We might have figured out the secret sauce of Gemini 1.5.

Gemini 1.5 is Google's new Large Language Model (LLM) that offers a performance — not to be confused with alignment — never seen before, beating the previous state-of-the-art by 50 times.

And that secret might be Ring Attention, a discovery by researchers at Berkeley University as a new way of running LLMs that enables efficient distribution to maximize their raw power and reach new, unreached heights.

In fact, this breakthrough might be the key to unlocking the power of the Transformer, the architecture behind Gemini and ChatGPT, proving once again that 2024 will be even crazier than 2023.

This insight and others have mostly been previously shared in my weekly newsletter, TheTechOasis.

If you want to be up-to-date with the frenetic world of AI while also feeling inspired to take action or, at the very least, to be well-prepared for the future ahead of us, this is for you.

🏝Subscribe below🏝

What's an LLM at its Core?

To fully understand how revolutionary Ring Attention is, we need to comprehend how Gemini or ChatGPT work.

Thus, first and foremost, we must ask, what happens when I send them a text message?

When words become numbers

You may have wondered how LLMs understand what they are told. For instance, how does ChatGPT know that the next word to the sequence "the Siberian Husky is a type of…" is "dog"?

For starters, it 'breaks up' the sequence into tokens, that is, the different words and subwords that the model knows as part of its vocabulary.

For example, using the previous sequence, that could be ['the', 'Siber', 'ian', 'Husky', 'is', 'a', 'type', 'of', 'dog'].

This essentially breaks the sequence into parts that the model recognizes and thus can process.

As you can see, those parts aren't always words, they can also be subwords, which is actually more common.

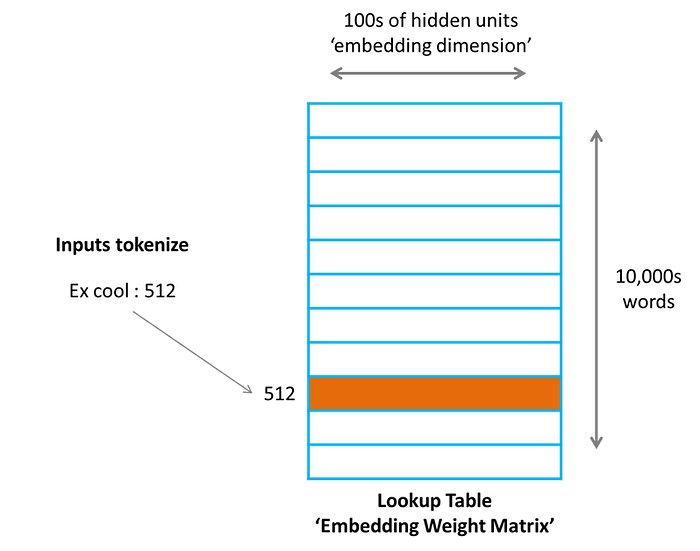

Next, it applies a transformation we describe as 'embedding' where it turns each of these tokens first into an integer, and that integer is then used to locate the embedding for that token from the embedding lookup matrix.

These embeddings could be calculated 'on the go' (referred to as 'online' by the community) using an embedding neural network, but in the case of LLMs, we have realized that we can simply learn the embedding for each word/subword in the LLM's vocabulary as part of the training process and simply 'look them up' during inference (runtime) using a look-up matrix.

But why do we do this? Well, for two reasons:

- It's a necessity, as computers always work with numbers.

- To make concepts measurable. By turning words into vectors we can measure their distances. This helps the model identify similar concepts, such as 'cat' and 'dog', using mathematics. This is referred to by OpenAI as 'relatedness'.

Importantly, embeddings capture the semantic meaning of the original text token.

In other words, you can think of embeddings as yet another way of representing concepts, like representing 'dog' or 'cat', but in another language such as Spanish, but this time, instead of 'perro' and 'gato' this new language is numerical, to make it understandable for machines.

Thus, even though they are a set of numbers, they 'capture' the meaning of the original word, which means they are not randomly defined and should be similar when describing similar concepts.

