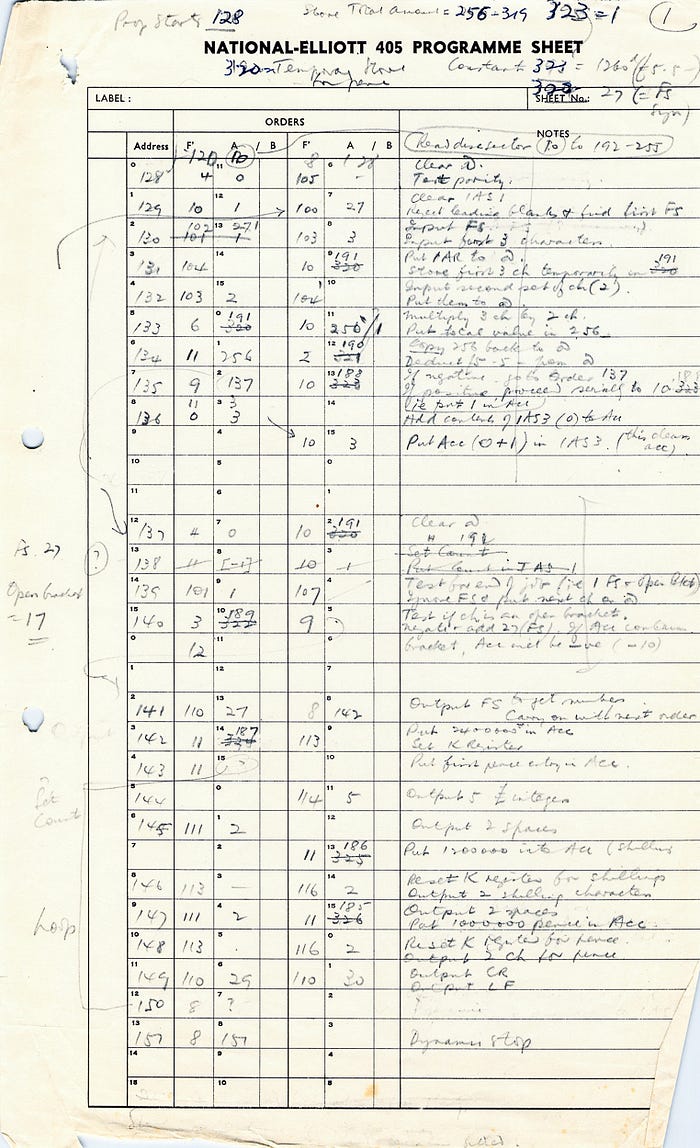

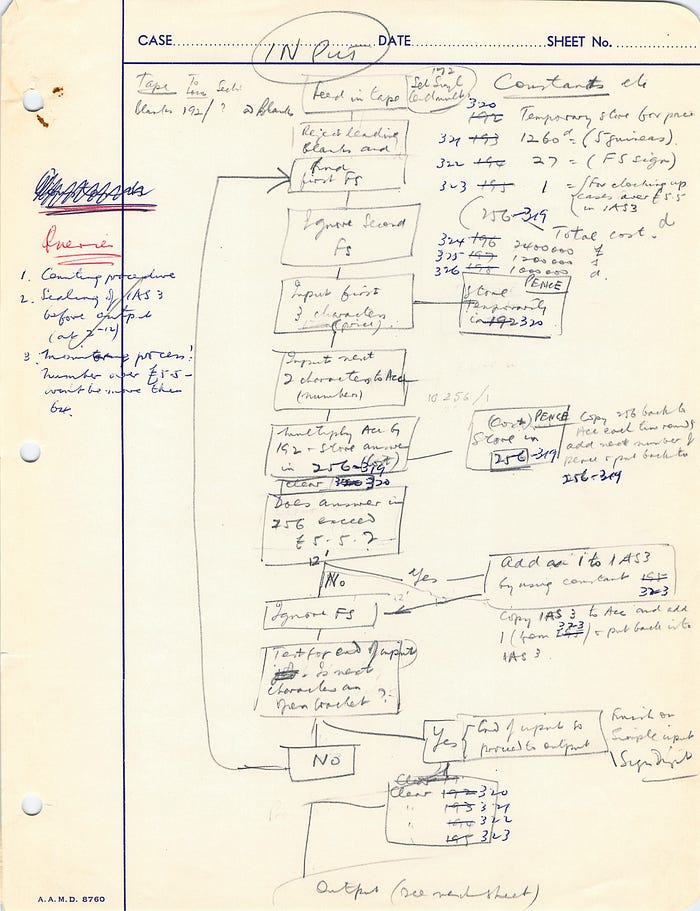

Most interesting of all, to me, are pages of notes that appear to be Big Doug working on programming problems — getting to know the machine and how to use it. These are all handwritten. Some are labelled as 'revision' exercises and may actually have been exams of some sort (on one sheet he admits to having run out of time).

