RETROCOMPUTING

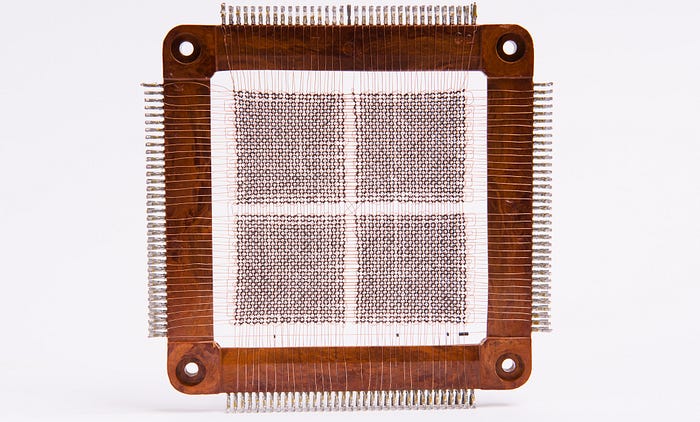

There are some things that are hard to get your head around unless you can actually see them. Being a computer history fan I've often read of core memory but never quite got to grips with how it works. So one day I just thought, 'the hell with it — I'll go on eBay and buy some'. Which I did.

According to the seller's description, the single plane of memory I was sent was taken from a 1960s Soviet Saratov-2 (Саратов-2) minicomputer, a clone of the DEC PDP-8/M. Allegedly, the Soviets nabbed a PDP from a sunken US submarine and the computer was then reverse engineered by the Central Research Institute of Measuring Equipment (ЦНИИИА), in the city of Saratov. I'm taking all this on faith. I haven't yet found much info online about this machine other than a thread in a Russian-language forum. Chrome has done it's best to translate this for me, bless, and provided hours of amusement in the process.

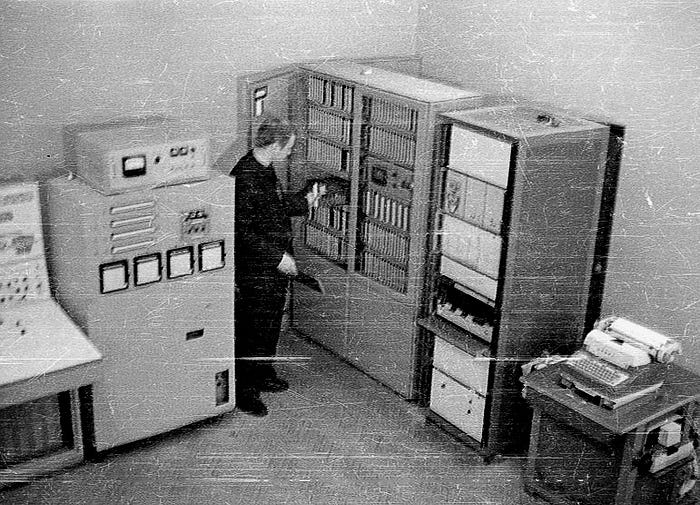

The forum also has a number of intriguing images, including this one claiming to be a Saratov-2.

It's generally referred to as a 'control' computer, so I assume it was used mostly in scientific and industrial environments.

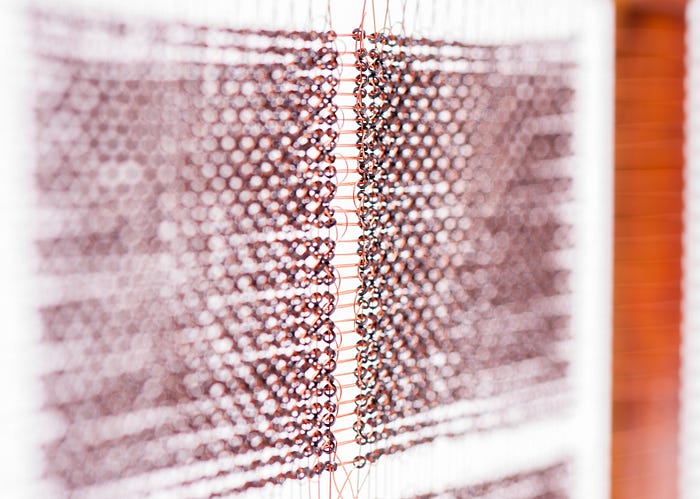

I'm not sure why a handful of the cores on my device are off to one side with only one wire going through them, but hey ho — I bought this for a handful of dollars as an objet d'art, not a piece of technology I plan to use.

The plane has 64 x 64 cores, and so is capable of holding 4096 bits of data. The PDP-8 was a 12-bit machine so it would have had 12 (or multiples of 12) of these core planes. The 12-bit word would have been spread across the 12 planes, one bit being stored on each. So, with 12 planes, you'd get 4K (words) of memory.

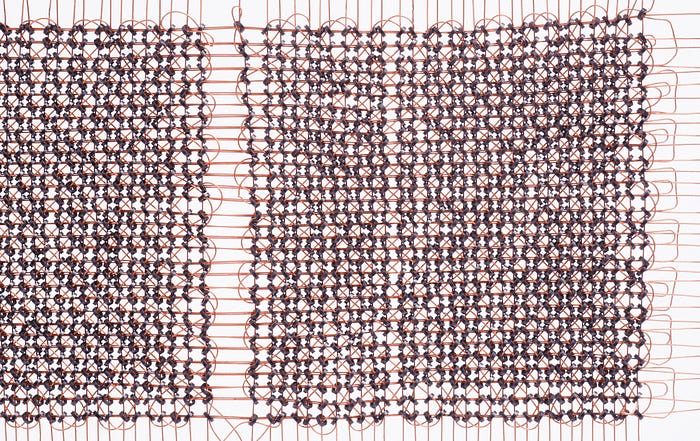

Core memory first came into use in the 1950s. It employs small rings (cores) of ferrite through which wires are laced. They're called cores because the technology developed out of transformers, where wire is wound around a ferrite core.