For instance, 'dog' might be represented as [3, -0.2, 4, -3]. And 'cat', as it shares several attributes with 'dog', might be something similar like [3.2, -0.19, 4.1, -2.98].

Now that we have our sequence turned into a set of embeddings, it's time to send them to the model.

And here is where the magic happens.

Self-attention is the key

If we think about language and analyze how it works, we soon realize one thing: words have meaning not only by themselves but also by the context of their surrounding words.

For instance, "The river bank" and "the money bank" share the word 'bank', but with different meanings in both cases.

In other words, to figure out what 'bank' is at any given time, we need to pay attention to the other words in the sequence. Therefore, the self-attention mechanism is how machines do precisely this.

But, how does it work? Seems complicated but it's not. Bear with me.

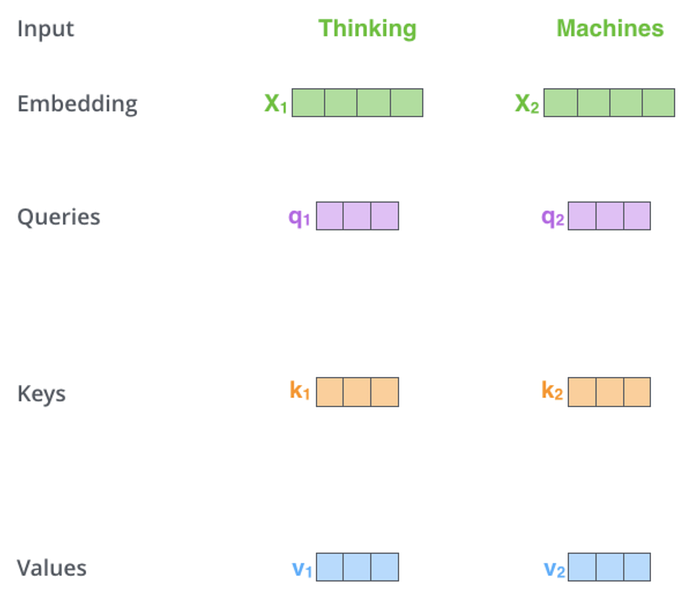

To start, each of the embeddings of the sequence is projected (transformed) into three vectors, Q, K, and V.

But what are these vectors? Put simply, they are the way the embeddings representing the original words will communicate with each other, and each of them tell a particular thing about the word.

- The Query vector is the word's way of saying 'This is what I am looking for'

- The Key vector is the word's way of saying 'This is what I have to offer'

- And the Value vector is the word's way of saying 'If you want to pay attention to me, this is what I have to offer back to you'

This way, the words can communicate by multiplying their Query vector (Q) with the Key vectors (K) of the other words.

Circling back to the previous example, this way the word 'bank' realizes whether it's a river bank or a financial institution after interacting with 'river' and 'money' respectively.

Looking back at the principle of relatedness, if the query vector (Q) of one word is similar to the Key vector (K) of another word, the result of multiplying both vectors will be high, indicating that they should be paying attention to each other.

For instance, nouns and adjectives related to those nouns will display a high attention value, as will adverbs and related verbs.

Then, using the Value vectors (V), each word embedding gets updated with the information of its surroundings.

The actual calculation will look like something such as this:

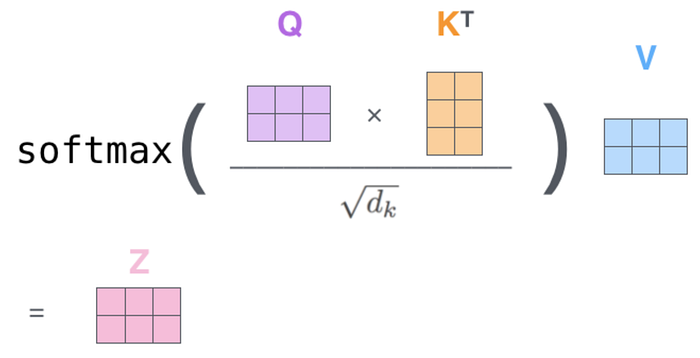

Then, once we have the information that other words want to provide, we sum them up to obtain vector 'Z', the new updated version of the word embedding, but now including surrounding context.

