PROGRAMMING

Ever had the desire to go back in time? And not to witness the Wright Brothers' first flight, the crowning of Henry VIII or the building of Stonehenge. Just perhaps an hour back, to the time before you made that stupid coding mistake that has screwed up your program and which you can't fix because you can't remember what you did.

Well, you can. You can do a lot of other things, too, if you use version control when programming.

Rolling back

Version control — which pretty much means Git these days — is a way of saving your work at key steps, so that you can roll back to earlier versions if necessary. You can also maintain separate 'branches' of your code — effectively parallel versions. And, if you want to go that far, it's a great way of working on code bases with others.

For a long time, version control was the preserve of professional coders working in teams. It was difficult to set up and maintain. It was complicated. It offered few benefits for those who weren't extremely serious about their programming — and getting paid for it.

But no longer. Git is easy to install, simple to use and has advantages even for the lone, self-taught hobbyist programmer, like me.

Really. You should try it.

I'm not here to tell you how to install Git or use it. The web is awash with tutorials. My goal is to convince you that it's a valuable tool. And the motivation for writing this article is something I read recently on a forum dedicated to fans of a particular vintage microprocessor.

A member mentioned software that they'd developed and that it was available via their GitHub account. And the rather sniffy response from another member was: "I don't do GitHub."

And I thought, why on earth would you say something like that? At its most basic level of functionality, GitHub is just a website where you can go, look at and (if you are so moved) download other people's code. What possible objection could you have to that?

And then it occurred to me that perhaps this person was intimidated by the whole concept of Git (and perhaps version control in general) and had just written it off as either too complex or not worth his time.

But the fact is, Git is whatever you want it to be. You can use it a little or a lot. You don't have to be tied into online services such as GitHub or GitLab. You can employ it locally on your one machine or, like me, set up your own GitHub-like server on your home network, safe behind your firewall.

Keeping track

Git keeps track of all the changes you make to code. By logging the changes, it knows how to roll back to a previous state.

On too many occasions I've decided to 'improve' a program, have spent some considerable time making amendments and adding features, only to get to the point where I realise:

- It doesn't work.

- It's never going to work.

- I've forgotten what changes and additions I made.

You could solve this problem by always making a backup of the current state of the code before embarking on modifications. But such a manual approach is clumsy, easy to forget and leaves your hard drive clogged with old files. And I've lost count of how many times I've opened a source code file to make 'one small change' — so no backup necessary — and found myself, an hour later, staring at a program that has grown by 25% or 50% and no longer works.

Pushing and branching

Git has many, many features, most of which we don't need to discuss here and many of which I'll never use. However, for me, there are three key concepts that I find invaluable — repos, pushing and branching.

Like I mentioned, Git keeps track of your changes and you could just keep that information on your machine in case of dire emergencies. But keeping your code in a repository ('repo') makes a lot more sense.

A repo is essentially a remote store for your files. You can share it publicly, if you want, or keep it private. You can download the whole project to a new machine simply by typing git clone <url> on the command line, and later update to the latest version of the code with a similarly simple command.

But changed files don't get copied to the repo automatically. You decide when the new versions are uploaded to the repo by doing a 'push'. Each time you do this, you add a label which, if you choose suitably descriptive text, will enable you to roll back to a specific point in time if you need to.

And then there's branching. You can have multiple timelines for your code so that you can, for example, keep working code safe in one branch while trying out new features in another. I'll talk more about this in a moment.

Taking risks

Using Git allows you to both take and eliminate risks. Let me explain what I mean.

First, you can take risks on refactoring code or trying out new ideas knowing that you can always easily recover from stupid errors or failed experiments. It really frees you up to try approaches to coding that may be outside your comfort zone. That's the 'taking risks' side of the equation.

As for reducing risks, if you decide to use a remote repository such as GitHub or GitLab, you automatically have offsite backups of your code.