What you can see on these sheets — many of which are custom programming sheets for the Elliott 405 and contain code — is someone learning, taking on board the new ways of thinking that came with the digital age. There's that direct connection here with the human experience that is so often missing from more artefact-focused histories of computing.

Along with the documents, the package contained one very intriguing piece of 5-bit punch tape. What's on it? Who knows?

Pitiless clarity

Finally, there is a delightfully yellowed piece of paper on which someone (Big Doug?) has typed out a quotation. It's from the book Electronic Business Machines edited by Joseph Harry Leveson (not 'Leverson', as typed) and published by Heywood & Co, London in 1959.

It says:

"Indeed, no attribute of the electronic computer is more startling than the pitiless clarity with which it exposes, and proclaims, the capabilities and shortcomings of those concerned in its use."

Well, nothing much has changed, has it? Pitiless clarity is still the computer's greatest power.

Let's look at some of the other documents in more detail.

Elliott 405 — basic principles

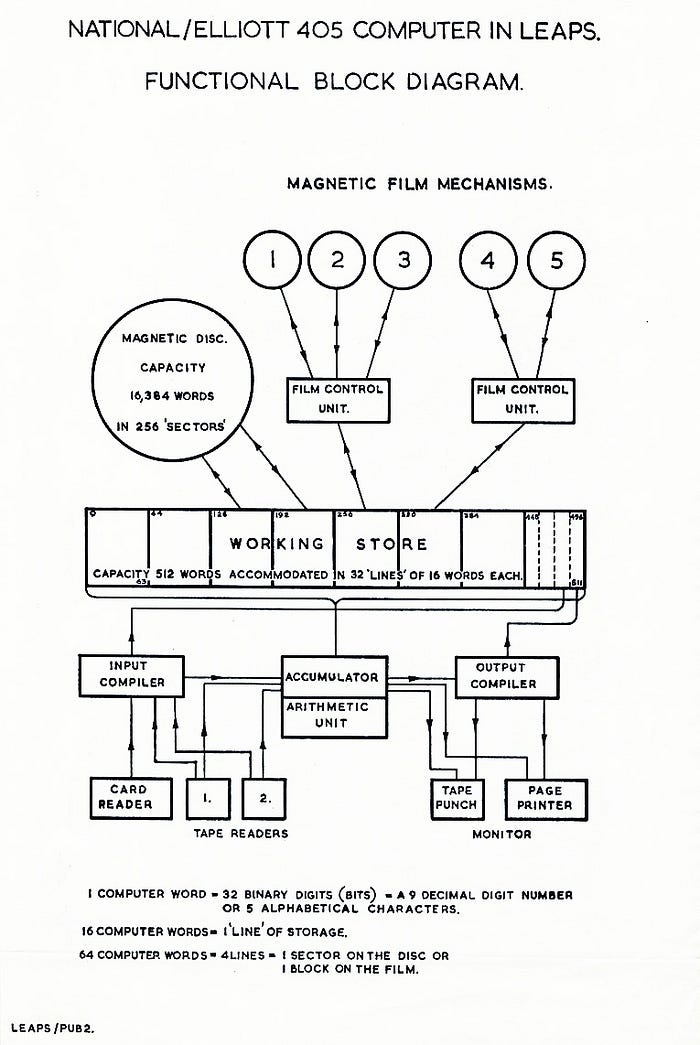

First up is a 'functional block diagram' of the system. And what I find interesting about this is:

- How basic it is. Computers were really quite crude beasts back then.

- How it was felt you needed to know this stuff. Of course, you've always needed to know this kind of detail when working with 'big iron'. The commoditisation of computing hardware extends only so far up the food chain. But this is real hands-on computing.

This document was produced by LEAPS and so was presumably aimed at employees who were actually working directly with the machine.

In a similar vein, we have a typewritten document — I suspect put together by Big Doug himself — providing an even more basic introduction to what computers are and how they work. Alas, Big Doug is no longer around to explain why he wrote this brief but succinct overview. But one can hazard some speculation.

Computers were still new and alien things back in June 1958 when this document was written. Some people were afraid of them. Some were confused. Most were (understandably) ignorant. Perhaps Big Doug felt that a little bit of demystifcation was in order.

Here's the text:

D.17.6.58

The Basic Principles of Computers

Computers for office work are automatic electronic machines which take in information and subject it to a variety of arithmetical and logical processes to produce wanted results. Much of the input information, or data, is numerical; inside the machines numbers are represented by groups of electrical signals, and the machines are called digital computers because a separate signal is used for each digit.