The final calculation includes four technical aspects I purposely avoid for the sake of simplicity:

1. we need to divide by the square root of the dimension of the Q/K/V vectors for more stable learning.

2. we apply a softmax (a mathematical operation that turns a list of numbers into a list of probabilities that add up to 1) so that each word gets updated with the information from other words in a weighted manner.

3. this self-attention process is done multiple times. This is referred to as 'multi-head attention' meaning that each 'head' executes the aforementioned process once for every token. Consequently, each head specializes in a certain text pattern.

4. Additionally, a standard Transformer has multiple self-attention layers. Thus, this process is not only performed for various heads, but across multiple layers too.

Bottom line, the self-attention mechanism induces the model to discover the patterns and relationships between words for any given sequence.

It's important to note that models like ChatGPT and Gemini are autoregressive decoders. In layman's terms, words can only pay attention to words that appear previously in the sequence.

Next, we now move on to the feedforward layers, which are equally as important.

The importance of non-linearity

With the word embeddings freshly updated with the information provided by the other words in the sequence, we send them into the feedforward layers (FFNs).

I won't get into as much detail as I did with self-attention, but to simply mention that this layer updates all the embeddings equally.

Technical intution: Fundamentally, this layer is included to apply non-linearity to the whole process.

By doing so, the Transformer can then learn new complex patterns in the data that aren't necessarily linear (basically almost any function in the real world isn't linear, and that includes modeling language).

Long story short, the key point to extract from FFNs is that, although a fundamental part of the process, they severely increase the number of computations and also the memory requirements.

Moving forward, there's a key concept we haven't touched on, and that's the fact that the complete sequence of embeddings is inserted into the LLM at the same time.

Wait, what?

Wait… isn't language sequential?

Even though words follow a sequence and order, models like ChatGPT and Gemini process all words at the same time, which means that these operations we just described are performed over the complete sequence of text simultaneously.

The reason for this is that the attention mechanism is fully parallelizable, as the way the different words talk is not dependent on each other.

Hence, the process is highly parallelizable, making the use of Graphics Processing Units, or GPUs, mandatory. And to say GPUs are important these days is a massive understatement.

To convey its importance, here's a crazy stat for you:

NVIDIA, the company that owns 90+ market share of the GPU market has added, since the beginning of 2024, the entire value of Tesla to its valuation, more than 700 billion dollars.

But with Ring Attention, the GPU paradigm might change completely.

The Great Memory Problem

As far as Transformers are great at modeling data, they have a huge issue: They are extremely inefficient, especially concerning memory management, forcing companies to oversize their data centers.

But why?

The memory bottleneck

Looking back at the process we described earlier, performing the attention mechanism and feedforward networks is a massive endeavor considering the sheer amount of parameters these models have today, in some cases reaching over a trillion parameters per model.

They undoubtedly require a high number of computations, but the real bottleneck comes from the huge amounts of memory they require.

For starters, the entire model resides in memory (mostly on the High-bandwidth Memory (HBM) memory layer in the case of GPUs).

The reason for this is that the model's parameters are queried for every single prediction, requiring the entire model to be easily accessible.

Therefore, assuming a model has a trillion parameters at a float16 precision (meaning that each parameter occupies 16 bits (or 2 bytes) in memory) you require 2000 GB of HBM memory storage, or 2 TB… just to host the model during inference.

Alas, considering state-of-the-art GPUs have a maximum of 80 GB of HBM, that means that you need 25 of these just to store the file.

But that's not all.

The attention mechanism we described earlier becomes extremely redundant in its computations as words are predicted over the same sequence.