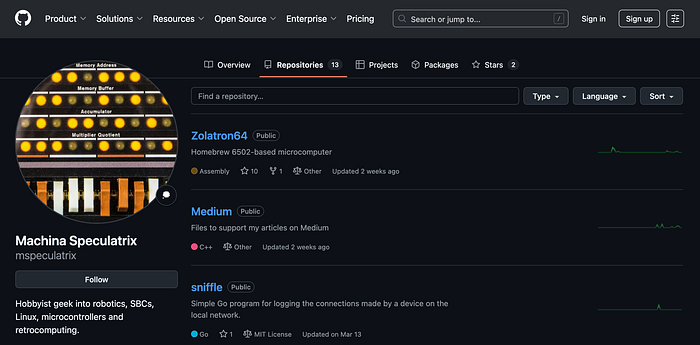

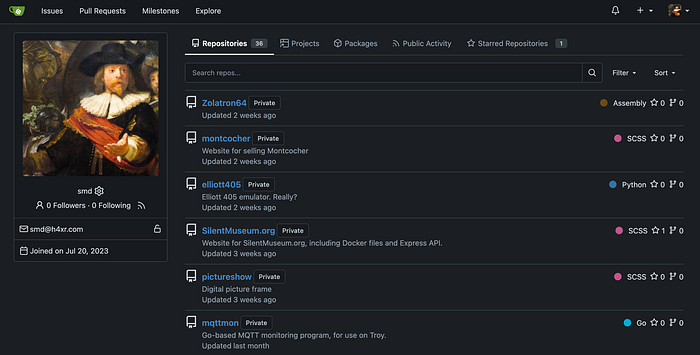

If you prefer to keep things in-house but, say, want access to the code from multiple computers, you can always set up your own hub. I use Gitea running in a Docker container on my NAS. It was remarkably easy to get running. Most of my projects have a repo on the Gitea instance, some are on GitHub and others — such as my Zolatron homebrew computer project — are on both (yes, you can push code to multiple repos).

Another advantage of a Git repo is that it's a centrally managed place to put everything relating to your project. In the Zolatron repo, for example, I include notes, PDFs of data sheets, diagrams, schematic images and Gerber files for PCBs. Everything is in one place and accessible from multiple computers.

And using a repo positively encourages documentation which, as we all know, is a good thing. At the very least, you'll likely create a README.md file in which you can keep notes on the project.

Using Git

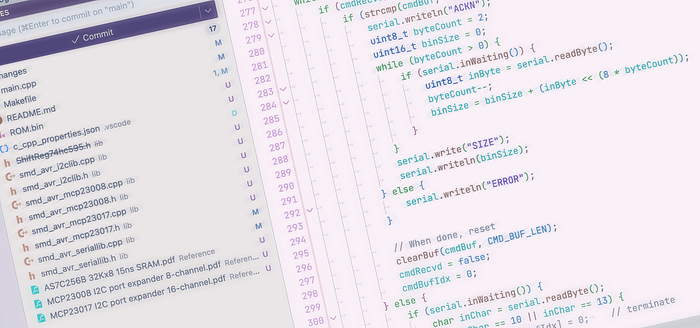

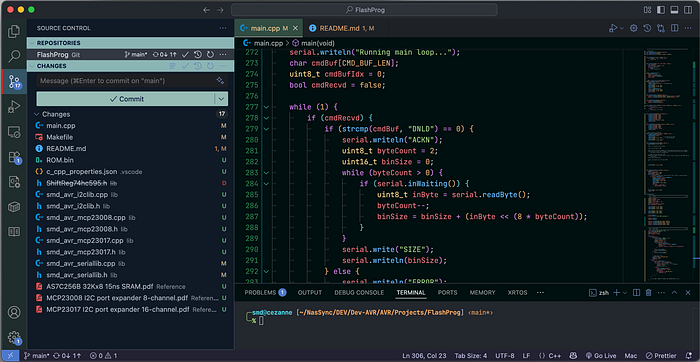

You can use Git from the command line. I hardly ever do that. The reason is that Git functionality is often built into coding editors and integrated development environments (IDEs).

My editor of choice is Microsoft's VS Code, which I use on both Macs and Linux machines. Pushing changed files to a repo is a matter of a few clicks. The same goes for switching between and merging branches. On the Macs, I also use Xcode which is nearly as simple in its Git functionality.