Electronic machines use radio valves, transistors, resisters, capacitors and similar components of the sort that are to be found inside a television set. Electronic computers are fast and accurate; thus, the LEAFS computer can add two 10-digit numbers together in 1/6000th of a second.

The automatic nature of a computer enables it to undertake, without any human intervention, long sequences of connected operations, by passing the results of earlier operations on to subsequent operations, and by using the intermediate results to select which of alternative sets of operations shall follow.

For their arithmetic most computers use binary numbers as these have only two different digits, 0 and 1, to be represented by electrical signals instead of the ten of decimal numbers. Binary numbers look strange at first, but are built up on a similar plan to decimal numbers thus, 11010 is the binary representation of 26 as, no units, one two, no fours (2 x 2), one eight(2 x 2 x 2) and one sixteen (2 x 2 x 2 x 2). Binary arithmetic is identical with decimal arithmetic, and the computer is arranged to convert automatically between the binary and decimal scales.

The computer performs its arithmetic by combining and selecting the groups of signals that represent the input numbers in ways that produce another group of signals that represent the required answer.

A.1519W.200.5.60.AA

Brochure: Elliott 405 — a simplified representation

There's something about this brochure that just screams 1950s. The graphics on the cover, for instance, are straight out of Mad Men.

'A simplified representation of the National-Elliott Electronics Data Processing System' is the kind of brochure you wouldn't think was necessary — or appropriate — for this kind of machine. The Elliott 405 wasn't something you bought on a whim, or while intending to shop for a new stereogramme.

Purchasing a mainframe computer of this kind usually involved committees, exploratory talks and months of negotiations. What part a six-page brochure would play in that process is hard to fathom. And yet, there it is, in Big Doug's stash of documents from his days at the GPO.

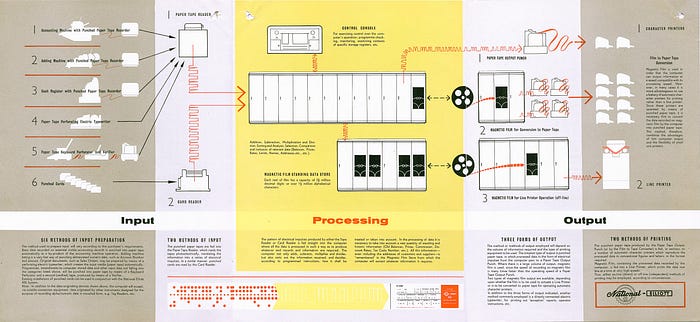

Once folded out, the main three-page spread provides an overview of the 405's capabilities — input on the left, processing in the middle and output on the right.

This is logical enough. But I also like the way it (more or less) echoes the von Neumann architecture.

Input: It lists lots of input sources, including accounting machines (whatever they are) and cash registers. The 'National' in National-Elliott comes from National Cash Registers, after all.

Ultimately, though, everything goes via a paper tape reader or a card reader. There's no mention of teletype input. And this reflects the intended purpose of this kind of machine. Note that it's referred to as an "Electronic Data Processing System". EDP was the buzz term, rather than 'computing'. So while the Elliott 405 may have been Turing complete, its range of applications was seen in fairly narrow terms — primarily number crunching for the accounts department.

Processing: The processing page details what the machine can do with your input — namely: "Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication and Division; Sorting and Analysis; Selection; Comparison and inclusion of relevant data (Balances, Prices, Rates, Limits, Names, Addresses, etc, etc)."

Yup, that sounds like accounting alright.

It also mentions (per von Neumann) storage — via 35mm mag-coated film.

Output: When it comes to getting stuff out of the machine, we're really spoiled, with no fewer than three options — paper tape, film to paper tape conversion and line printer. Heady stuff.

Beyond invoices

Actually, I've probably been a little unfair to the Elliott 405 in suggesting that it's largely a glorified calculator for spitting out invoices and receipts.

The 'general notes' page gives hints about other applications:

Whether an Electronic Data Processing System is installed principally for the purpose of mass-producing Documents of Commerce and essential internal records, or whether it is installed according to a more sophisticated programme to incorporate the provision of accurate "stop-press" information for the purpose of scientific management and policy determination, the system will only afford its greatest benefits if it is designed expressly for the purposes of processing business data.

It then goes on to boast of the 405's three levels of data storage that make the machine so ably designed for these functions — including 512 words of high-speed memory, the 16,384 words of intermediate storage on magnetic disk and the longer term storage on magnetic film.

I'm still not sure what "stop-press" means, though.