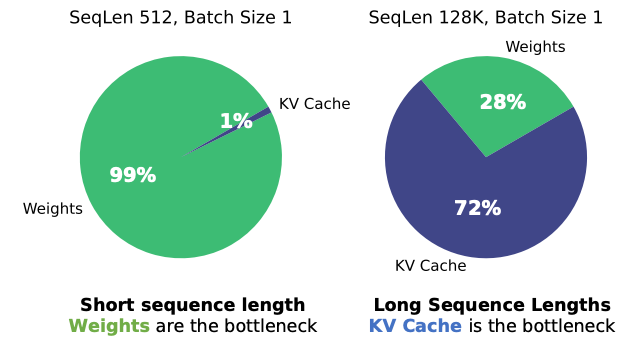

This means that we can — and need to — store the Key and Value activations we described earlier to avoid having to recompute them, something we know as the KV Cache.

For example, if you have the text sequence "The capital of England is…" and the model predicts "London", once the model predicts the following word, the attention scores between the previous words in the sequence won't change (as they remain as part of the sequence) thus not requiring to be recalculated.

However, the issue is that, for long sequences, the KV Cache, literally, explodes in size, to the point that this problem has historically prevented LLM engineers from scaling their models to handle larger text sequences.

The memory issue is so relevant that it completely overtakes the whole process, meaning that LLMs, in inference (execution time) are 'memory bound', meaning that GPUs saturate on memory before they saturate their compute accelerators, meaning that GPUs are often 'idle' computationally speaking.

But, suddenly, Gemini 1.5 has taken the previous max sequence length milestone, set by Claude 2 with 200,000 tokens, and pushed it up to 50 times more to 10 million tokens, or 7.5 million words simultaneously.

Outrageous.

And although Google hasn't confirmed it, we might know how they did it.

Transformers and The Fellowship of the Ring

Ring Attention proposes a new way of distributing the computation of Transformers across GPUs.

From batch to sequence

As we described earlier, the Transformer architecture is very inefficient in terms of memory use because they don't compress context, meaning that they have to 'see' the entire sequence over and over again to predict each new word.

Imagine you had to reread all the previous pages in a book for every new word you want to read.

That's how Transformers like ChatGPT or Gemini read.

Consequently, for each text sequence, we must store in the GPU's HBM memory the attention activations (the KV cache), which in turn grow in size for every word prediction.

As mentioned, as sequences grow larger the KV cache becomes the main memory bottleneck, forcing LLM providers to limit the maximum length of the sequence you can send the model at any given time, otherwise known as the context window.

And here is where RingAttention comes in to do a profound adaptation, as now, instead of dividing the batch, we are distributing the sequences.

The communication overlap

The key intuition behind Ring Attention's innovative approach is that for very long sequences, we break them into 'blocks' and send each block into a different GPU.

For example, if we have a very long sequence of 100,000 tokens and 10 GPUs, each GPU should receive on average 10,000 tokens of the sequence.

The reason why these works comes from the fact that, as we recall from earlier, Transformer architectures process all words in a sequence at once.

Technical insight: In the Transformer, to ensure that the model accounts for the order of the sequence, we include positional embeddings for each of the tokens, signaling the model in what position each word really is.

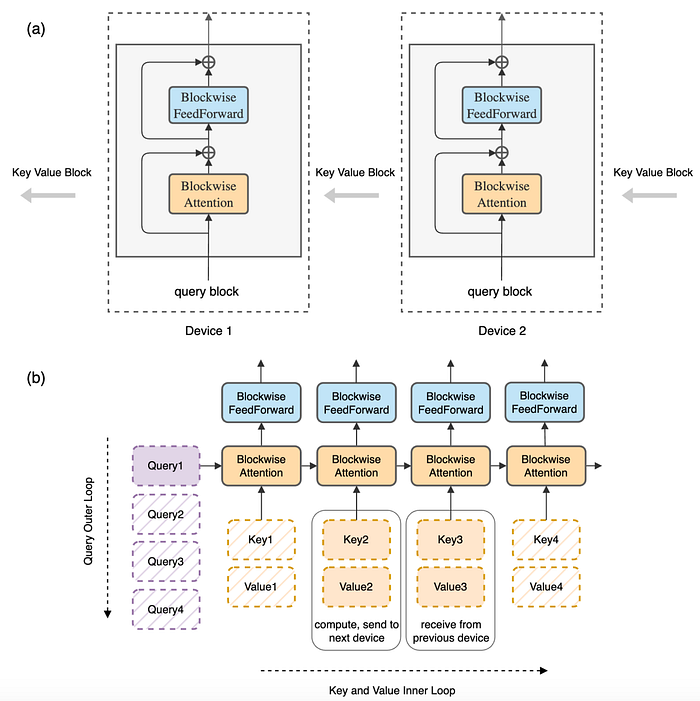

This takes us to the following image, where we can see Ring Attention's proposal for distributing compute:

To understand how these works, let's say we have the pangram "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog", and three GPUs.