Ferrite (at least if you have the right kind) has the property that, if it is exposed to a magnetic field in a certain way, it will itself become magnetised. A magnetic field operating in the opposite direction will 'flip' the polarisation of the magnet, if it was previously set.

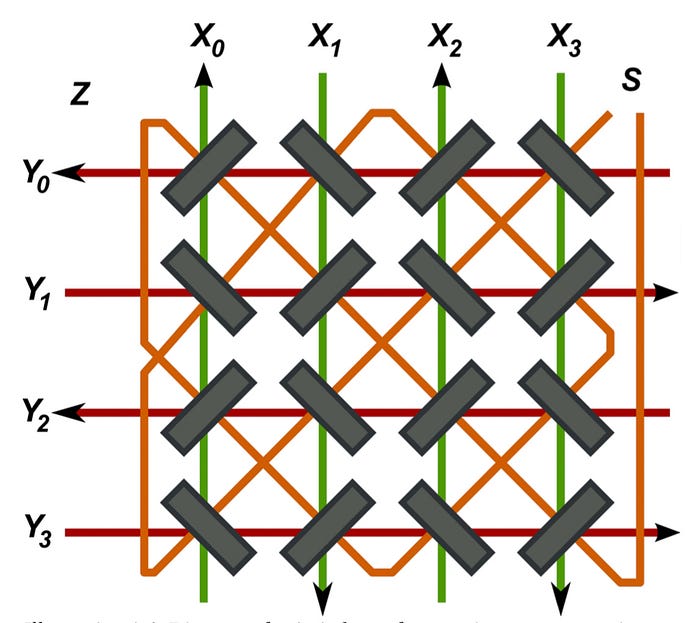

Here we're talking about X/Y coincident core memory. There are, apparently, other types.

To create this magnetic field, you run a wire through the core and send a current down it. To create the opposite field, send the current the other way (ie, switch polarity).

To create a memory bank, you arrange the cores in a matrix. You run X and Y wires (drive lines) through them. Let's say you have a matrix of 8 x 8 cores. Each X wire and each Y wire will run through 8 cores. To select a specific core, you put half the current required to affect the core through its X wire and half through its Y wire (a logical AND). That way, only one core — where the wires intersect — has enough current to be affected. By selecting which direction the current runs through the wires, you can flip a core 'on' or 'off' (or 1 and 0, although all these labels are just conventions we impose on the magnetic state).

To read the state of the cores, you thread a single 'sense' wire through all the cores. Select the relevant X and Y wires for the core you want to read then energise those wires, with the current flowing in the opposite direction used for writing — in other words, set the selected core to 0. If the core flips state then a current is induced in the sense wire and that current tells you the core was a Ƈ'. If there's no induced current, then the core was already set to Ɔ'.

There's an obvious problem with this. Whenever you read a core, its state always ends up as Ɔ'. In other words, reading is destructive. With core memory, once you've read the state of the memory you need to write it out again to preserve the contents. Quick it ain't.

Rings of ferrite (a 'toroidal' shape, if you prefer) work best because their magnetic fields are self-contained and have no poles. You can pack them reasonably close together without them interfering with each other too much. To reduce any clash of magnetic fields even further, neighbouring cores are angled in different directions.

This technology has one advantage that stems from the use of magnetism rather than electricity to hold the state of each bit — the memory remains even after all power is switched off. It's non-volatile, rather like flash memory.

Thing of beauty

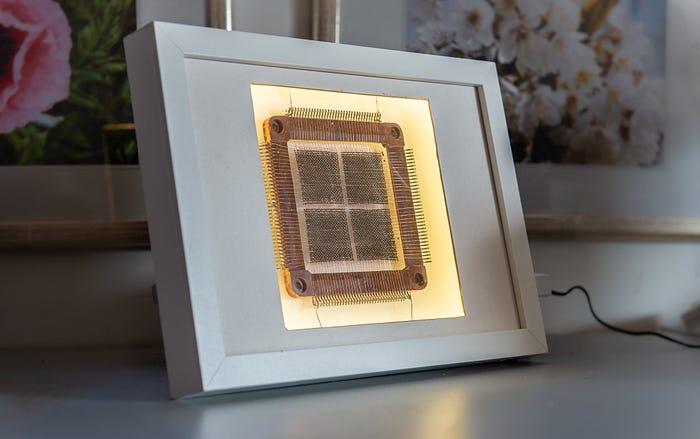

When the core memory turned up in the post my first impression was of something hand-crafted — not at all the kind of inscrutable and bland packaging of modern chips. It's a thing of beauty.

In fact, it's such a fascinating object that my More Significant Other was moved to admit that she'd like it to live, suitably framed, in the living room. That's never happened with any other piece of computer technology.

But first, I needed to grab some pictures. So I took myself off to my tiny studio. At one point the MSO called to ask me what I was doing. "I'm photographing my memory," I replied, truthfully.

Steve Mansfield-Devine is a freelance writer and photographer. You can find photography portfolio at Zolachrome, buy his books and e-books, or follow him on Bluesky or Mastodon.

You can also buy Steve a coffee. He'd like that.