RETROCOMPUTING

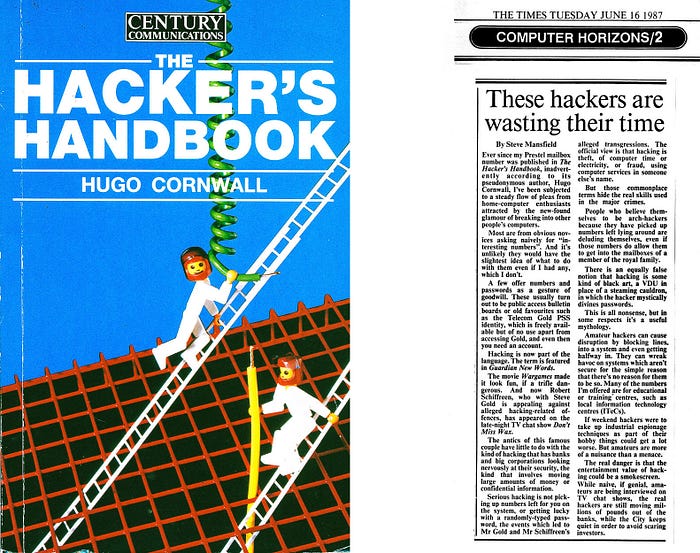

On its publication in 1985, The Hacker's Handbook was a sensation. It seemed to legitimise an activity that many of us had been engaged in for a while — the (mostly) innocent exploration of online computer systems.

This year the book celebrated its 40th birthday and the world has changed out of all recognition. Hacking has lost its innocence.

We now live in an age of connectedness. Our phones, our TVs and even our fridges are just nodes on a giant network. Email and texting are intrinsic parts of our lives. All of human knowledge appears to be just a quick search away. And to most people the term 'hacker' conjures a sociopathic criminal infecting hospitals with ransomware, a scammer after your life savings or evil state-sponsored cyber-spies stealing a nation's secrets.

It wasn't always thus.

The good old days

Back in the 1970s and early 1980s, a computer was a relatively rare sight in people's homes. And most of them were isolated machines. That would change quickly, of course, but before the likes of CompuServe and AOL made going online seem mundane, connecting with remote computers with the aid of a modem was an arcane business. Even legitimate activities, such as logging on to Prestel to get the weather or Telecom Gold to pick up email, seemed like tapping into the future.

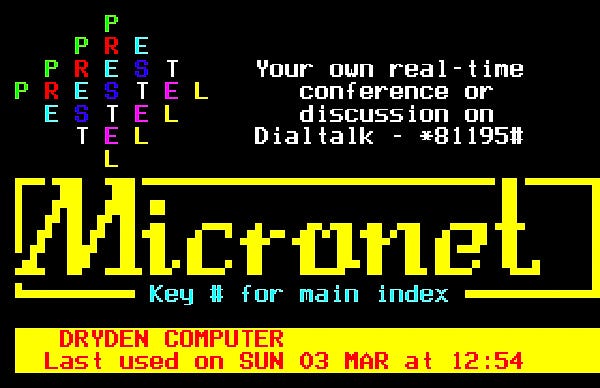

Prestel was an online service, of which Micronet 800 was a sub-section dedicated to microcomputer users. This proto-web allowed you to get information about stuff like the weather and share prices — somewhat like Ceefax and other TV information channels with which it shared Viewdata protocols and graphics. But it was also interactive. You could, for example, send email messages to other Prestel users.

I got online in 1983 thanks to a Prism VTX 5000 modem which was designed to sit under my Sinclair Spectrum. It was purely a Viewdata modem, operating at a fixed 1200/75 split baud rate, which was fine for logging into Prestel but highly limiting beyond that. I quickly outgrew it, and the same went for the Spectrum.

Once I'd upgraded to a BBC Micro and a modem capable of 300 and 1200 baud, as well as Viewdata's split rate, there was no stopping me. Well, nothing other than my phone bill.

The other essential piece of equipment was a push-button phone with a redial feature — an exotic item in the UK of the early 1980s. It cost me a week's wages but was worth every penny. And that's because my principal online activity consisted of dialling into bulletin board systems (BBSs). Most of these were run by enthusiasts who each had a single phone line. More often than not the line would be engaged and you'd have to redial. And redial. And redial. It was wearying stuff.

Interesting numbers

My favourite BBS had a forum, Hacker's Club, dedicated to people who enjoyed exploring computer networks and systems. That's what the term 'hacker' meant back then, although it was already acquiring an implication of naughtiness. Stories abounded of hackers perpetrating huge financial crimes or threatening the safety of nations. Nearly every one of these stories was an urban myth.

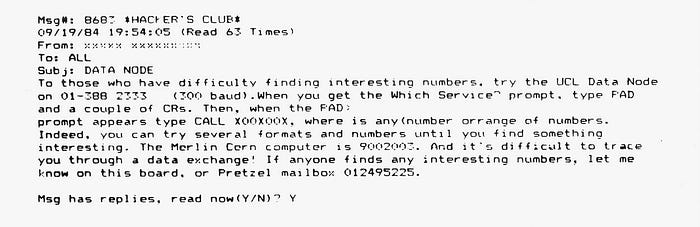

On the BBS, we would share 'interesting numbers', which meant the phone numbers of computer modems for systems not intended for the great unwashed public.

I particularly enjoyed dialling into university mainframes and mini-computers. These were insecure by design. Their operators wanted their capabilities to be easily accessible to students. And if the occasional non-student dialled in from time to time and had a look around … well, that was largely tolerated. Occasionally, an irate system manager would ping me a message saying 'who are you?' and then kick me off the line when I couldn't come up with a convincing answer fast enough.

Usually, however, I'd simply try running some of the programs written by students and read a few documents. I was careful not to do anything disruptive or destructive.