As to how I use Git, it goes something like this.

I set up a new repo on Gitea for any coding project that isn't completely trivial. If it's a project I think would be useful to share with the world (such as the one I created to support this publication, or the one for my AVR microcontroller-related articles) I'll set up the repo on GitHub. Either way, the initial branch is called main (which is the default these days).

I push files to the repo whenever I feel I've made significant additions or changes. I don't do it every programming session — that would create too many restore points. This is down to gut feeling, but I basically ask myself, 'have I made sufficient changes that I wouldn't want to go through all that again?'.

When I have a basic working version of the code, I push everything to the main branch and then create a new branch, called dev. (You can name branches whatever you want.) All new work is carried out on the dev branch until I'm confident that the code is good and functional. I will then merge the dev branch into the main branch. The main branch then has all the new functionality but it's also a version of the code that actually works. Before doing any further work, I'll switch back to dev.

One thing I find myself doing quite often is, while working in the dev branch, and finding that changes I've made have b0rked something, I'll simply hop on to the Gitea or GitHub web page and take a look at the earlier code from the main branch. It's a quick-and-easy way of seeing where things might have gone wrong without actually switching branches in my coding environment.

Staying safe

If you decide to share your repos online, it's important to be aware of exactly what you're sharing.

As a rule, you should never hard-code credentials into your software. Passwords, authentication tokens, SSH keys are among the items you need to keep private. That principle applies regardless of whether you use Git or share the code.

Alas, it's all too easy to make a slip. Perhaps you're coding a project that you think only you will use, in the privacy of your own home. But then, months later, when you're vague about exactly what is in the code, you decide to share your creation with the world — complete with that AWS access token you'd forgotten. It happens all the time.

'GitHub dorks' are now a thing. This is in the tradition of Google dorks, in which hackers use search engines to find vulnerable systems. With GitHub dorks, ne'er-do-wells use GitHub's search facilities to find code uploads that leak secrets.

It boils down to this: never put passwords or other sensitive items directly in your source code. Ever. If you get into that mindset, you'll be a lot safer.

Depending on what you're coding and how, one solution is to put credentials in your computer's environment variables. Corey Schafer has an excellent video on just this for languages such as Python. That link is tothe Mac and Linux version, but he also has a version for Windows. (This is a channel that's well worth supporting, by the way.)

Another approach is to put credentials and other sensitive information into a file that is not included in the repo. Git allows you to designate files that it will simply ignore. The list is held in a file called, appropriately enough, .gitignore. This lives in the same directory as your code, so is specific to that project.

All of my .gitignore files contain the entry:

__*This means that any file starting with a double underscore will be entirely ignored by Git — it won't be tracked and it won't be uploaded to the repo.

Let's say I have an ESP32 project in which I need to provide login credentials for my wifi. I'll create a file called __wifi_creds.h with some defines:

#define WIFI_SSID "My_Home_AP"

#define WIFI_PASSWORD "topsecret"And then I just include this like any other header file and use the macro names wherever I need the SSID and password.

#include "__wifi_creds.h>"Then I will include an example credentials file in the repo, containing dummy values and a note on how users should amend the file to suit their own needs.

Note that this solution is simply a way of avoiding accidentally uploading credentials in plain text on Github. Somewhere along the line, these credentials will be included in the compiled binaries. So it's also a good idea to use .gitignore to exclude binary and intermediate bytecode files too. For C or C++ projects, the .gitgnore includes: *.o. For Python code, it includes: __pycache__.

More features

There's so much more to Git that I haven't examined here. I've deliberately avoided getting into the weeds of pull requests etc, mainly because these are features I don't use, although they do open up the exciting potential for collaborating with others.

But even using Git in a very basic way has saved my life many times.

Steve Mansfield-Devine is a freelance writer, tech journalist and photographer. You can find photography portfolio at Zolachrome, buy his books and e-books, or follow him on Bluesky or Mastodon.

You can also buy Steve a coffee. He'd like that.