Cheat sheet

In among Big Doug's small but treasured trove is a small yet fascinating document that seems to be part cheat sheet and part marketing material.

The six-page, fold-out booklet is handily sized to fit into a shirt pocket, along with your pocket protector and 6H pencil.

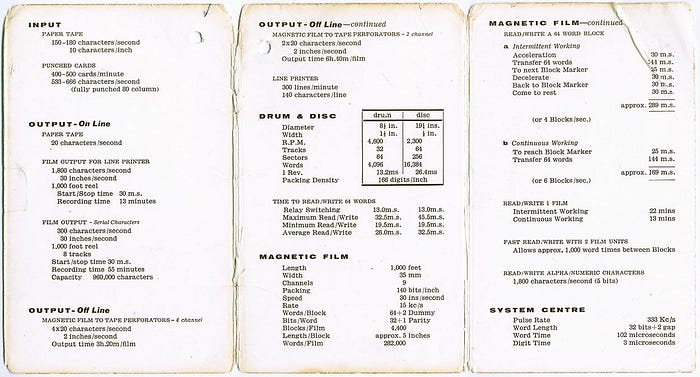

Most of the National-Elliott 405 Basic Information document is taken up with specifications. We're told, for example, that the machine can output to paper tape at the blistering rate of 20 characters per sec. Things get faster when writing to film (that is, mag-coated 35mm film in 1,000ft lengths). That happens at 300 characters per second, or 1,800 when transferring from film to line printer (at least, that's how I read it).

Film is not the only storage medium. There's also an 8½in drum and 19¼in disc (note, 'disc', not 'disk'). The former spins at 4,600rpm and the latter at a still respectable 2,300rpm. The drum is capable of storing 4,096 words and the disc 16,384. And the average time to read/write 64 words is 26ms for the drum and 32.5ms for the disc.

None of this is going to worry today's Seagate or Western Digital much. Storage speeds are always a touchy matter, with so many factors at play. But let's say that an NVMe drive might do sequential writes at 5,000MB/s. That's 40,000 Mbits per second. Put another way, it's 40,000,000,000 bits per second.

The 405 is writing 64 33-bit words in 26ms for the drum. (I'm giving it the benefit of the doubt in assuming the parity bit is saved.) By my math, that's 81,230 bits per second. So, a slight difference. And I know there's a lot to argue about in those numbers, but we're just having fun here and a speed increase of nearly 500,000 times is worth having.

Instruction set

The other pages of the leaflet are taken up with what appears to be the Elliott 405's instruction set — or 'O-Code Instructions'. There's not a lot to them.

There are just 15 instructions (helpfully numbered 1–15), eight of which do basic maths operations on what appears to be a single accumulator.

Three instructions relate to 'jumps' — ie, conditional or unconditional branching. And two allow you to move data from a storage location.

This is reduced instruction set computing (RISC) at its finest. Move over 6502. Eat my dust ARM.

The booklet is well-thumbed. I can just imagine Big Doug having this on his desk as a reference while scribbling furiously with a pencil as he mapped out his first programs.

Why this might seem a paucity of instructions, remember that the function of the LEAPS 405 machine was to handle payroll — that is, to calculate and collate fairly simple numbers. No-one was doing any fast Fourier transforms or 3D modelling with these beasts. Nor were they trying to run Crysis.

It might be fun to try writing a usable program with just these opcodes. Any takers?

All the documents are available to download as PDFs via my GitHub repo.

[UPDATE 04/06/2025]: The PDFs have now been fixed. There were problems with the initial uploads.

Resources

- Elliott Brothers (computer company), Wikipedia.

- Systems Architecture for Elliott 401, 402, 403 & 405 computers, DJ Pentecost (PDF).

- Installing of a National 405 computer at Dansom Lane. A film (no audio) documenting the installation of a National-Elliott 405 at Reckitt & Sons, Hull in March, 1959. Yorkshire Film Archive/North East Film Archive.

- Tomorrow's World: Nellie the School Computer. Forrest Grammar School in Winnersh was donated a 405, which the schoolboys got to operate — for a while. It was scrapped in 1971 with only one delay line surviving (see link below). You can see a faulty delay line being swapped out in the film. BBC, 15 February 1969. YouTube.

- Elliott 405 Nickel Delay Line from "Nellie".

- A 405 at the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, NSW, Australia. MAAS.

- Framboise 314. A drole comparison between the Elliott 405 and a Raspberry Pi. It's in French, but if you don't read the language you can always enjoy the pictures.

Steve Mansfield-Devine is a freelance writer, tech journalist and photographer. You can find photography portfolio at Zolachrome, buy his books and e-books, or follow him on Bluesky or Mastodon.

You can also buy Steve a coffee. He'd like that.