Some of those universities operated unsecured PADs (Packet Assembler/Disassemblers) that provided access to the X.25 packet switched system. This was a network with some similarities to today's TCP/IP networks that form the internet. Once logged into a PAD, you could hop from one site to another, travelling around the world.

Age of innocence

But back to the book. The author's name, Hugo Cornwall, was a pseudonym — for Peter Sommer, who went on to a very successful career as a security consultant. One of the other people who contributed to the book, editing and co-writing later editions, was my old pal Steve Gold, sadly no longer with us. Right up until shortly before his death, Steve and I spent many a happy hour chatting about the golden days of hacking when it all seemed such an innocent pastime.

Actually, it was innocent. Literally. The prosecution of Steve and Robert Schifreen for 'hacking' the Prestel online system revealed that, at the time, UK law was rather lacking when it came to dealing with computer-related activities. With no legislation specifically outlawing this kind of technological trespassing, the best the prosecutors could come up with was accusing the two men of "uttering a forgery". They were ultimately acquitted and this led directly to the creation of the Computer Misuse Act 1990.

Personal effects

There were six editions of the book all told — I have the first two. All, as far as I know, contain one small piece of content that affected me personally.

In several places, 'Hugo' had reproduced messages from the Hacker's Club forum. Conscientiously, all the names were replaced with rows of Xs (although with one X per character it's still easy for me to work out which messages were written by Steve Gold and which by me). Alas, in one of my messages I'd stupidly mentioned my Prestel address.

In the message I say: "To those who have difficulty finding interesting numbers, try the UCL Data Node on 01–388 2333 (300 baud)." I provided some advice on negotiating the system, including how to reach the Merlin computer at CERN. (That's how the computer identified itself, although Merlin was actually the name of a software system for event visualisation and analysis in experimental particle physics.)

So what's the problem?

At the time 'Hugo' grabbed that printout for the book, my message had been read 63 times. The Hacker's Handbook was destined to be read by a lot more people than that.

What's more, on Prestel, your address was your nine-digit Prestel ID. The wrinkle was that, in the early days at least, the operators of Prestel thought they'd make life simple by making your ID the same as your telephone number.

Don't call me

Not long after the publication of the book I started getting phone calls from wannabe hackers. Being geeks, these calls invariably happened in the small hours of the morning. That's because they were taking advantage of off-peak phone charges and also because, well, they were geeks.

And so, at 2am or 3am, I'd be woken by the phone, which in those days was fitted with a loud bell that couldn't be turned off and was unfortunately positioned at my bedside. A voice which, with no introduction and in hushed, conspiratorial tones would say: "I was just wondering if you have any interesting numbers."

I was lucky in one way. British Telecom had just switched from its practice of wiring in phone handsets directly to providing jack plugs. So I got into the habit of unplugging the phone each night. But sometimes I forgot, and the calls would come.

That conspiratorial tone of voice eventually clued me in. Hackers are nothing if not paranoid. When the caller asked the inevitable question about numbers, I'd reply: "I don't think it's a good idea to discuss this on an open phone line, do you?" That always got rid of them.

This happened so much that I wrote a piece about it for The Times — two years later! I must have penned this just before I met Steve because it's not very flattering about him. We had a laugh about that later. But my main beef was with these idiot callers. What I was trying to describe in the piece — although the term had not yet been coined — was the script kiddie.

Because those callers are still with us — idiots looking for bragging rights or opportunities for vandalism but without the intelligence, patience or commitment to learn their trade. You'll find script kiddies on any open hacking forum looking for easy, ready-made ways of creating mayhem.

Serious business

Most of my journalism work covered IT and it was inevitable that I would gravitate back towards hacking.

I spent the last 15 years of my working life (to be clear, I'm retired, not dead) as editor of two professional journals covering cyber-security. At the start of that period, cyber attacks already represented a major threat to individuals, organisations and even entire countries. I reported on the emergence of 'cybercrime-as-a-service' and the weaponisation of computer vulnerabilities as part of the concept of hybrid warfare.

And the average person's understanding of hackers today is not far off the truth. The Russian 'bears' — most notably Fancy Bear (operated by the GRU military intelligence service) and Cozy Bear (linked to the SVR and possibly FSB intelligence services) — have proven to be effective and aggressive weapons in Vladimir Putin's attacks on the West.

Every day, cybercrime gangs, many of them acting with impunity from Russian soil, attack people and organisations.

For years, elements of China's People's Liberation Army have been engaged in widespread and highly effective theft of western intellectual property — famously stealing many of the F-35 jet fighter's secrets. And the North Korean regime runs crypto-scams and ransomware campaigns, and performs massive cryto heists as a way of accruing foreign currency.

These are just some random examples. Cyber-attacks are a global problem and both criminal and state-sponsored threat actors operate in every country.

In the meantime, many nations — including the UK, US and most of Europe — now have offensive cyber units within their military force structure.

With a longing sigh

And so it's with no small degree of nostalgia and longing for a simpler time that I leaf through my old copies of the Hacker's Handbook.

There's not much in it that remains relevant to computer communications today. Changes in technology have left it behind. Yes, serial comms are still employed, and the concepts of data length, parity and stop bits remain in use, but mainly in specialist applications such as embedded computing and the Internet of Things. And the X.25 network is still out there, but again in more specialised applications. If your interest is in hacking, then the Hacker's Handbook won't be of much help.

Yet it remains fascinating from an historical perspective, and it encapsulates that spirit of eager curiosity that once defined the true hacker.

Steve Mansfield-Devine is a freelance writer, tech journalist and photographer. You can find photography portfolio at Zolachrome, buy his books and e-books, or follow him on Bluesky or Mastodon.

You can also buy Steve a coffee. He'd like that.