The point of Ring Attention is to handle much longer sequences, this is just an illustrative example.

From that, we divide the sequence into three blocks of text, one per GPU, such as "The quick brown", "fox jumps over", and "the lazy dog". This block-wise processing implies the need for two loops:

- Outer loop. We assign the queries of each block to its specific host (GPU). In other words, the Q vectors of "The", "quick" and "brown" are assigned to the first GPU, and so on.

- Inner loop. On the other hand, each GPU will be in charge of computing self-attention over the queries of its assigned text block, as well as the feedforward computation for those tokens. In this case, the first GPU will perform self-attention over the three first tokens, "The", "quick", and "brown" and pass them also through the FFN layer.

However, we are missing something. If we recall the self-attention explanation, the query vector Q of a specific token needs to be multiplied with the key vectors (K) of every preceding token, without exception.

In other words, as the token "fox" is assigned to GPU number 2, it needs to see the K and V vectors of the first three tokens, "The", "quick", and "fox", assigned to the first GPU.

Therefore, for the attention mechanism to work, the GPUs must share the Key and Value vectors with each other, so that the multiplications can be done.

And here's where 'Ring' in Ring Attention starts to make sense.

In parallel to computing the self-attention mechanism and feedforward calculations of their respective block (inner loop), each GPU sends its K and V vectors to the next GPU while simultaneously receiving that information from the previous GPU, thereby generating a ring of sorts and creating the outer loop.

From this architecture, we derive a key principle.

As long as the GPU takes longer to process its block computations than sending/receiving the K and V vectors from the next/previous GPUs, this communication among GPUs does not cause a temporal overhead, as the GPU is occupied with its own calculations during transfer.

On the flip side, if the computation of the inner loop finishes before the transfer, the GPU has to wait for the K/V vectors from the previous GPU, creating a delay and defeating the purpose of this architecture all along.

In the paper, the team calculates the optimal block size so that this never happens.

But what is the main point of all this?

Lower memory, more length

The benefits of this approach are simple.

- Using this ring-based GPU distribution, we eliminate the per-GPU memory bottleneck we described earlier, where each GPU quickly saturated its 80 GB of memory with long sequences due to the sheer size of the KV cache.

- Additionally, the sequence length scales linearly to the GPU count, allowing it to, theoretically, increase to infinity.

In layman's terms, there's no limit to the sequence length that can be processed by the infrastructure as long as you have enough GPUs for it.

Thus, considering Google is literally drowning in cash, it's not hard to predict that using this method they can consistently scale the sequence length to unfathomable sizes, meaning that the 10 million token context window they announced could merely be the tip of the iceberg.

Bottom line, it's too soon to tell, but Ring Attention could be the milestone that takes us into a new age of AI.

A Last Note on Open-Source

It's certainly fascinating to see how researchers find new innovative ways to push the veil of ignorance back a little bit every day.

With Ring Attention, it seems that the industry is poised to witness an explosion in terms of context sizes, a crucial element in our path to handling much more complex data types like video or DNA.

However, Ring Attention also gives us much deeper insight into the importance that hardware has in the AI race and how it can determine who eventually wins this AI battle.

Sequence length is of utmost importance to a huge number of use cases, but it is completely conditioned on having enough capital and resources to run these long sequences over multiple GPUs.

The problem?

Only a few players can play that game today, and nothing points in a different direction.

In fact, it may only get worse.

On a final note, if you have enjoyed this article, I share similar thoughts in a more comprehensive and simplified manner for free on my LinkedIn.

Looking forward to connecting with you.